Photography as seen through the eyes of cinema

Contenido

Parallel paths in photography as seen by the cinema

When talking about photography as seen by cinema, the first thing that should be said is that cinema exists because photography existed before it, that is an indisputable fact. That both cinema and photography have followed independent, but always parallel, paths is also a proven fact. Cinema would not be understood without the role that photography plays in the entire filmmaking process. In fact, practically all of the visual impact that its images produce depend on the work of one of the most important technicians in any film: the director of photography.

He is in charge of reproducing the way each scene is shown, with its framing, lighting and atmosphere. And the technical process behind the visual aspect of each film frame is not very different from that of any photographic shot, be it with ambient light, artificial light, or a combination of both.

Not even the post-production of the image in each field is different. In the past, the processes were chemical, whether for colour negative, black and white or slides in the case of photography, as they were for celluloid, the positive of a cinema film. Now, almost the entire development and post-production process, both in film and photography, is done by digital techniques which, if not sisters, are at least cousins.

That cinema exists because photography existed before it is indisputable. That both cinema and photography have followed independent, but always parallel, paths is also a proven fact. Cinema would not be understood without the role that photography plays in the whole process of making it.

The language of film

On the other hand, photography has also been nourished, and continues to be nourished today, by the language of film. Not only when composing its own scenographies, but also when contextualising its own visual narrative. An example of this are the famous storytellers by Duane Michals. Small stories, in many cases with the depth and complexity of a film story, told from a sequence made up of several photographic shots.

A much more obvious example is the case of photographer Gregory Crewdson, whose elaborate images require the technical and human equipment of a large film set.

However, it is not easy to find films in which, beyond the resource or the anecdote, photography is openly talked about or transcends in a clear and forceful way into the film’s plot. Of course, I am talking about photography as seen by the cinema within fiction, because in the documentary field we can find interesting works such as: The Mexican Suitcase (Trisha Ziff, 2011) or The Salt of the Earth (Wim Wenders, 2014).

Models

There are even some curiosities that straddle the line between documentary and advertising, such as Models (1991), that particular ode to the world of supermodels in the 90s by photographer Peter Lindbergh and which, seen now almost 30 years later, seems overwhelmingly banal if it were not for the exquisite black and white of its moving images, closer to Lindbergh’s own photographic style than to the codes of a documentary.

The iconography of photography as seen through the eyes of cinema

Nor will I ignore the fact that the iconography of photography has been present in countless scenes in cinema throughout its existence. Iconic is the image of James Stewart with a camera and a huge telephoto lens spying on his neighbours in Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock 1954). Just as iconic is the dance between Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn, bathed in the red light of an “old-fashioned” photographic laboratory in Funny Face (Stanley Donen 1957).

And of course, within photography as seen by cinema, there are also characters based on photographers, such as the one played by Julia Roberts in Closer (Mike Nichols 2004), or Buscapé, the boy who becomes a photojournalist observing the harsh reality of the favela in which he lives in Rio de Janeiro in the surprising and adrenalin-pumping City of God (Fernando Meirelles, 2002).

And without a doubt, one of my favourites, the photographer who captures in images the covered bridges of Iowa (USA) for National Geographic, played by Clint Eastwood in that great film that was, and is, The Bridges of Madison (Clint Eastwood, 1995). And we could go on like this for a long time…

Photography as seen through film: a mechanism for remembrance

Cinema has not been exempt from showing photography as an effective mechanism for remembering. It is possibly the most widespread attribution to the act of photographing in domestic use almost from its beginnings, apart from artistic, journalistic or scientific disciplines…

We photograph to remember. Although now, in the digital age of the image, photography has been subjugated to the whims of rapid consumption that lasts as long as an image remains online in a storie or in the feeds of Facebook or Instagram. Until it is buried by everything that comes “in the queue”. And so it is in the case of the photos chosen, because the vast majority do not go beyond the file stored on a smartphone or on the hard drive of a computer.

Nor has cinema been exempt from showing photography as an effective mechanism for remembering. It is possibly the most widespread attribution to the act of photographing in domestic use almost since its beginnings, apart from artistic, journalistic or scientific disciplines… We photograph to remember. Although now, in the digital age of the image, photography has been subjugated to the whims of rapid consumption that lasts as long as an image remains online in stories or in the feeds of Facebook or Instagram, until it is buried by everything that comes “in the queue”.

Photography as seen by cinema in the 2000s

Memento

In the same vein, 2000 saw the release of Memento. A curious narrative experiment with which the British director Christopher Nolan came to the fore before becoming, with the permission of the Canadian Denis Villeneuve, the creator of some of the best blockbusters for restless minds of the 21st century.

Its protagonist, Leonard (Guy Pearce), suffers from a strange pathology known as anterograde amnesia, which prevents him from storing recent memories in his memory, losing them within minutes.

Our protagonist is involved in a personal investigation to discover the perpetrators of his wife’s murder, a trauma that causes his mental state, presented in several narrative and temporal lines as complex to fit together as Leonard’s methodology to put together the pieces of his puzzle by taking advantage of the brief intervals of time to access his memory, before it resets and his memories fade.

Leonard, who is aware of his problem, devises a system for remembering, which consists of taking advantage of these moments of lucidity to take Polaroid photographs of his surroundings and the people he encounters, and then writing down phrases on the back of the photographs to help him remember the reason for taking each snapshot.

His paranoia about remembering reaches such a point that Leonard does not hesitate to tattoo his entire body with many of the phrases he writes down as his investigation progresses, with the intention that these will serve as clues that will lead him to recover each part of the puzzle he is trying to piece together.

Blade Runner

In Blade Runner (Ridley Scott 1982), a fetish film for me, photography has a special reason to be part of the plot. Although, again, it is not the main focus of attention. But without it, and without the captivating way of showing the importance of images for its protagonists, it would not have been possible to explain their motivations in their odyssey to find out if they are really human or mere artificially manufactured products.

