Essential Photography Books (1)

Contenido

Vice

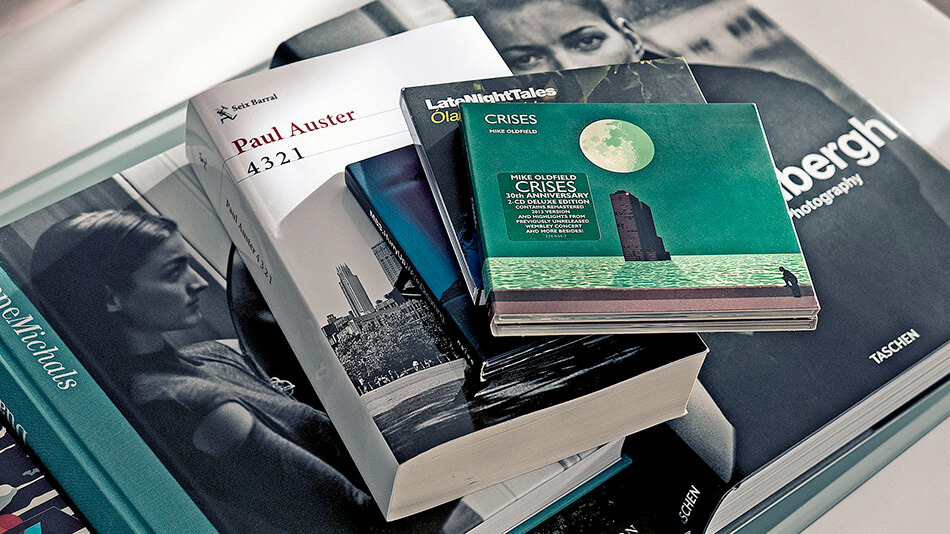

When I started to earn my living with my first photographic assignments, more than 25 years ago, I had two clear “vices”, music and photographic catalogues. At that time I had not yet set up my first studio and therefore was not yet aware of the meaning of “living to pay”. My only investments were records and books, and I wasn’t really planning to do much more either. I was happy with so little or… so much, depending on how you look at it. In fact, when I recall in my mind some passages from my previous youth, I can still clearly relive that almost orgasmic feeling of tearing off the plastic wrapping and discovering the interior design of a CD by Mike Oldfield or Wim Mertens, or the photographs in a catalogue by Duane Michals, Jan Saudek or Helmut Newton. Usually this scene used to take place on a train, back home, after liquidating much of my income in music shops and bookstores in the capital, and I think my ecstasy was more than evident because when I looked around it was not uncommon to come across someone watching me as if I was the same Gollum engrossed in his “treasure”.

These are pleasures that today have almost disappeared from my life, not because I cannot do the same as before, but because the sensations are not even remotely the same. With music, I subscribed some time ago to an online platform from which I access everything I want to listen to and that now it would be impossible for me to find published in any physical format. I have some quite particular musical tastes and if before it was already complicated for me to get some albums in cd format, now it is practically unfeasible outside the Internet channels. I could say that thanks to the online platforms I now “swim in abundance” in terms of my desired music, but without a doubt that same abundance, in which everything is available, has also made me lose the charm of that process that consisted of listening to a melody on the radio, becoming obsessed with it, searching for it, discovering the album and its author, getting on a train and kicking the music shops in the city until I found the object of desire and returning with the prize and the satisfaction of having successfully fulfilled a vital mission.

With the photography books and catalogues there is still quite a lot of that. The best way to enjoy them is still in their printed format, therefore, the pleasure of unpacking them and discovering their content still has some of that “craving”, although the times and oneself are different. I used to buy them in a specialized bookstore like the Railowsky Bookstore in Valencia (Spain), a veteran bookstore that is still active and now sells online. You could also spend a good afternoon in the book section of the FNAC, browsing through copies without rushing to choose, although their cultural vocation has been reduced quite a bit over the years. Now, without a doubt, the Internet is the best option to access those photography catalogues, either through the large online sales platforms, or through other more modest ones (bookstores, publishing houses…) where you can find some jewels originally published anywhere in the world, not to mention the second-hand market, where you can get some out-of-stock and well-preserved editions, although too often at exorbitant prices, especially if they are limited or special or are part of the exquisite group of legendary publications on photography.

The best way to learn to look for a photographer is to investigate the language of photography, which is not a straight line at all. The technique can be acquired and practiced with greater or lesser skill, but the look, as much as some have an innate gift, is exercised by discovering how the look of “the others” is.

The best way to learn to look for a photographer is to investigate the language of photography, which is not a straight line at all. The technique can be acquired and practiced with greater or lesser skill, but the look, as much as some have an innate gift, is exercised by discovering how the look of “the others” is, each with their own way of perceiving and understanding the photographic act and its processes. I have learned to look with the work of my true influences: Duane Michals, Chema Madoz, Helmut Newton, Erwin Olaf, etc… But also, thanks to their published catalogues I have learned a lot about how is the laborious process of selecting and transferring the photographic work of an author to a publishing project, with its formats, its design and layout and its quality of reproduction with respect to the original images… Some publications can become true works of art in themselves and a coveted piece for collectors.

So let’s go with a first selection of photographic catalogues. Some of them are still available, especially through online sales; others, unfortunately, have been discontinued, although due to their relevance they are worth a review, without ignoring some of those publications that have made exclusivity their main attraction, only to the supply of people with certain purchasing power (this is not my case, although it weighs on me…).