In Blade Runner, the replicants, human-like androids created by the Tyrell Corporation, cling to their memories, even if these are no more than the result of implants in their brains, to justify their existence and their right to be accepted as living, fully emotional beings. The photographs they possess, some taken by themselves, but many others manipulated or simply taken from other people’s lives, become irrefutable proof of what they have lived, or believe they have lived.

Once again, photography seen by cinema as a mechanism for accessing memory, memories, the verification of our existence.

In Blade Runner we talk about a suggestive futuristic artifact of photographic analysis that was the Esper machine, which I talked about extensively in a previous article: Photography in times of #fotografi@ (second part).

Photography as seen through the eyes of cinema in a more direct way

Cinema has also approached photography in a more direct and committed way, and it has gone from being a secondary resource to becoming the leitmotiv of the storyline. It is not that films have been made to talk exclusively about photography, but there are examples, some of them extremely interesting, in which photography acquires a determining dimension. Not only in terms of its presence throughout a film’s running time, but above all as a key cog on which the main plot depends, in which aspects intrinsic to the act of photography and its possible consequences, explored from a cultural, social, philosophical, etc., point of view, are questioned and raised.

Unfortunately there are not many, but of these there are some that for me have a special value beyond styles and the quality of the whole. They are the ones that have left their mark on my process to better understand the dimension of photography as an expressive medium and its stimulating capacity to take us beyond what the eye sees.

Before continuing, I must warn you that the following content contains spoilers, if you haven’t seen the films, but it is impossible to avoid spoilers when you are trying to do an analysis for which certain key scenes have to be disembowelled. So, from here on, which way you go is up to you.

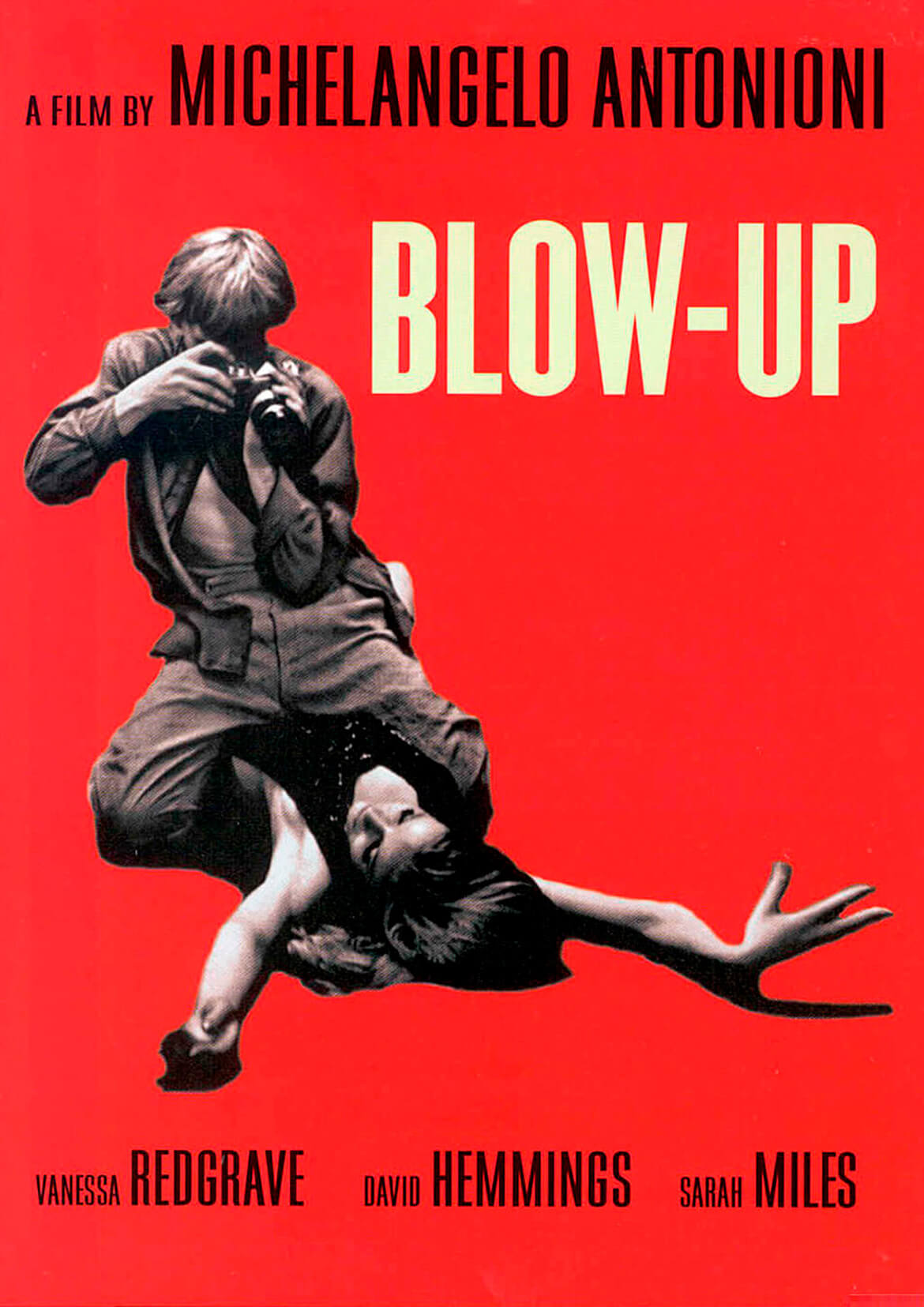

Blow-Up. Discovering what the eye does not see

A good handful of years ago, when I was just a young first-time photographer and my attitude to anything to do with photography, film, or art in general was that of a sponge soaking up water without ever reaching the limit (luckily, I’m still as thirsty…). I was one of those who went to bed quite late and even enjoyed staying up late while I developed photos, read, or watched some of my favourite programmes on TV, some of which were on or went on into the wee hours of the morning.

It was the mid-90s and my weekday night-time activities included waiting for Metrópolis to be broadcast on La 2, which depending on the previous programming could be at any time after midnight, or watching the film in its entirety and the subsequent discussion of ¡Qué grande es el cine! and then connect with TVE’s Cine Club, whose headliner and preliminary theme tune to the film’s broadcast is now part of the imagination of many of us who were night owls in that pre-internet era, when cultural content on television and radio was relegated to a time when the vast majority of mortals were already pressing their ears to their pillows.

Late-night TV shows

Of all the films I discovered during those late-night television screenings, there are two whose sensations during the viewing remain engraved in my memory. Undoubtedly because, despite being considered classics, there was something enigmatic about them that made them totally different from anything I had seen until then. And which, I suppose because of a predisposition to be interested in strange things, got to me straight to the core.

One of them was The Silence of a Man (1967) by Jean-Pierre Melville, an essential masterpiece of that French noir that revolutionised the codes of a genre so genuinely American from Europe and, above all, Blow-Up (1966). The film by Michelangelo Antonioni that every lover of photography should see a couple of times a year so as not to lose their bearings amidst so much artifice in this digital era that confuses us…

Blow-Up

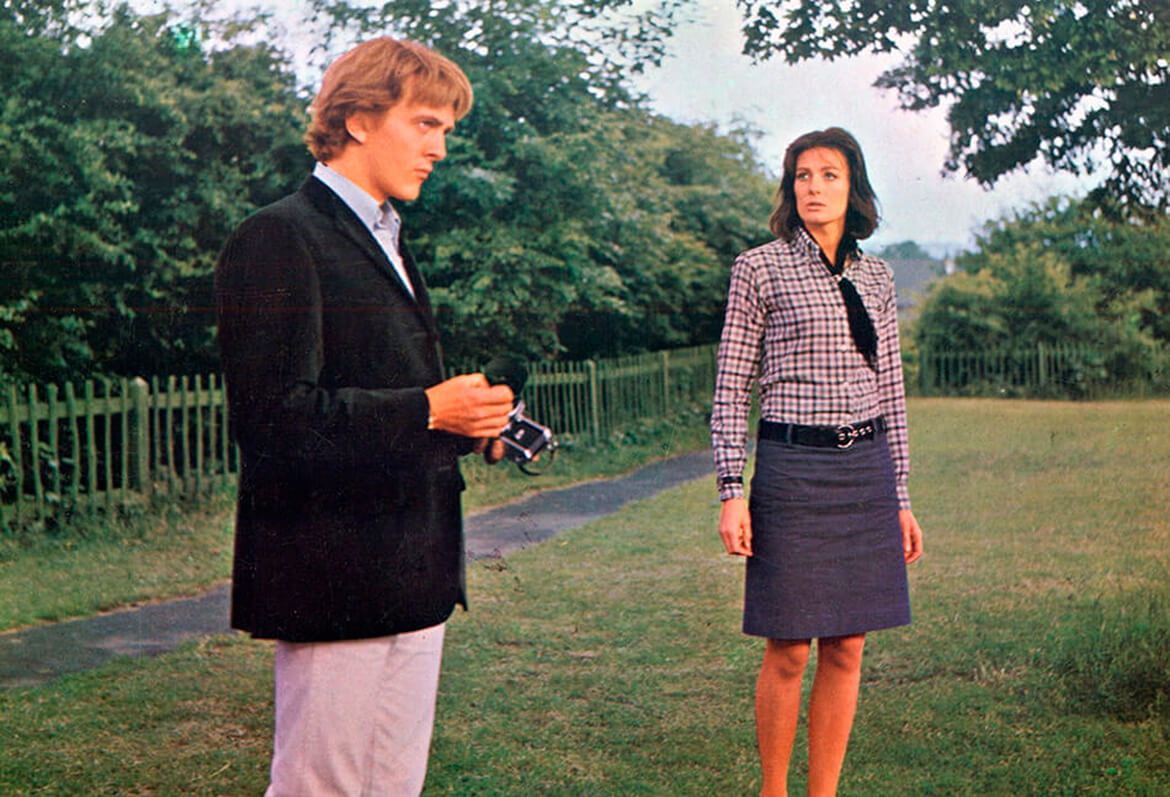

Winner of the Palme d’Or at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival, Blow Up opens in Thomas’s London studio. A famous and coveted fashion photographer, a bit overbearing and overbearing and somewhat misogynistic (it must be said), brilliantly played by a very young David Hemmings, who got the role on the rebound, after Sean Connery himself turned him down for not understanding “not a thing” of what Antonioni intended to tell in the film.

After a visit to an antique shop, Thomas takes his camera and wanders into a leafy park next to it, Maryon Park, on the outskirts of London. For the filming, the paths in the park were painted dark grey and some of the grass areas were pigmented to bring out the green colour.

In the fantastically shot scene, accompanied only by the enigmatic sound of the wind in the trees, Thomas is taking pictures with his Nikon F as he walks through the area until, at one point, he notices the amorous frolicking of a lonely couple and decides to photograph them, taking several shots on the sly.

Suddenly, the girl, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave), notices his presence and accosts him, very upset, demanding that he hand over the photographs immediately. Thomas manages to get away from her, who runs away as he photographs her on the run. But what is his surprise when she, after finding out where he lives, turns up hours later at his studio with the intention of getting the images, even if to do so she has to submit to the photographer’s erotic games and impositions.

An unexpected outcome

Finally, Thomas takes a random roll of film from his lab and makes her believe that they are the photos taken in the park, after which she seems to gain confidence and become more compliant and participatory with his wishes. But everything changes abruptly when Jane notices what time it is and decides to leave quickly.