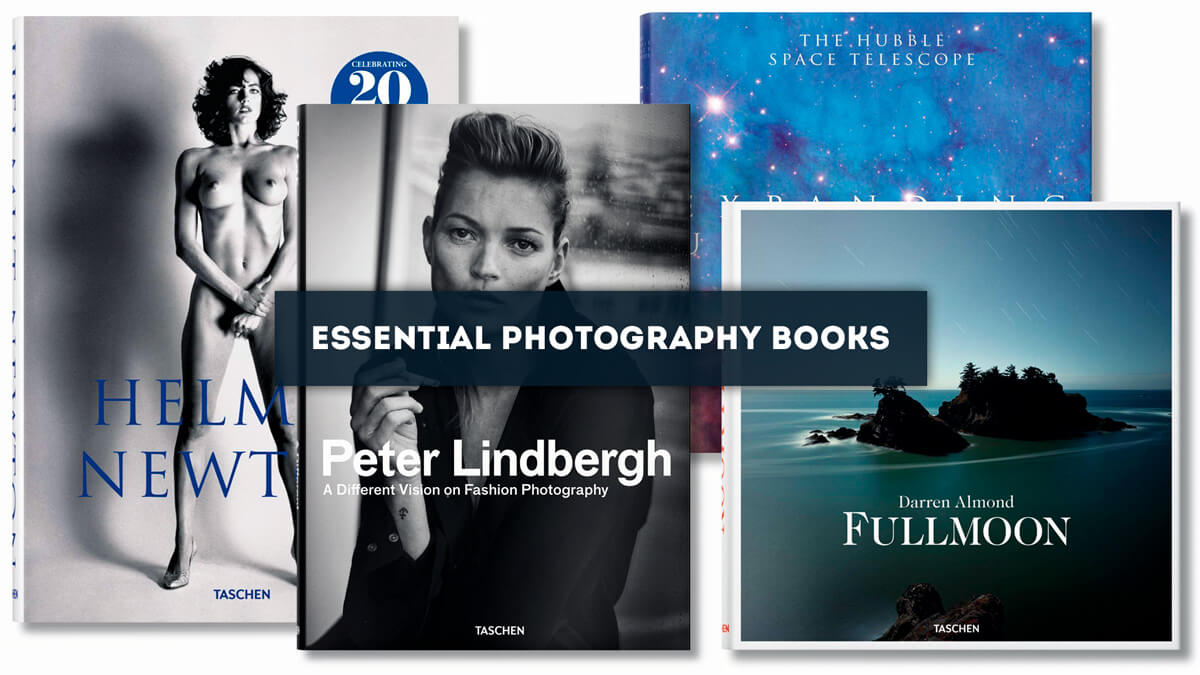

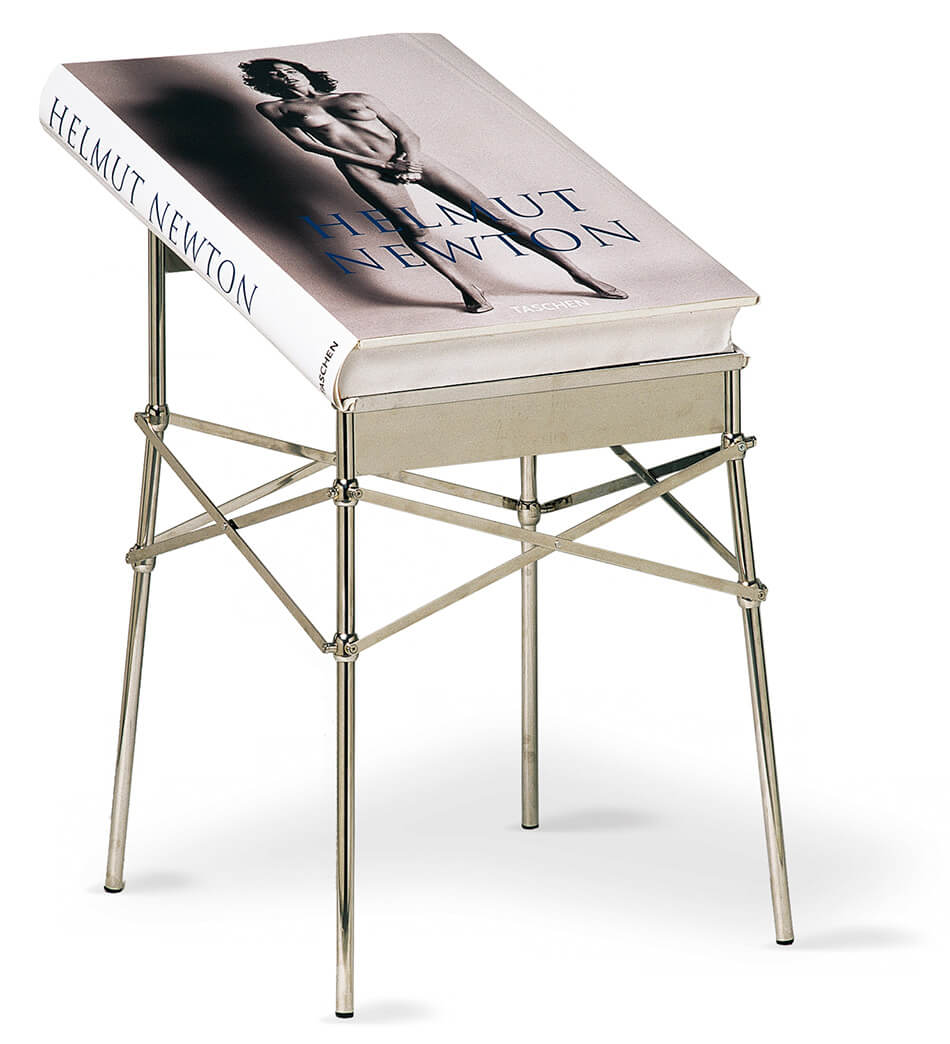

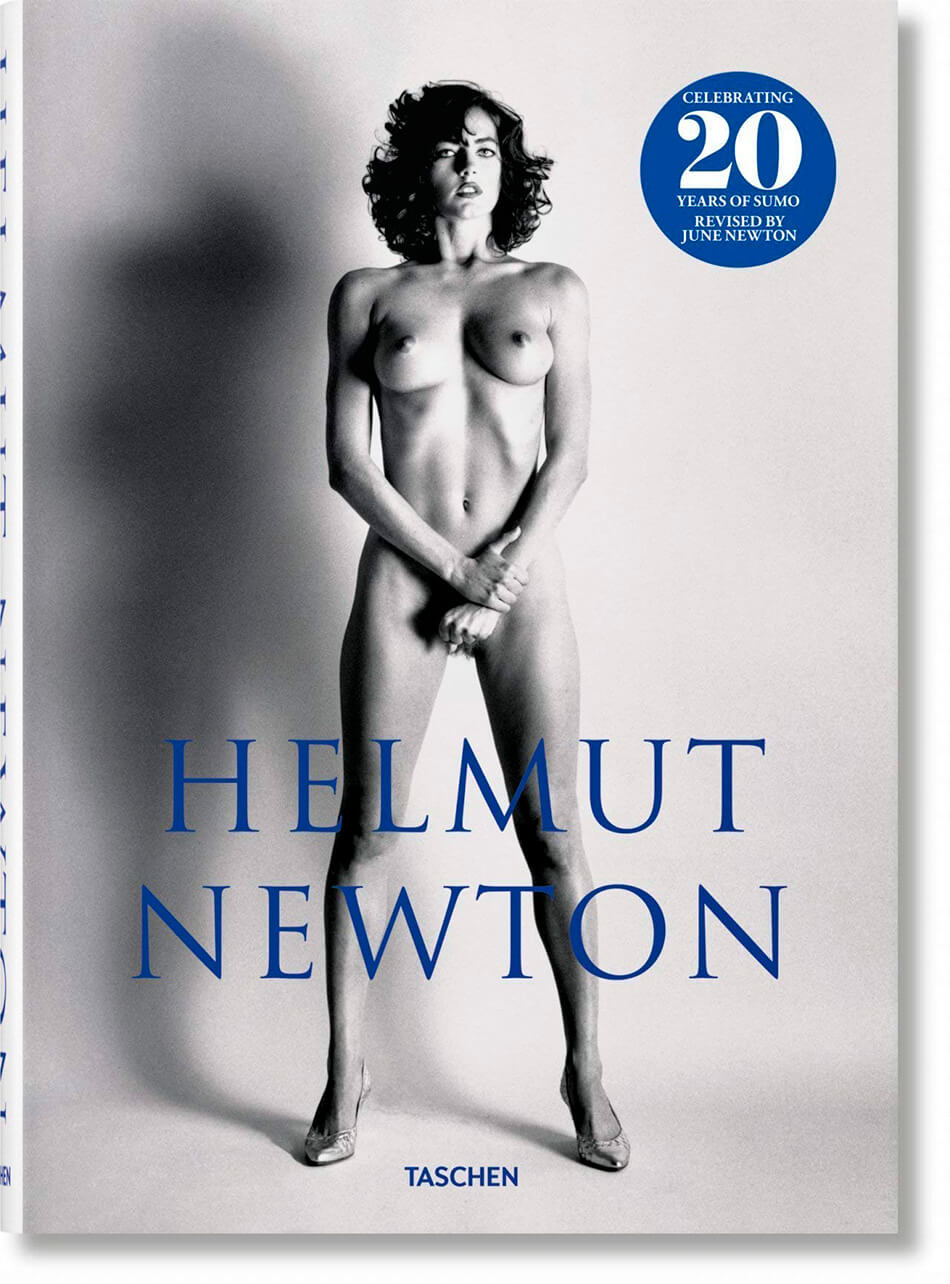

Helmut Newton’s Sumo

And we start with the titan of published catalogues. And the titan is not in the figurative sense because acquiring one of the 10,000 copies of Sumo published in its limited edition was, practically, like taking home a private exhibition bound, not only by the set of works, but above all by the size of these, printed with quality standards typical of an original artwork. We are talking about the feat (and extravagance) of the Taschen publishing house which in 1999 broke all records imaginable with the publication of this legendary photographic retrospective by Helmut Newton in 464 pages in 50 x 70 cm format, with a lectern included, designed by Philippe Starck himself, something that is perfectly understandable, not only because of the size of the book in question, but also because of the 35 kilos of weight of each copy. All this for the modest price, according to the web review of the same publisher, of 17,500 euros, earning it by its own merits to be considered as the most expensive book published in the 20th century.

The bad news is that, if you have too much money and you want to expand your home furniture with such an investment, Taschen has been hanging the sold out sign for this article for years. In fact, the 10,000 copies of Sumo flew in a short time after its first edition. The good news is that, for the rest of you, you now have the low-cost edition on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the original publication, in a less pretentious format (27×38 cm) and at a much more earthly price, 100 euros (even less with some online offers). This re-edition contains the same content published at the time, with its 464 pages, revised and updated by June Newton, Helmut Newton’s wife until his death in 2004, and is complemented by the making of the original Sumo project. In addition, we talk about Taschen Publishing, synonymous of exquisiteness and maximum quality in all its editorial projects, whether they are at normal size or at a stretcher table.

For those who do not know the work of Helmut Newton (which is enough for you), we talk about one of the totems of 20th century photography and any future time by extension. His influence on fashion and portrait photography is indisputable, but without a doubt it is his photographs of the female nude that marked a before and after in this genre, combining glamour, eroticism and beauty, and a certain dose of voyeurism, sometimes within the limits of the sexual stereotype of women, something that perhaps prevents more than one from understanding and contextualizing in these times his contribution to the world of photography if he does not do so with an open mind and knowing well all the work of this photographer. Surely Newton would come out on top today with that famous phrase of his: “Look, I’m not an intellectual, I just take pictures.

And if Sumo is not enough for you, here is a bonus to track complete his retrospective in your shelf (if you can) with his snapshots shot in Polaroid system.