Thomas, motivated by the strangeness of everything that has happened, goes into the laboratory and begins to develop and print the photographs taken in the park. The sequence of the whole process is, frankly, masterful and not far removed from the rising suspense that Hitchcock created in his particular narrative process. Thomas, who to a certain extent is aware that there is something fishy going on, makes large copies of the photographs and hangs them around the studio, in the form of a photo-sequence, examining them carefully in search of something that, at first, he doesn’t quite understand.

Obfuscated by discovering something he can’t see

Obsessed with discovering what it is that he does not see in the images, he decides to enlarge specific areas of each photograph, after which he notices that in one of the shots in which Jane appears hugging her supposed lover, she is looking with a certain gravity in her expression towards a leafy part of the park enclosed by a fence. After enlarging the area several times, Thomas finally discovers, despite the lack of sharpness and the enormous film grain typical of enlarging such a specific part of the image, firstly a face in the undergrowth and finally the blurred and deformed silhouette of a hand holding a gun.

But Thomas’s foray through the images does not end there, for, desperate to go further, he looks at the photographs taken during Jane’s escape through the park and something else seems to catch his eye. After further enlargements, and even photographs of the same photographs, he discovers what is undoubtedly, despite the lack of definition, a human body lying on the ground. After that, he decides to return to the area where the events took place, now at night, and finally, the mystery is unravelled. In the undergrowth, the lifeless body of the man who had been playing with Jane in the park that morning still lies limp on the ground.

Can photography capture what the eye does not see?

This is undoubtedly what Blow-Up proposes, if we apply the logic that a photographic image contains much more information than that which has captured the interest that leads us to photograph something specific. Thomas meticulously rummages through the entrails of the image itself until he discovers what his eye did not see. Behind a supposedly banal scene of lovers in a park there was a whole parallel story of which Thomas was unaware and which, possibly, would have remained undiscovered had it not been for his suspicions and conviction that there was something more hidden in those photographs.

Can photography capture what the eye does not see? This is undoubtedly what Blow-Up proposes, if we apply the logic that a photographic image contains much more information than that which has captured the interest that leads us to photograph something specific. Thomas meticulously rummages through the entrails of the image itself until he discovers what his eye did not see.

Perhaps life is but a dream

But Antonioni, not content with such a lesson in the perception of reality, goes one step further in the final scene, when Thomas, after a night wandering around London, trying to find a way out of that discovery, which clearly ends up being a parable of the way out that he himself surely needs in his life. He decides to return to the park with his camera and discovers that the corpse has already disappeared. Dejected and confused, he approaches a group of young men with their faces painted like mimes, pretending to play tennis on a fenced court in the park. One of them pretends to throw a dummy ball across the fence, after which they gesture for Thomas to go to the spot and return it. Thomas walks over to a specific spot on the grass, picks up the imaginary ball and throws it back onto the court… The final shot, with Thomas gazing through the supposed movements of the match until he finally looks down at the ground while his facial expression is dramatised, is an open door to doubt… Perhaps life is nothing more than a dream…

Blow-Up is available via Google Play or the Qubit.tv platform.

Under fire. Observe or engage

Many of you will remember the recent case of the photograph of the boy Aylan Kurdi, who was found drowned on a Turkish beach in 2015 and who became an international symbol of the humanitarian crisis in Syria and the drama of immigration.

It is not the first time that a single photograph has altered the course of history, albeit temporarily. There are indisputable examples such as the photo of the Napalm Girl (Kim Phuc) taken by Nick Ut in 1972 or the street execution of an activist by a local Saigon policeman, captured by Eddie Adams in 1968.

It is not the first time that a single photograph has altered the course of history, albeit temporarily. There are indisputable examples such as the photo of the Napalm Girl (Kim Phuc) taken by Nick Ut in 1972 or the street execution of an activist by a local Saigon policeman, captured by Eddie Adams in 1968.

The press photographer

More than once in the cinema we have seen a character playing the role of a press photographer. But there are some films that have not only limited themselves to approaching this profession, but have also wanted to investigate the key role that some photographs played in the course of some of the most decisive events in history.

This is the case of the fantastic Flags of Our Fathers (Clint Eastwood 2006), based on the iconic photograph of American soldiers planting the US flag on Mount Subirachi at the end of the Second World War. Or the weaker The Bang Bang Club (Steven Silver 2010), which approaches the figure of the photographer Kevin Carter, who won the Pulitzer Prize with that extremely harsh and controversial image of the starving Sudanese boy lying face down while a vulture appears erect, behind him, a few metres away. A photograph that marked the high point of Carter’s career and may also have been the trigger for the personal crisis that led to his suicide a year later, at the age of just 33.

But there is a film that approaches, like few others, the world of journalism, and especially photographic journalism. And although it is fiction based on real events, it brilliantly delves into the role of photography in influencing and provoking change in the development of certain historical events. And it even dares to question aspects that have been much debated in recent years about the role of the press photographer, especially the war correspondent, as a mere observer of what is happening around him or her, or taking sides directly or indirectly for a cause through his or her work.

Under fire

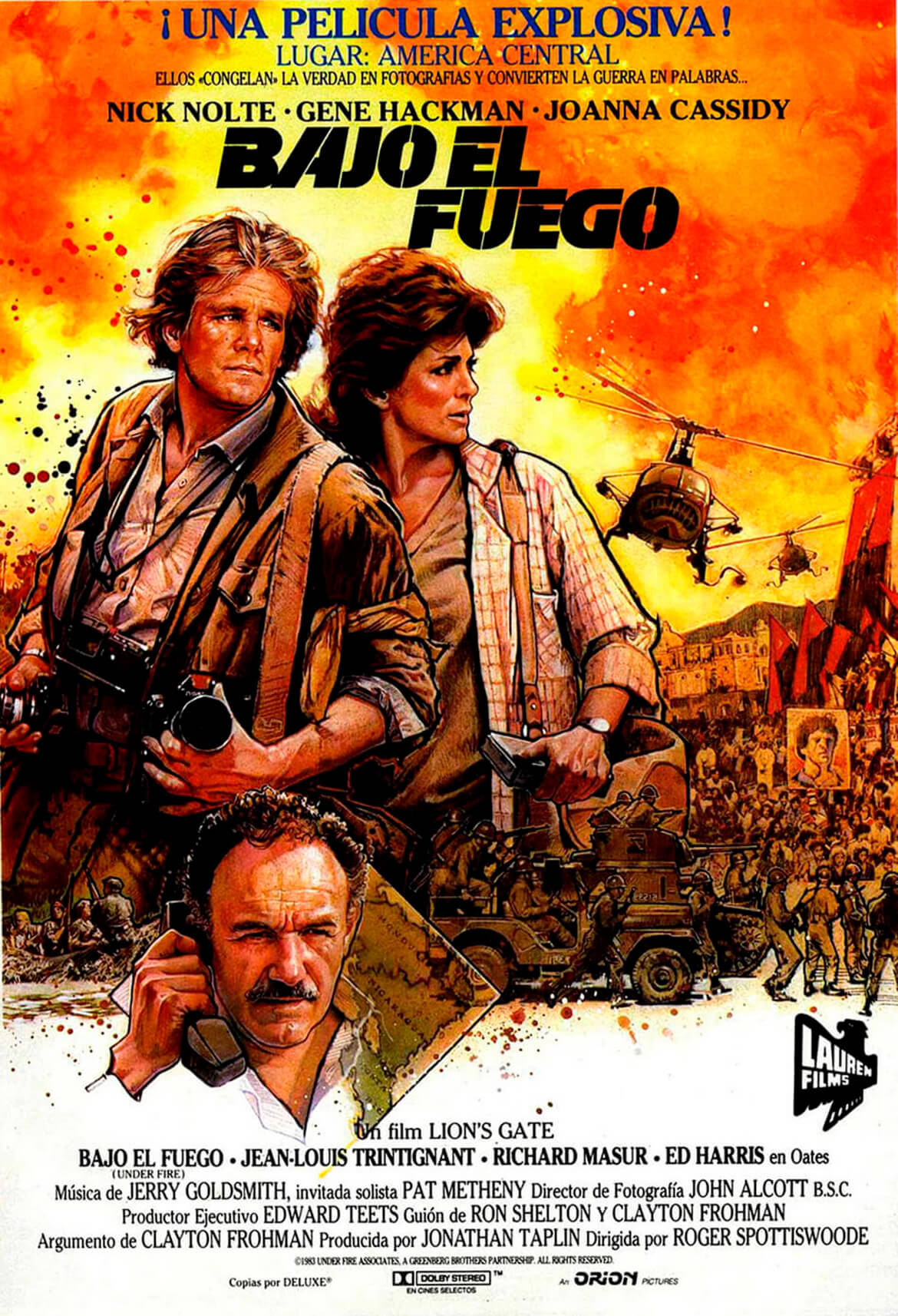

Under fire. A film directed by Roger Spottiswoode, who was Sam Peckinpah’s editor, and who reached his zenith as a director with this 1983 film.

It takes place in a real historical context, the last days of the dictatorial regime of Anastasio Somoza (son) in Nicaragua and the height of the Sandinista revolution, which was another of the many black spots on the US and its secret intelligence services (CIA), taking part in the proliferation of coups d’état and dictatorships throughout Latin America during the last century. This is something the film never shirks, being considered one of the most courageous political films of the 1980s, with the permission of the enormous Desaparecido (Costa-Gavras, 1982).

Three American journalists meet again in search of the news. On the one hand, Russell Price (Nick Nolte), a risk-taking, obsessive photojournalist, already experienced in different international conflicts and who follows Robert Capa’s famous quote “If your pictures aren’t good enough, it’s because you haven’t got close enough”.

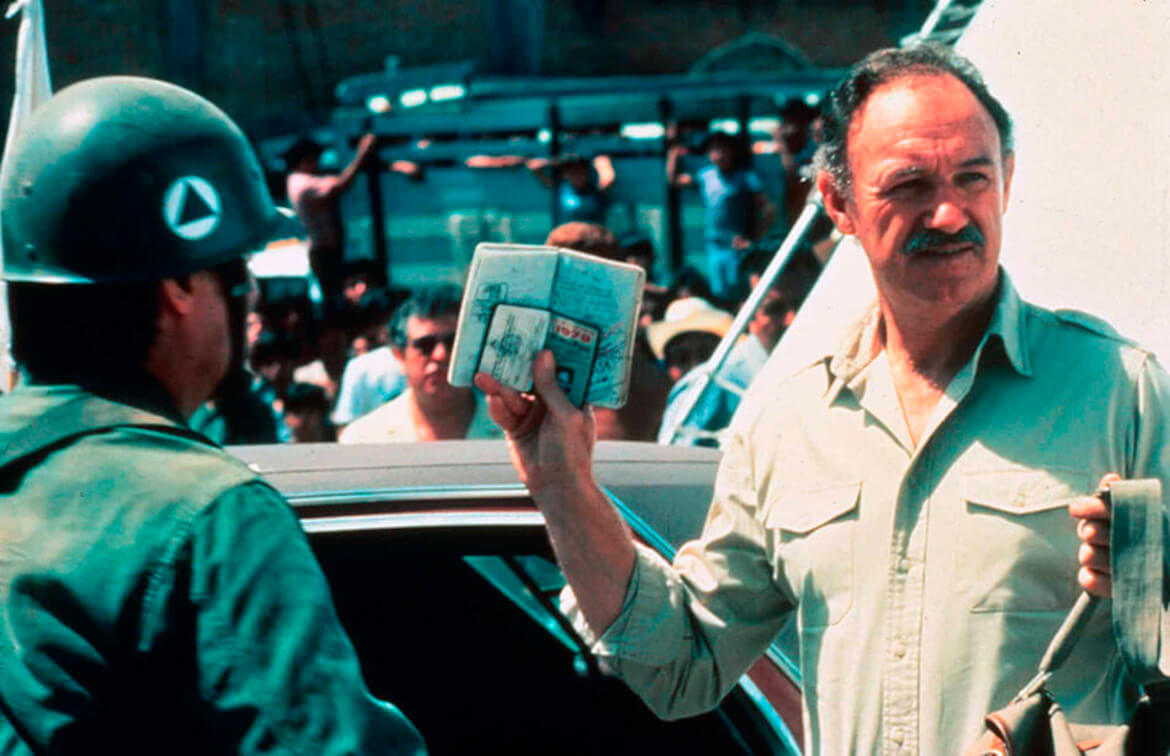

Alex Grazier (Gene Hackman), a veteran New York journalist, with a much less reckless character and somewhat exhausted from his constant travels around the world, is on the verge of a new professional stage as a news anchor at a powerful American TV network.