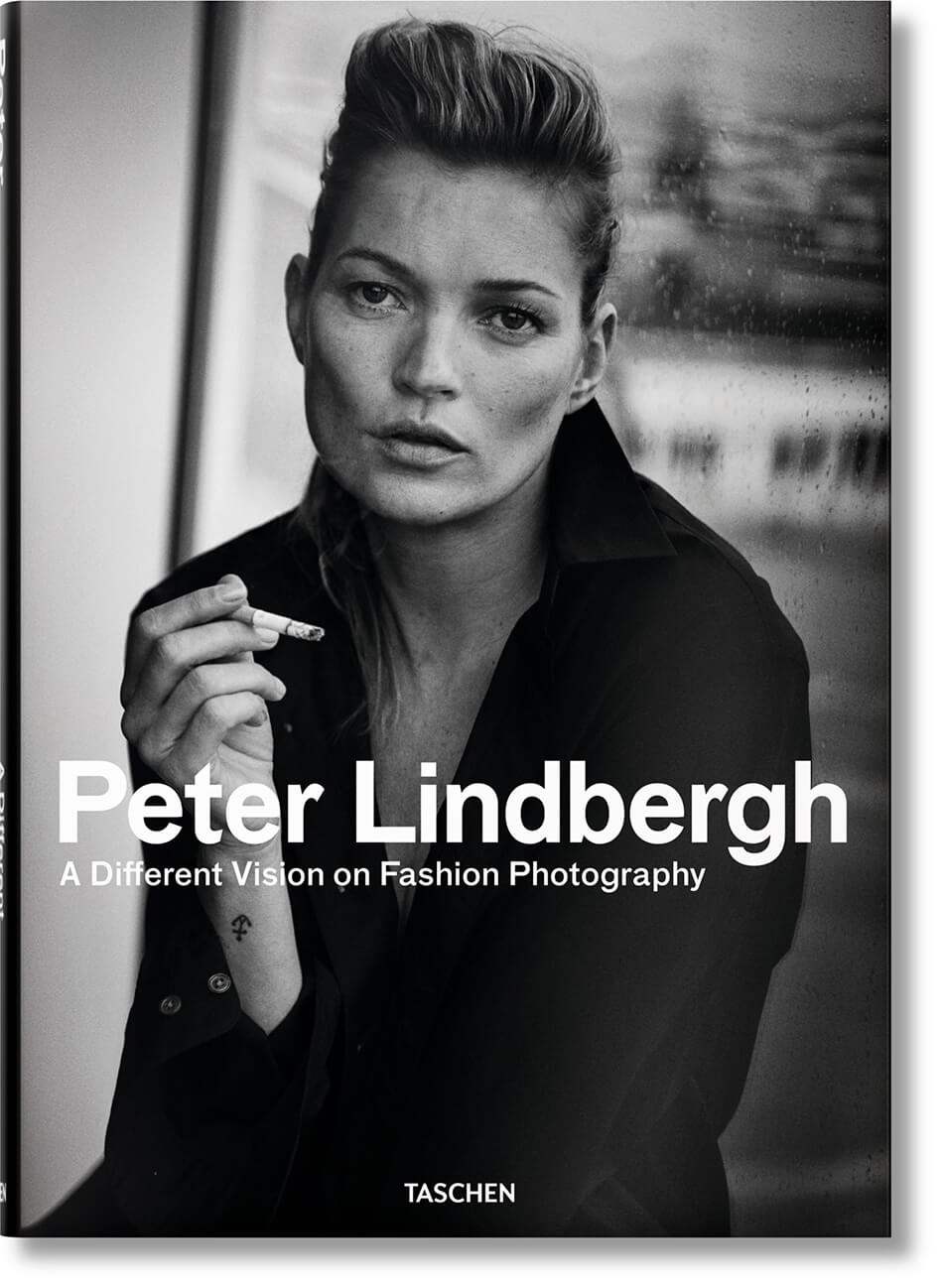

A Different Vision On Fashion Photography by Peter Lindbergh

Continuing with the same editorial, we go to another essential one that also revolutionized the codes of fashion photography and is considered the architect of the phenomenon of supermodels in the early 90s. I’m talking about the recently deceased Peter Lindbergh and the almost 500 pages of A Different Vision On Fashion Photography, again with the indisputable quality and exquisite taste that characterize Taschen’s publications.

Peter Lindbergh started photography late, in his thirties, and in his early years as a photographer for Stern magazine he even coincided with Helmut Newton. But it was in Paris where he acquired worldwide recognition, standing out for his particular conception of fashion photography, almost always in black and white and in some aesthetic codes typical of the documentary, far from any style of that time (early 80s). His visual language, full of naturalness and intimate style, captivated the most prestigious fashion brands, making Lindbergh one of the most sought-after photographers, despite the fact that in his images fashion always turned out to be a pretext and rarely the focus of attention.

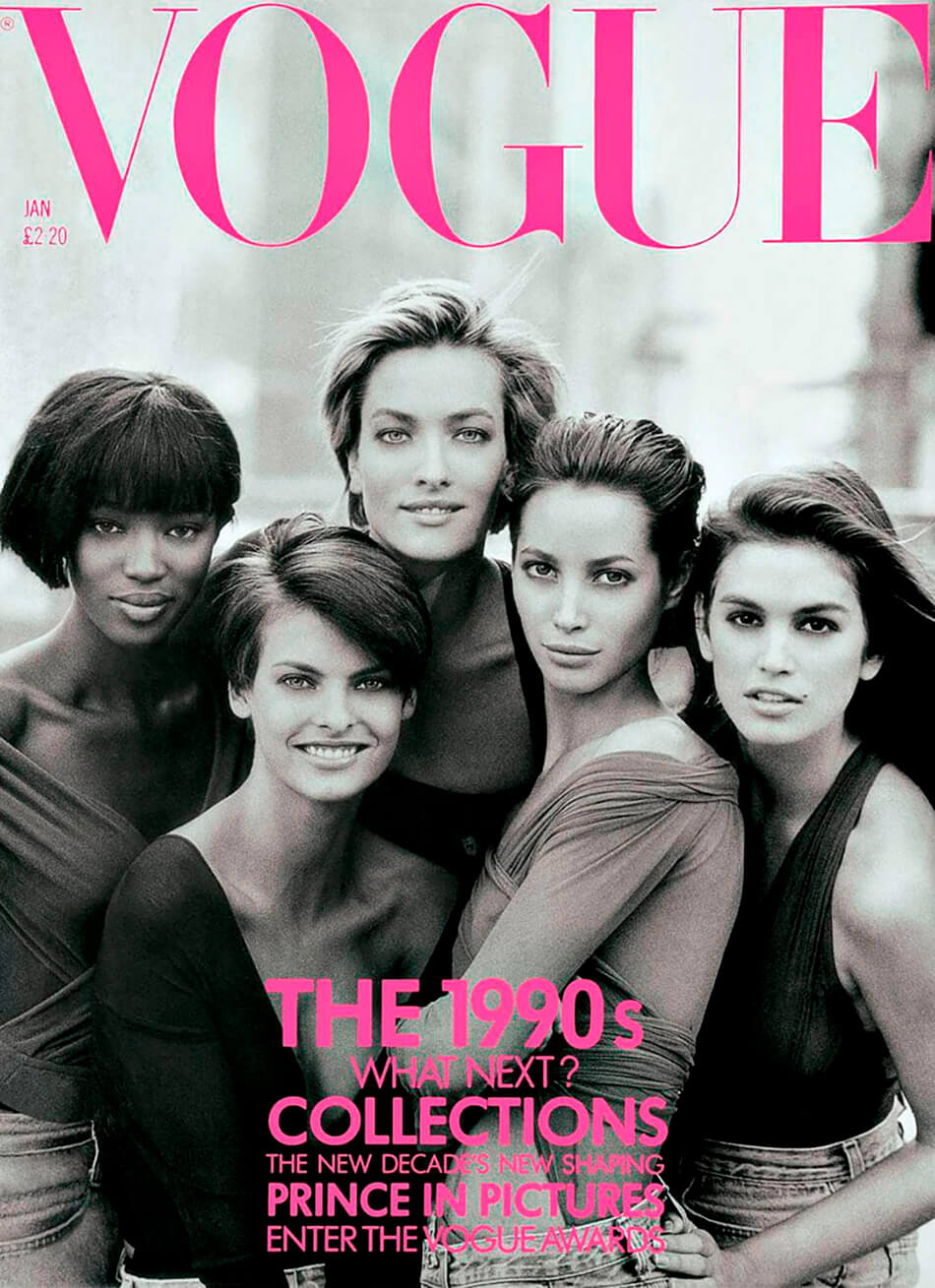

Lindbergh took the cover photo for the January 1990 issue of British Vogue, for which he chose five emerging models, almost unknown at the time, and photographed them in the middle of a New York street, practically without makeup and looking at the camera in a simple way as any group of young people could pose at a meeting of friends. Their names: Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Tatjana Patitz, Christy Turlington and Cindy Crawford. That photograph became a true icon that revolutionized the concept of beauty in the world of fashion and gave rise to the controversial phenomenon of supermodels in the 1990s, ceasing to be considered as simple “mannequins” and taking on the role of a rock star, which even eclipsed the very brands for which they posed or paraded.

A Different Vision On Fashion Photography is an extensive and complete journey through the work of one of the great references of modern photography, who died unexpectedly in September last year, at the age of 74, practically with his camera in hand and in full activity, while preparing his first self-commissioned photographic exhibition in the Museum of Kunstpalast Düsseldorf, in his native Germany. It was precisely from this exhibition that the posthumous publication of another fantastic and recommendable catalogue from the Taschen publishing house was born: Untold Stories.

Taschen is currently preparing a new edition of A Different Vision On Fashion Photography under the new title Peter Lindbergh. On Fashion Photography.

Beneath The Roses by Gregory Crewdson

I discovered Gregory Crewdson’s work in the fantastic exhibition dedicated to urban life, Lost in the City, held by the IVAM in Valencia in the summer of 2016. The first thing that caught my attention in his photographs was to recognize in them some well-known actors such as Julianne Moore, William H. Macy or Tilda Swinton in images that looked like individual frames taken from any American film. Those images belonged to the Dream House collection which has been published in book format and also in individual prints, in limited editions difficult to find at this time and if so, always by export from the U.S. and at a cost, both product and shipping, quite high.

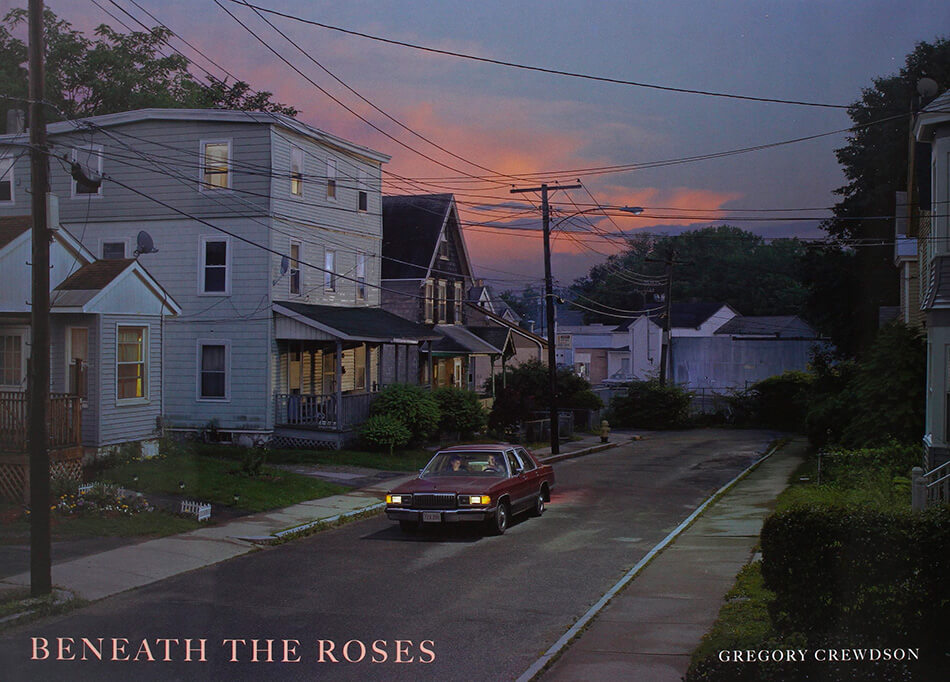

Luckily, this is not the case with Beneath The Roses, published by the American publisher Abrams Books in 2008 and also with an excellent quality of printing and photographic reproduction. This catalogue is currently available for around 60 euros through online sales and although it is not as extensive as the Taschen catalogue mentioned above, its images can be enjoyed in an appreciable 41 x 30 cm format.

The production of each photograph by Crewdson is typical of a film shoot, using practically the same lighting processes and resources used in the cinema, both in reduced spaces and in real open settings, for which it always has a large human and technical team, turning entire streets into authentic film sets.

However, Gregory Crewdson’s final photographs, despite the spectacular nature of their gestation, show his protagonists immersed in a disturbing solitude and confusion, lost in the midst of desolate urban landscapes, empty and dark streets, or everyday interior rooms that still further accentuate the human fragility of those who inhabit them.

In Beneath The Roses, each photograph is meticulously choreographed. In it we find vast urban landscapes in which we can discover the apparently normal lives of the different inhabitants who populate them. There are windows in the foreground or in the distance of the scene that invite us to imagine the history of the people who are seen through them. There are cars standing in the middle of a lonely road, or in front of an empty supermarket where we discover their occupants in ambiguous situations that provoke a disturbing need to know what is happening in those spaces. It is as if, on seeing each image in the catalogue, we become voyeurs behind our own window or in the undergrowth of an abandoned lot, witnessing an external reality that is tremendously unsettling and at the same time captivating. But the climax of the work occurs in the scenes in which the author allows us to literally enter that human microcosm of which we only saw a part from the outside, because the interior is even more overwhelming, and the everyday becomes a hieroglyph that we must resolve, giving detail to each reflection in the mirror, to each half-opened door, to each dimly lit room, because each part of the image is essential to understand or imagine the whole.

The Americans by Robert Frank

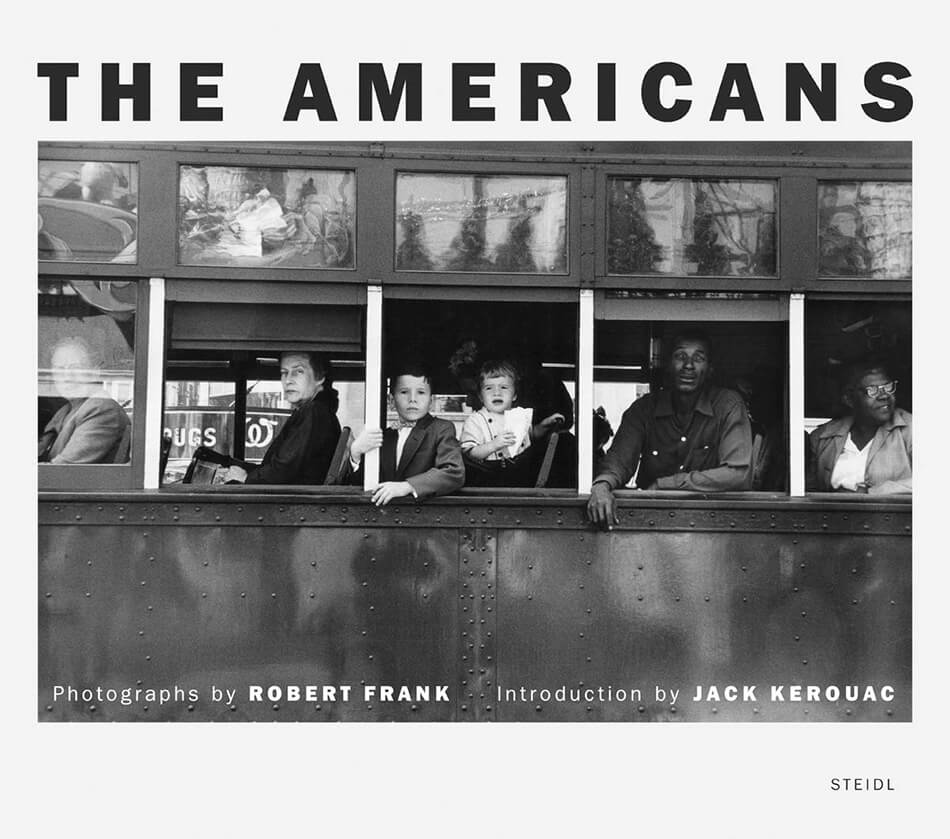

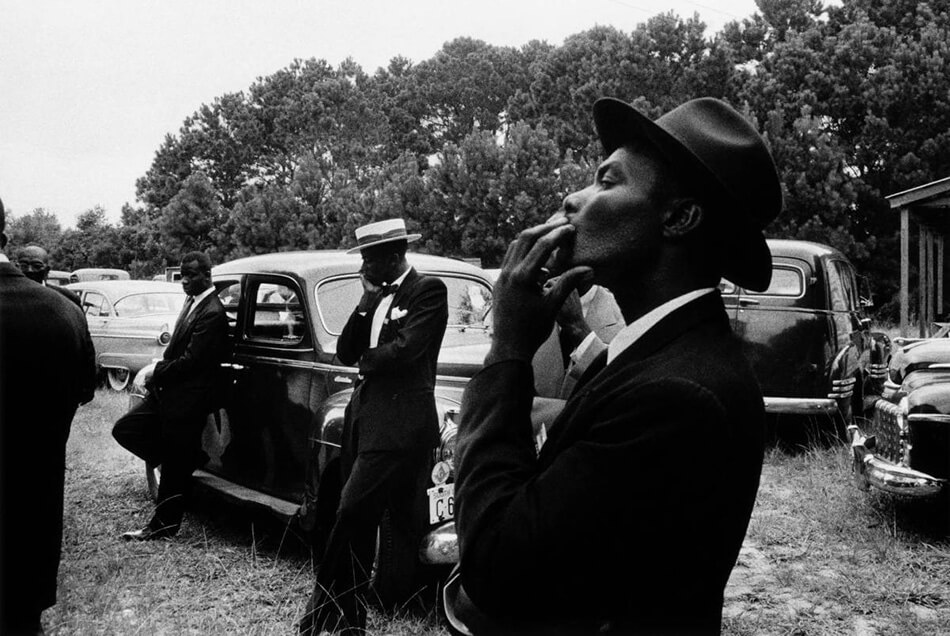

Without a doubt, September 2019 was a black month for the world of photography. On September 3, Peter Lindbergh died unexpectedly, and six days later, at the age of 94, one of the living legends of photography until then, Robert Frank, a key figure in 20th century graphic journalism and author of one of the fundamental photographic books on the shelf of any photography lover: The Americans.