And finally, Claire (Joanna Cassidy), the link between the two, a brave reporter, committed to Grazier, but who will end up accompanying Price on his particular and redemptive journey that will lead them to become directly involved with the revolutionary cause by accepting the preparation of a fake photograph that will change everything in the Nicaraguan conflict.

Russell Price

Russell Price reaches a point in the film where he feels he has to take sides, disgusted by what he sees around him and the infamy with which the West permeates and conditions the situation. Excellently portrayed by the character of Oates (Ed Harris), a mercenary in the pay of the CIA with the mission of influencing international conflicts in the interests of the US administration, and the no less obscure and complex French spy Marcel Jazy (Jean-Louis Trintignant) who seems to act on several sides as the tide of events turns.

Price is presented with the opportunity to photograph the leader of the revolution, Rafael, a fictional character who could well be inspired by the former Sandinista leader, Daniel Ortega Saavedra. But what will be his surprise when, after being taken prisoner with Claire by the revolutionary soldiers and taken to the hidden place where the militias are hiding, he discovers that Rafael has been killed in a battle with Nicaraguan army troops and his body lies on a table in one of the rooms of the compound, still hidden from the rest of his compatriots.

The revolutionary leaders, who are aware of the facts, propose to Price to prepare a scene in which the dead leader appears to be alive and to take a photograph that will serve to silence the rumours of his death and reactivate a revolution that is not at its best. After debating with Claire about their profession and their role as journalists in so many conflicts, Price finally agrees to take the photograph that will end up reviving the hopes of those opposed to the Somoza regime, and the image becomes the new icon of the revolution.

The Nicaraguan conflict

But the story of Under Fire does not stop there, as there is a second plot after the photo of the leader Rafael that will further enhance the decisive role of photography in the resolution of the Nicaraguan conflict. After the photo taken by Price was reported in the international media. Alex Grazier, now a news anchor in New York, decided to return to Nicaragua under the auspices of the same TV station where he worked, with the intention of obtaining an exclusive interview with the Sandinista leader, turning to the author of the photograph and friend Russell Price.

Price, at first unable to tell him the truth, keeps up the lie until he and Claire finally decide to reveal that the Sandinista leader is dead and that the photograph was staged. Grazier is furious but finally decides to cash in on what happened and asks Price to help him locate the French spy Marcel Jazy as he does not want to return to the US empty-handed and without an interview.

Price agrees and together they embark on a car journey in the midst of a clearly warlike scenario, in which the Sandinista revolution is taking up more and more positions, provoking nervousness and excesses on the part of the pro-government forces. And it is precisely at a Nicaraguan army checkpoint where Alex Grazier is shot at point-blank range by one of the soldiers at the checkpoint, while Price, powerless to prevent it, witnesses the scene through his camera, managing to sequence Grazier’s murder in a burst of photographs.

The end of a conflict

Finally, the international dissemination of the images of the death of a Western journalist will, according to the film’s plot, provoke a clear change in the US position in the Nicaraguan conflict. The triumph of the Sandinista revolution and the fall of the dictator Somoza, who is finally exiled, with the financing of the US government, to Paraguay, are seen as inevitable. There, a year later, he died after being ambushed by a Sandinista commando in what is known as Operation Reptile.

(By the way, I don’t want to close this chapter dedicated to Under Fire without mentioning its spectacular soundtrack, by Jerry Goldsmith, with the great Pat Metheny on guitar. At the end of the post you have a couple of tracks from this soundtrack, performed by the City of Prague Philharmonic).

Bajo el fuego is available on the Filmin platform.