In 1955, Robert Frank already had some recognition as a photographer, having emigrated from Switzerland to the USA in 1947. At first, Frank felt a real fascination for the country that had taken him in and this led him, under the patronage of one of his great influences, the photographer Walker Evans, to apply for a scholarship to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. The proposal of his application is to travel all over the United States, camera in hand, and make a kind of visual report of American society and its customs, seen from the perspective of an immigrant who is practically unaware of the complex idiosyncrasies of his new and enormous country, which frees him from any prejudice when it comes to capturing the reality (or realities) of what he encounters along the way.

Once the scholarship is granted, Frank gets an old Ford Business Coupe, a few cameras and a lot of film, and starts his own road movie that takes him through more than 40 states over the course of a year and a half. But what he finally captures with his cameras has little to do with the American dream. What he finds is a country of significant contrasts, with shocking class differences between rich and poor, almost third world, America, and with the long shadow of racism present at all times. “A sad poem of America captured in photographs” in the words of writer Jack Kerouac.

The final result was more than 28,000 snapshots that led Robert Frank to spend almost two years of his life selecting the little more than 80 photographs that were finally published. But the America portrayed by Frank was so raw and sad that few American publishers were willing to publish that project at that time and, finally, the first edition of The Americans was made in France under the title Les Américains, including texts by illustrious intellectuals of the time such as Henry Miller, Simone de Beavoir, John Steinbeck and William Faulkner.

It was not until 1959 that the book as we know it today was published. It was Grove Press that was in charge of the first edition of The Americans in the United States, in which the original texts of the French edition were eliminated, due to their “un-American” tone, being replaced by an introduction by Jack Kerouac, which helped to boost the sale of a catalogue that at first received a lukewarm reception among the public and harvested more than one fierce attack from the American specialized press. All of this caused Robert Frank to distance himself from that first fascination with his adopted America, being very critical from then on of a society obsessed with a “dream” that in reality turned out to be a veil for not being aware of its loneliness, its fear and its confusion.

The Americans is now available for sale online, in a Steidl edition, in 21 x 18 cm format and for about 35 euros, a more than reasonable price for one of the mythical publications in the history of photography.

Vivian Maier

Vivian Maier‘s story is, without a doubt, one of the most surprising photographic events of this century. The posthumous discovery of an unknown artist who practically concealed her vocation as a photographer and a talent to which she possibly never gave any importance, and which was discovered and raised after her death by simple life’s coincidences.

In 2007, a young historian named John Maloof was conducting research based in Chicago’s Portage Park neighborhood with the idea of publishing a picture book, when he located several belongings that had been abandoned in a storage room of a furniture warehouse in an auction house. Among all that material, a series of rolls of undeveloped film appear that he acquired for less than $400. Maloof, after developing some of the reels and reviewing their contents, decided to discard them from his research project and made some of those images available to collectors through the Internet. It was then that the American critic and historian Allan Sekula discovered those images and contacted Maloof, surprised by their talent and historical value, giving rise to one of the most resounding photographic findings of recent years.

Maloof, already aware of the value of that material, decided to undertake a detailed research process to locate the authors of those photographs shot between the 1950s and 1990s between Chicago and New York. By the time he discovered that behind that amazing graphic material was a simple nanny named Vivian Maier, who was fond of photography, it was too late. Mayer had already died in April 2009 in an old people’s home, at the age of 83, alone in total anonymity.

Maloof’s research led him to the Gensburg family, for whom Vivian had worked for almost 20 years as a nanny, and thanks to this she was able to retrieve Maier’s correspondence, newspaper clippings and various photo films. She also located the shop where Maier used to have his photos developed when he could afford it, which was not often the case. In total, she collected more than 100,000 negatives during the course of her research, many of which had not yet been developed. She was able to locate them chronologically because the negatives developed by Vivian Maier herself had the location and the date they were taken indicated.

Vivian Dorothy Maier was born in New York in 1926 to an immigrant family (French mother, Austrian father). As a child, she returned to France with her mother, where she lived until, at the age of 25, she decided to return to New York, where she began to alternate various jobs as a nanny, which enabled her to acquire a Rolleiflex medium-square format camera with which she would take almost all of her black-and-white photographs over the course of 40 years.

No one knows how Maier acquired his knowledge of photography, although prior to his second stay in the United States he is credited with some images taken in France with a Kodak Brownie. It is known that in some of the houses he worked for he was able to have a bathroom next to his room where he could set up a darkroom and develop some of his photographs. But the truth is that most of the images she took were not developed because she usually did not have enough money to afford it, and most of the rolls ended up piled up, and even abandoned, as Maier changed families due to her job as a nanny.

Maier seemed to enjoy the photographic process more than the expectations of the result and was probably never aware of its potential.

Vivian Maier’s rescued photographic work has nothing to envy to that of the great photographic chroniclers of 20th century North America, even though she herself did not take the result of her love of photography seriously during her lifetime. Maier seemed to enjoy the photographic process more than the expectations of the result and was probably never aware of its potential. But the fact is that Maier’s photographs are of unquestionable quality, not only when it comes to choosing the frames in a format, the square, whose process with a Rolleiflex is not exactly the most suitable for practising Street Photography, but also that her images are resolved with a proximity and clarity when it comes to showing the photographed subjects, which seems more appropriate for a meticulous photographic studio work than a documentary one. In Maier’s images there are no blurs, no shaky pictures, no excessive grain. Everything is perfectly frozen, with all its details 100% appreciable. A real feat for someone who possibly didn’t even stop to think about the transcendence of what he was doing… He was simply taking pictures….

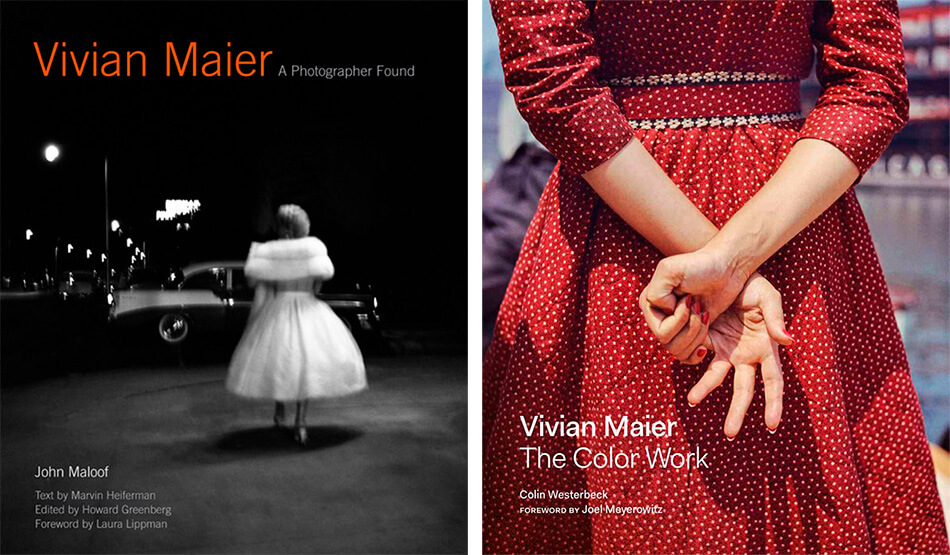

There are currently two very interesting books that can be purchased online, Vivian Maier. A Photographer Found, edited by John Maloof himself, which brings together some 250 images, many of them previously unpublished, and Vivian Maier. The Color Work which focuses on the possibly least known stage of the photographer, that of her color photos captured with the same Rolleiflex but also with other 35mm cameras that she used to load with Kodak film. Both have been published by Harper Collins Publishers Publishing.

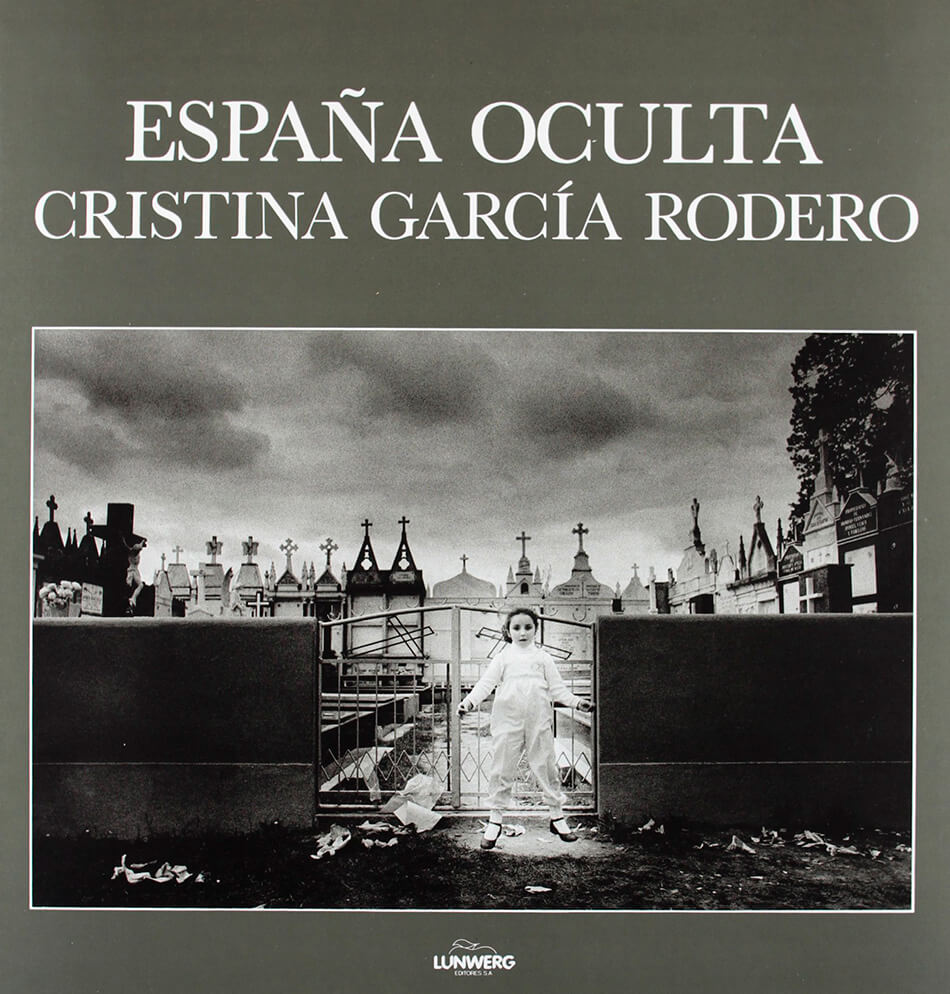

Hidden Spain by Cristina García Rodero

And now we come to a book that unfortunately is already out of print and can only be found on the second-hand market for collectors, at unaffordable prices, but due to the relevance it had at the time of its publication and the category of its author it is considered one of the best graphic catalogues published in Spain.

To talk about Cristina García Rodero is to talk about a reference in documentary photography, a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando and the first Spanish photographer to be part of the prestigious Magnum Agency.

In 1989, the Lunwerg publishing house published España Oculta, a book with 126 photographs taken by a Spanish photographer practically unknown at the time, Cristina García Rodero, who had received a grant from the Juan March Foundation in 1973 to carry out a photographic project. Her initial idea was to travel around Spain with her camera taking photos in general, but after witnessing some of its most peculiar customs, she decided to focus her work on popular festivals and traditions, some of which were already disappearing in favour of modern times that were approaching in the changing Spain of the end of the 20th century.

I remember when I bought this book, back in 1993, that the feeling I had as I turned its pages was that of seeing in pictures a very old-fashioned Spain, as if those photographs were from very distant times. I did not know then the period in which these had been taken until when I checked the dates of each snapshot, already in the final pages, I found myself with the surprise that some of them were not more than 4 or 5 years old, and in general they had been taken in an interval of between 10 and 15 years. In spite of having been born and lived in a rural zone in which it was not very difficult to find some similar picture in its traditional celebrations, the impact that produced me the images of García Rodero, being still very young, is something that has lasted in my memory throughout the years.

Without a doubt, Hidden Spain is one of the most stark and poignant photographic reports on our country ever made. A reality that shakes, that even comes to seem dystopian, simply captured from the traditional festivals and Spanish folklore of the end of the century and that is difficult to recognize and even accept, despite the fact that some of these customs are still in force today and not only in the most remote villages of our country.

Essential.

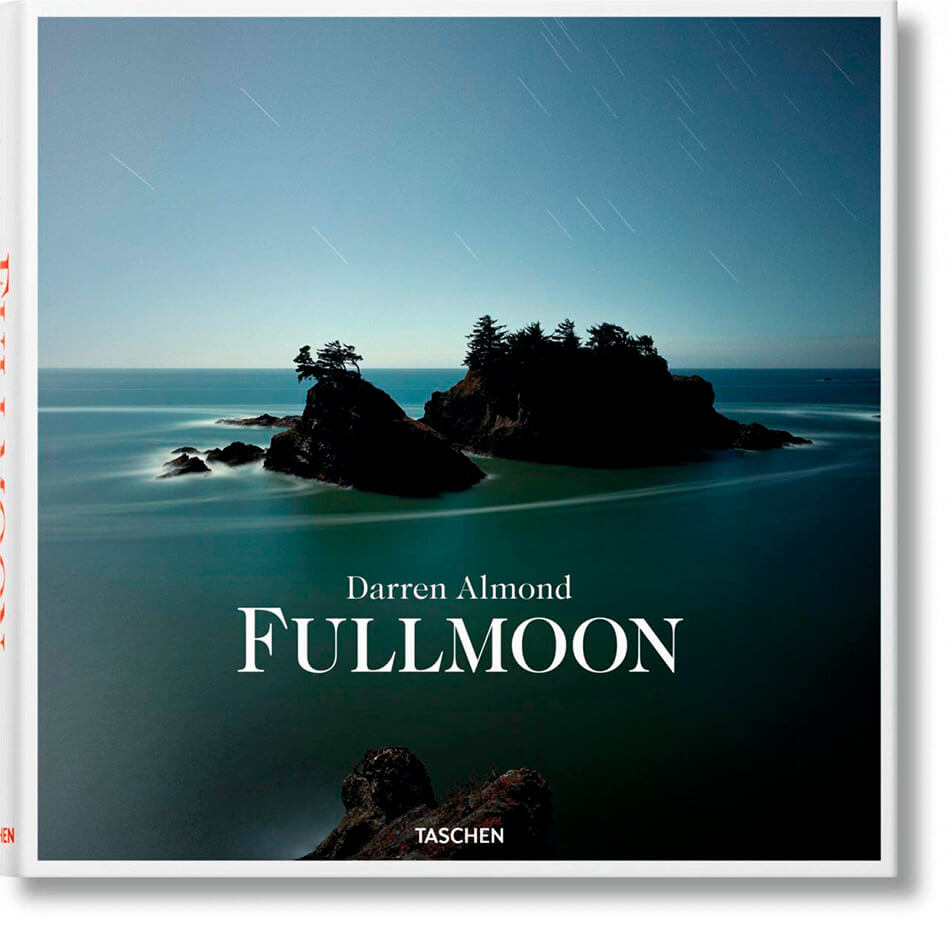

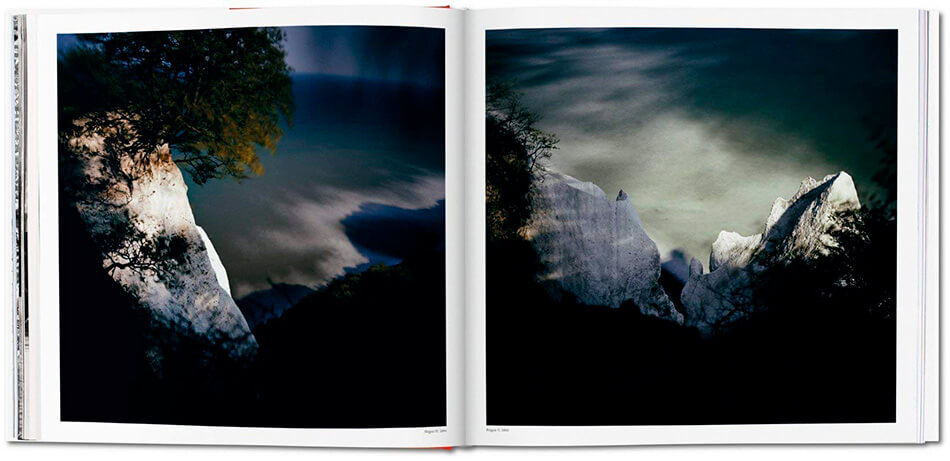

Fullmoon by Darren Almond

One of my recent acquisitions has been the book Fullmoon, also published by Taschen Publishers and the work of British multidisciplinary artist Darren Almond, who was totally unknown to me until I discovered his work on the Internet a little less than 3 years ago. At that time I was dislodging the margarita with respect to the printed publication of my own photographic project, Quadratures, Mínimes and found in Almond’s images a clear connection with my conception of space and landscape applied to those photographs that I had been shooting over the years, outside of my professional work.

Fullmoon is a fascinating collection of photographs taken with the full moon as the only source of light. The result, halfway between dreaminess and abstraction, turns the photographed landscape into something typical of a world different from ours, unreal and inhospitable, the result of the technique of photographing in long exposure times (15 minutes or more) that allows us to discover what the human eye cannot see with the naked eye in such extreme light conditions.

Without a doubt, Fullmoon is an interesting experiment that gives us a particular vision of landscape photography, far from the canons of a postcard image. That landscape, in the hands of Darren Almond, is nothing more than the means to capture in his images atmospheres and environments that, despite being captured in real natural spaces, transcend that reality and are shown as if they had been extracted from a world parallel to ours… Similar, but not the same.