The public eye. The famous Weegee

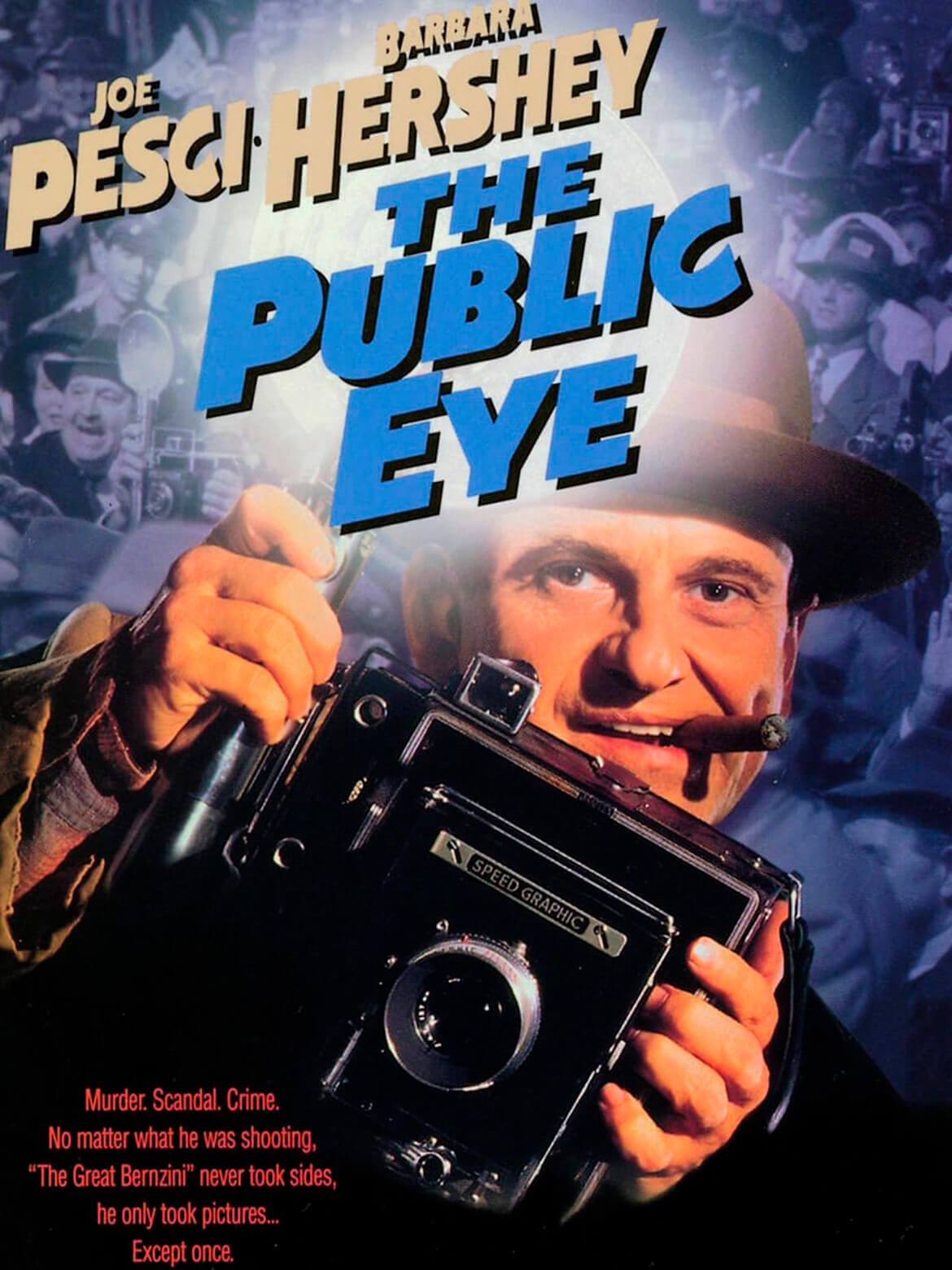

Another very interesting proposal is The Public Eye (Howard Franklin 1992) starring an immeasurable Joe Pesci, who at that time gave us some of his best performances in films such as One of Us (Martin Scorsese 1991), for which he won the Oscar for best supporting actor. Or Casino (Martin Scorsese 1995), another of my favourite films, in which he gave life to one of the most cynical and savage gangsters in the history of cinema: Nicky Santoro.

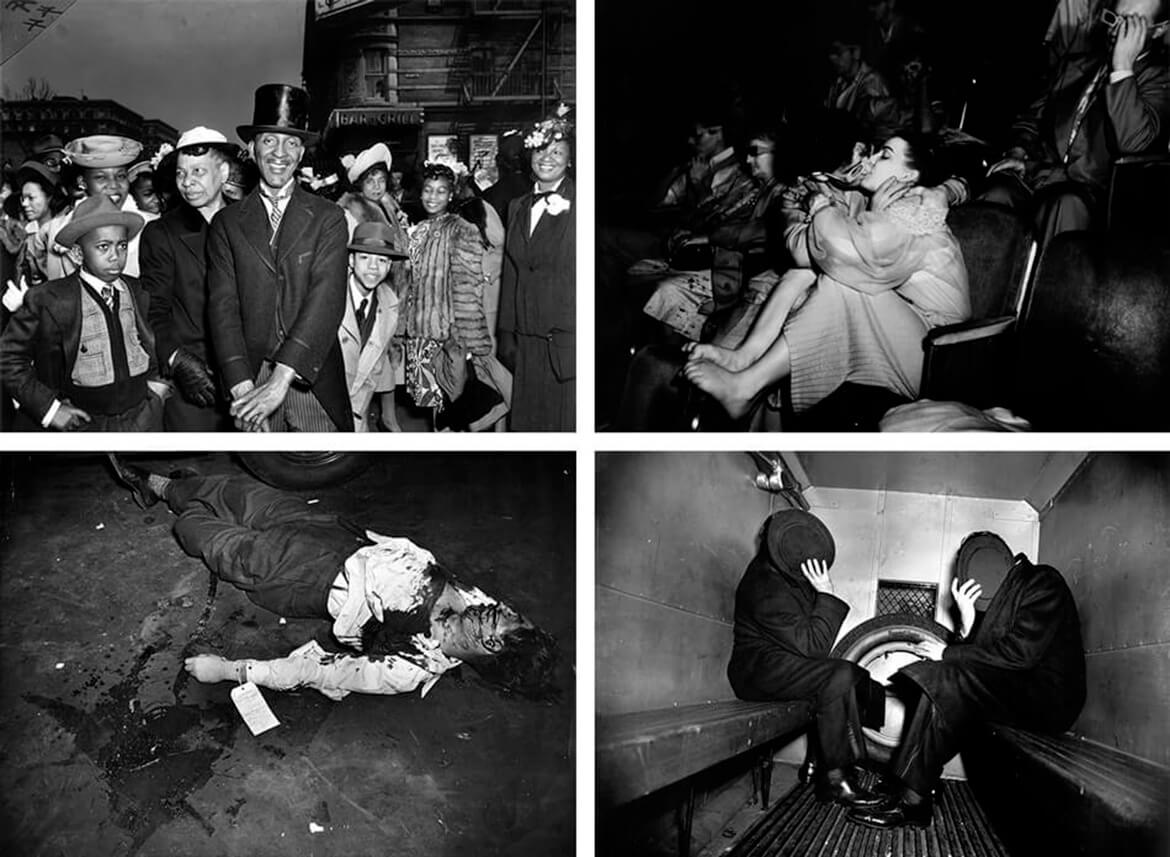

But in The Public Eye, Pesci plays Leon “Bernzy” Bernstein, a character who, although fictional, is clearly inspired by the life and work of one of the most peculiar documentary photographers in the history of photography, and the author of some of the most shocking and well-known images of events in the turbulent New York of the mid-20th century.