This 400-page catalogue, magnificently laid out and printed, is now available for around 50 euros for sale online, in 30 x 30 cm format.

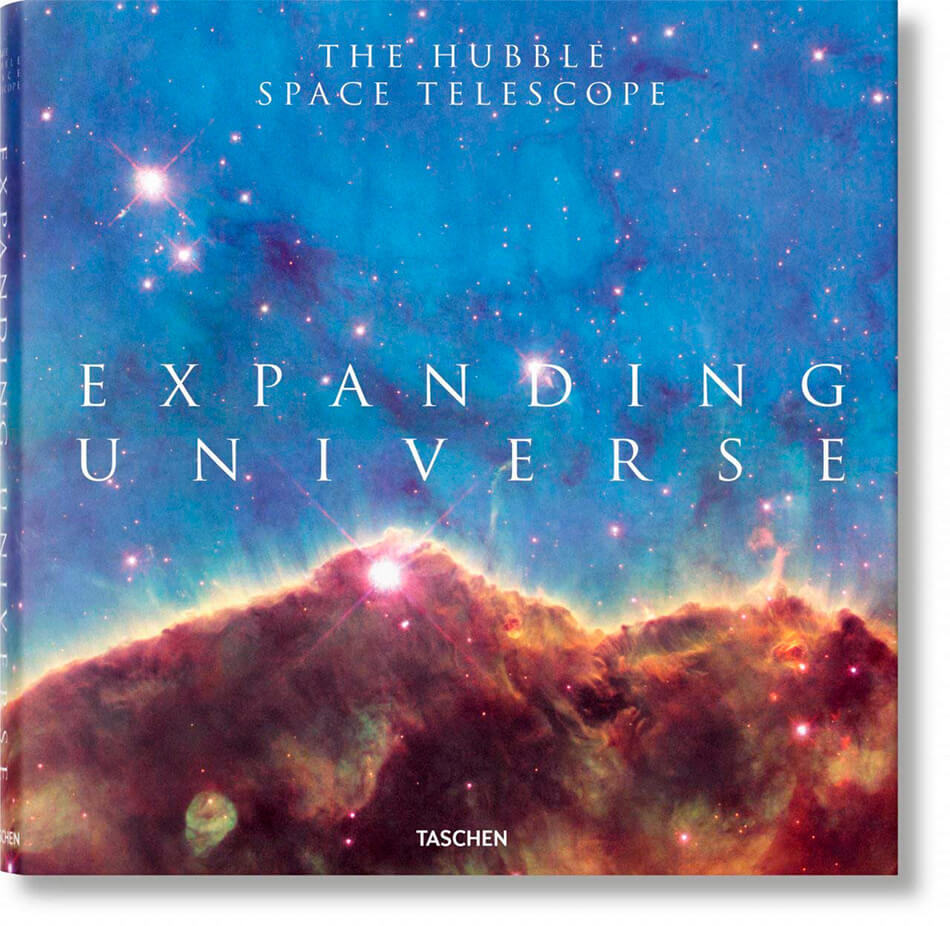

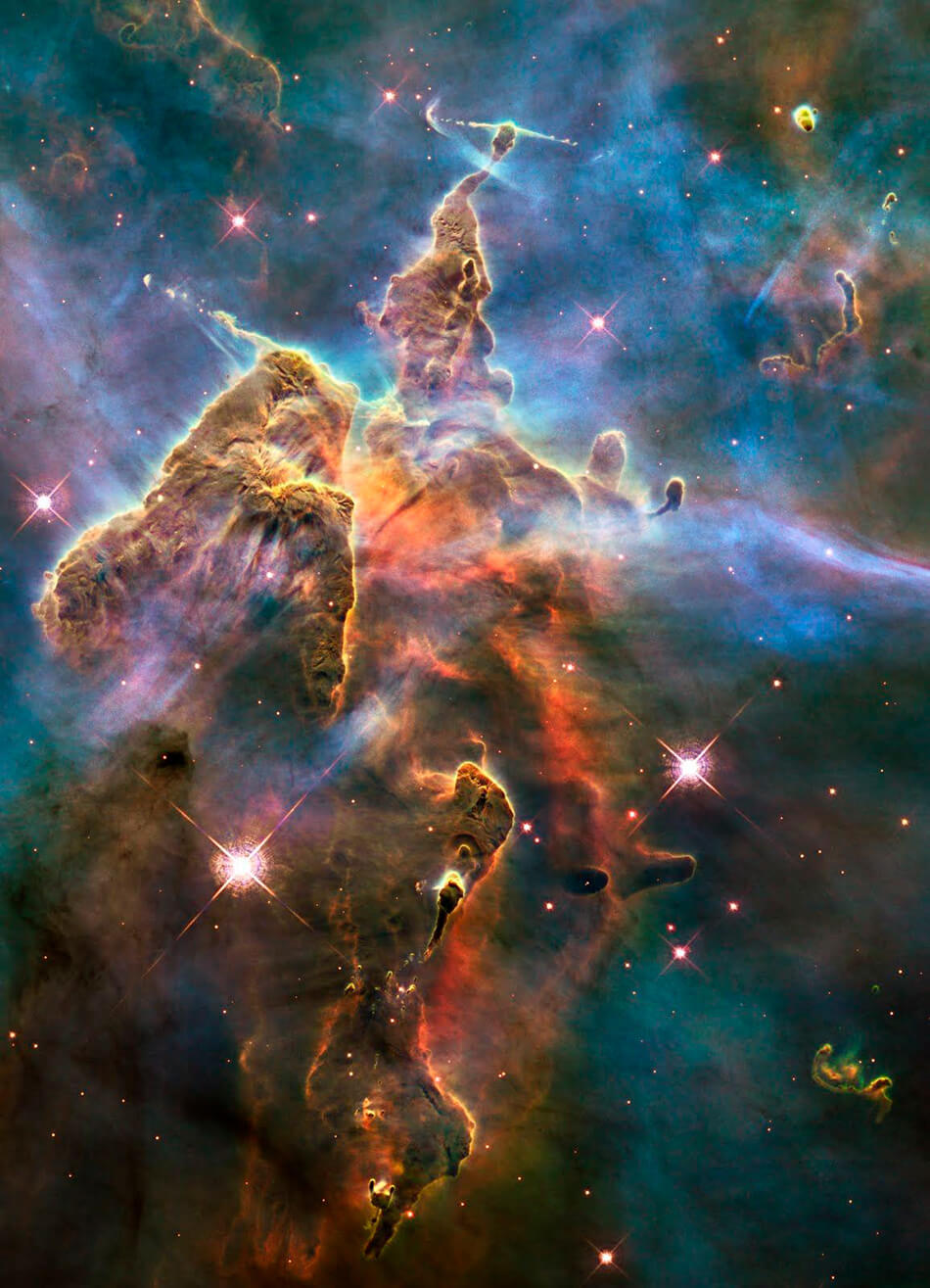

Expanding Universe. The Hubble Space Telescope

And finally, we jumped from the earthly to beyond the confines of the universe, because we cannot ignore a field of photography that has been gaining followers in recent years, thanks to the technological advances of digital cameras and that, without a doubt, has provided us with some of the most spectacular and beautiful images of the Milky Way captured from Earth. I’m talking about astrophotography.

But we cannot talk about astrophotography without giving Caesar what is Caesar’s, because it would be impossible to understand the magnitude and relevance of what this photographic field represents without going through the historical and scientific milestone that was the placing in orbit of the Hubble space telescope, the “star king” of modern astrophotography.

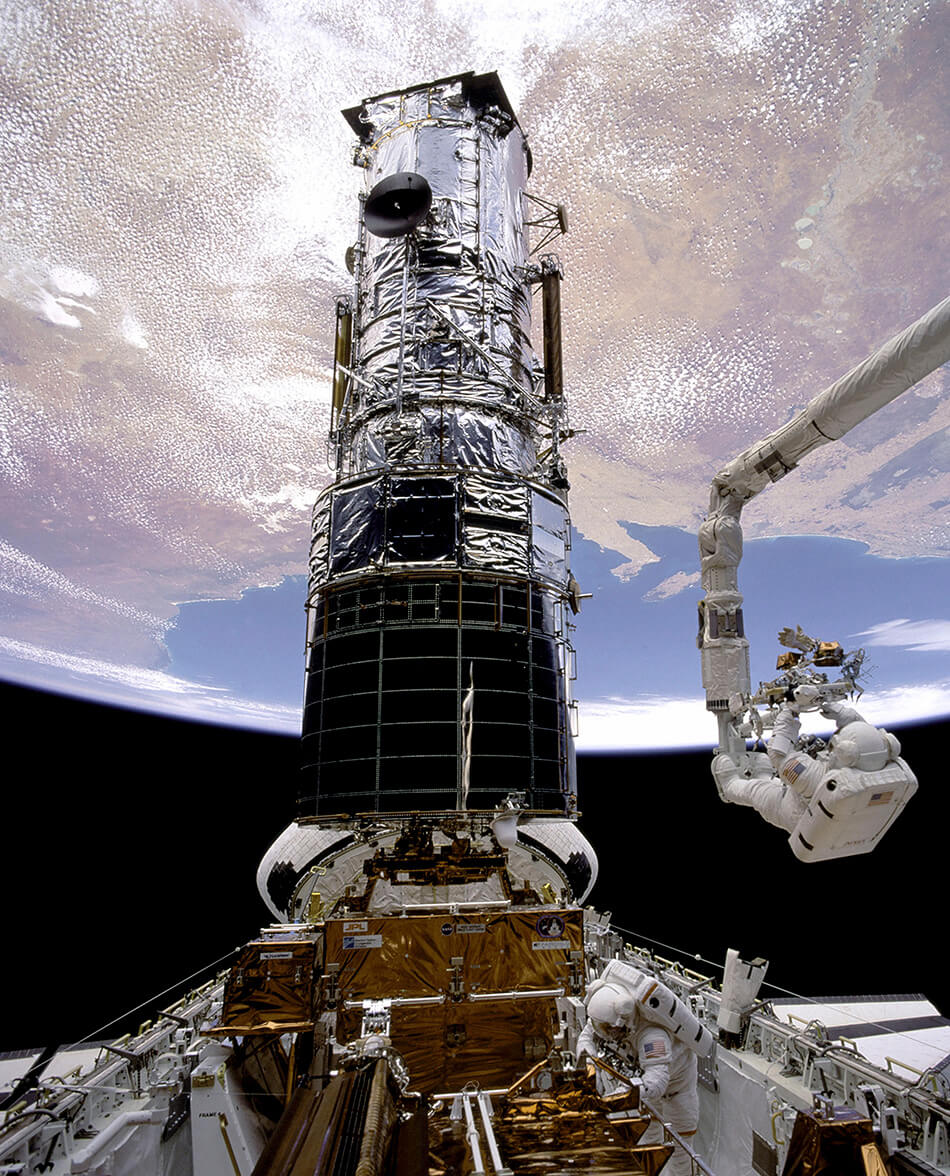

Before Hubble, the only way to capture images of the universe was through ground-based telescopes, which are often affected by the weather and even light pollution. In addition, our atmosphere absorbs electromagnetic radiation at the infrared wavelength, considerably affecting the quality of the images and making the capture of some spectra impossible. To have a telescope in orbit, which would not be affected by the distortions of light coming from space, typical of the Earth’s atmosphere, was something that the German rocket expert Hermann Oberth had in mind as early as the 1920s. Of course, it took many years for technology to make the construction of such a device possible, and it was in 1977 that the American Congress approved the project, thanks to the impetus given to it by the American physicist Lyman Spitzer.

Originally scheduled for launch in 1983, Hubble had to wait a few more years due to various delays and especially the consequences of the accident of the space shuttle Challenger that in 1986 disintegrated in the air shortly after take-off, ending the lives of its seven crew members. It is finally in 1990 when the large space telescope is put into orbit after having tripled the initial budget of the project.

But it still had to pass the acid test, which was to know its true capacity to fulfill the purpose for which it had been built: to see the universe from a perspective never before seen. And it is with the reception of the first images that astronomers come face to face with the harsh reality. The images captured by Hubble were not sharp as they showed an unexpected blurring due to a defect in the polishing of the main mirror. But NASA scientists didn’t give up and taking advantage of the fact that Hubble had been prepared to be manipulated in space by a space shuttle, they worked for two years to solve the problem and finally, in 1993, the first of five manned missions that have been necessary during the 30 years of life of one of the most impressive photographic mechanisms ever built by human beings took place. That 1993 mission to repair Hubble’s main mirror gave us one of the most iconic postcards of the space adventure, that of the astronauts of the shuttle Endeavor floating through space while repairing the telescope.

And it is from that moment on, with Hubble already wearing its particular “glasses” to correct our sight, that the most recondite universe begins to be discovered in all its colossal splendour, with a clarity and proximity that is shocking, completely changing the meaning of our existence and our condition (minuscule) as human beings in the face of that infinite immensity.

But the Hubble photographic milestone goes much further and is even more disturbing if we stop to think about how light wavelengths work. The human eye captures a portion of the spectrum of light, which we call the visible spectrum, which travels through space at a speed of 300,000 kilometres per second. That means that if the sun is 150 million kilometres from the Earth, the light from the star that reaches us is the one that has been produced 8 minutes and 20 seconds before we see it, which is how long it takes light to travel the distance that separates us from it. Well, if we transfer this to the firmament when we contemplate the stars at night, we find the paradox that the light that reaches us from the stars is not the light of today, but that we see the light emitted in the state in which those stars were years ago. For example, the nearest star to our solar system is Proxima Centauri and it is at a distance of 4.22 light years. What does this mean? Well, that the light we see from Proxima Centauri Earth is the light that has been produced 4.22 years ago and not the one that is being emitted at this moment.

Let’s transfer this to the operation of Hubble, which not only works in our visible spectrum, but can also capture light outside of it, especially infrared light that allows it to capture objects in the universe in, so to speak, “dark” zones. As Hubble’s vision moves into the far reaches of space, it is not only discovering us as we are, but also calculating how old this one really is, since the farther away the object it manages to capture, the closer it is to the light from the beginning of the universe.

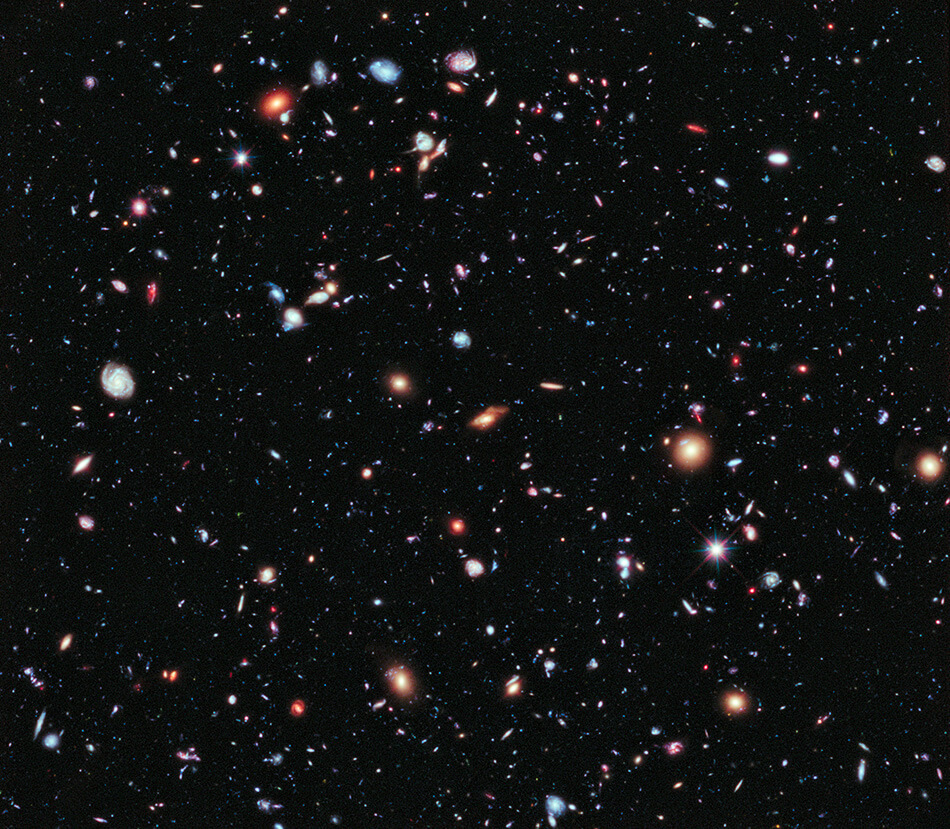

The event that completely changed our existence occurred between September 3, 2003 and January 16, 2004, when Hubble pointed to a small area of space and captured the deepest image ever taken of the universe in the spectrum of visible light. This is what was called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field.

The event that completely changed our existence occurred between September 3, 2003 and January 16, 2004, when Hubble pointed to a small area of space and captured the deepest image ever taken of the universe in the spectrum of visible light. This is what was called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. The result is an image from a very small portion of the universe in which you can see various galaxies in different sizes, shapes and colors. It is estimated that the light from these captured by the Hubble was emitted more than 13,000 million years ago, only 800 million years away from the calculation of the birth of the universe, which we know as the Big Bang.

From a photographic point of view, don’t tell me that all this isn’t overwhelming. Well, this very month, once again by Taschen’s grace, the book Expanding Universe. The Hubble Space Telescope will be released on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the putting into orbit of the Hubble space telescope, and also at a very interesting price (30 euros) taking into account the quality of this publishing house and that we are talking about a catalogue of almost 300 pages with internal fold-outs and in a closed format of 30×30 cm. A fantastic opportunity to see in print what are undoubtedly the most important photographs in the history of mankind, not only because of the technological expertise that has made them possible, but above all, because it is the most enlightening visual document of our true human condition… We are simply stardust…