We are talking about Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee. In fact, much of the photographic material in the film is from Weegee’s original work, and without a doubt, Pesci’s choice could not have been more appropriate, as the physical resemblance between the two is astonishing. His performance is so brilliant, that at some points you come to think that he is Weegee himself reincarnated.

Classic film noir

Although the film has a supposedly fictitious plot in a carefully crafted classic film noir format, I recommend that you soak up Weegee’s story and images before watching it. Because this will make you enjoy it even more, as many of the eccentricities of the character and his particular modus operandi as a photographer are taken from Weegee’s real life, who is said to have no qualms about altering the scene of a crime if it didn’t quite fit the shot.

Weegee was born Usher Fellig in the Ukraine in 1899, later changing his name to Arthur Fellig, after emigrating with his family to the United States when he was only 10 years old and settling in New York. After a difficult childhood and adolescence in which he was forced to abandon his basic studies in order to work and even lived as a pauper, in 1918 he began to photograph the streets of New York and, despite having no training as a photographer, got a job as an assistant in a photographic studio, after which he worked as a photographer for various agencies.

But if there was one thing Weegee had, apart from his lack of qualms about firing his camera and flash, whatever the situation, even inside a dark cinema to capture a loving couple making out between the seats, it was his ability to sell and promote himself, going so far as to sign his photographs with a, by no means modest name, photograph of the famous Weegee.

New York’s nightlife

In 1935, Weegee set up as a freelance photographer and began to delve into New York nightlife, loaded down with a bulky 4×5 Speed Graphic. The quintessential camera of the New York press of the time, to which must be added the flash, whose bulb had to be changed after each shot.

But if there was one thing Weegee had, apart from his lack of qualms about shooting his camera, even inside a dark cinema to capture a couple in love making out between the seats, it was his ability to sell and promote himself, going so far as to sign his photographs with an unassuming Weegee photograph. It was his ability to sell and promote himself, even going so far as to sign his photographs with a, by no means modest name, photograph of the famous Weegee.

In fact, his reputation as a photographer and his ability to make interested contacts and friendships was such that in 1938 he obtained special permission to install a radio in his car directly connected to the frequency on which the New York police operated, arriving at the scene of the crime even earlier than any other officer and, of course, any other journalist.

The most widespread theory about the origin of the pseudonym Weegee is that it refers to its phonetic similarity to the word ouija board, in relation to his ability to be the first to arrive on all stages. It is precisely this peculiarity of his way of working that gives rise to one of the most empathetic scenes with Weegee’s alter ego, played by Joe Pesci, when his mentor and friend asks him how to turn off the “damn” car radio and he replies, with a distressed gesture, that there is no way to disconnect it.

The first to make the images

But Weegee was not only able to get anywhere before anyone else. He was also always the first to get his exclusive images to the newspapers before they closed the next day’s edition and put the presses to press. Leaving the rest of his colleagues on the sidelines, for whom it was impossible to compete with such a gift of “ubiquity”.

Weegee took the idea of turning his car into his own home to such an extent that he had a complete chemical photographic laboratory in the boot of the vehicle, with which he did not hesitate to hide in the darkest alleys of New York to develop and print the photographs taken a few minutes earlier, even delivering some of these images to the newspaper, not only “fresh”, but completely wet.

Although many have dismissed Weegee’s work as sensationalist, no one can deny that he managed to stamp his images with a particular stamp, precisely because of his use of powerful flash light and the contrast between light and shadow in his images, which further accentuated the drama of the subject matter.

But to label Weegee solely as a photographer of events would be an understatement to understand the magnitude of his work. Weegee was also a formidable visual chronicler of the city that never sleeps. His photographs, beyond the most lurid and violent motifs, are populated by an innumerable catalogue of characters drawn from that nocturnal, grotesque and even surreal habitat that was the “mean streets” of the New York of the 1930s and 1940s.

The public eye

All these aspects of the character are captured in The Public Eye, through Bernzy, the recreation of Weegee played masterfully by Joe Pesci in the film.

There is a subplot that captures the photographer’s obsession with notoriety and public recognition when we see the character make a strange wheeled contraption that he then incorporates into the base of a small camera. At the time you don’t quite understand the fate of such a mechanical device until later, despite the implausibility (or not) of the resolution of the enigma, you are fascinated by the moment.

Bernzy has managed to discover the location of a massacre between rival New York mafia families, giving him the opportunity not only to photograph the scene of a spectacular crime, but also to capture with his camera the precise moment when it is executed. And it is in the chaos and violence of the shooting that Bernzy, who for the previous minutes has remained hidden without anyone detecting him, emerges from the shadows with his Speed Graphic and its powerful flash and begins his particular photographic shootout, amidst bullets, splinters and bodies flying through the air, launched by the power of the machine-gun fire.

And in the midst of such a hecatomb, he still has the cold blood to activate the mechanism created for the occasion, and that is when we see how the small camera fitted with wheels runs across the floor of the room amidst the chaos, and after a time interval, the timer on it activates the shutter and captures the snapshot of Bernzy himself taking photos of the massacre. Undoubtedly the most bizarre selfie in the history of cinema.

The public eye is available on Google Play.

There are films that went somewhat unnoticed at the time but which have acquired a certain relevance over time. More than for the quality of the films themselves, it is because, when they are revisited now in the current cultural and social context, one cannot help but see in them a certain anticipation of what came years after their production.

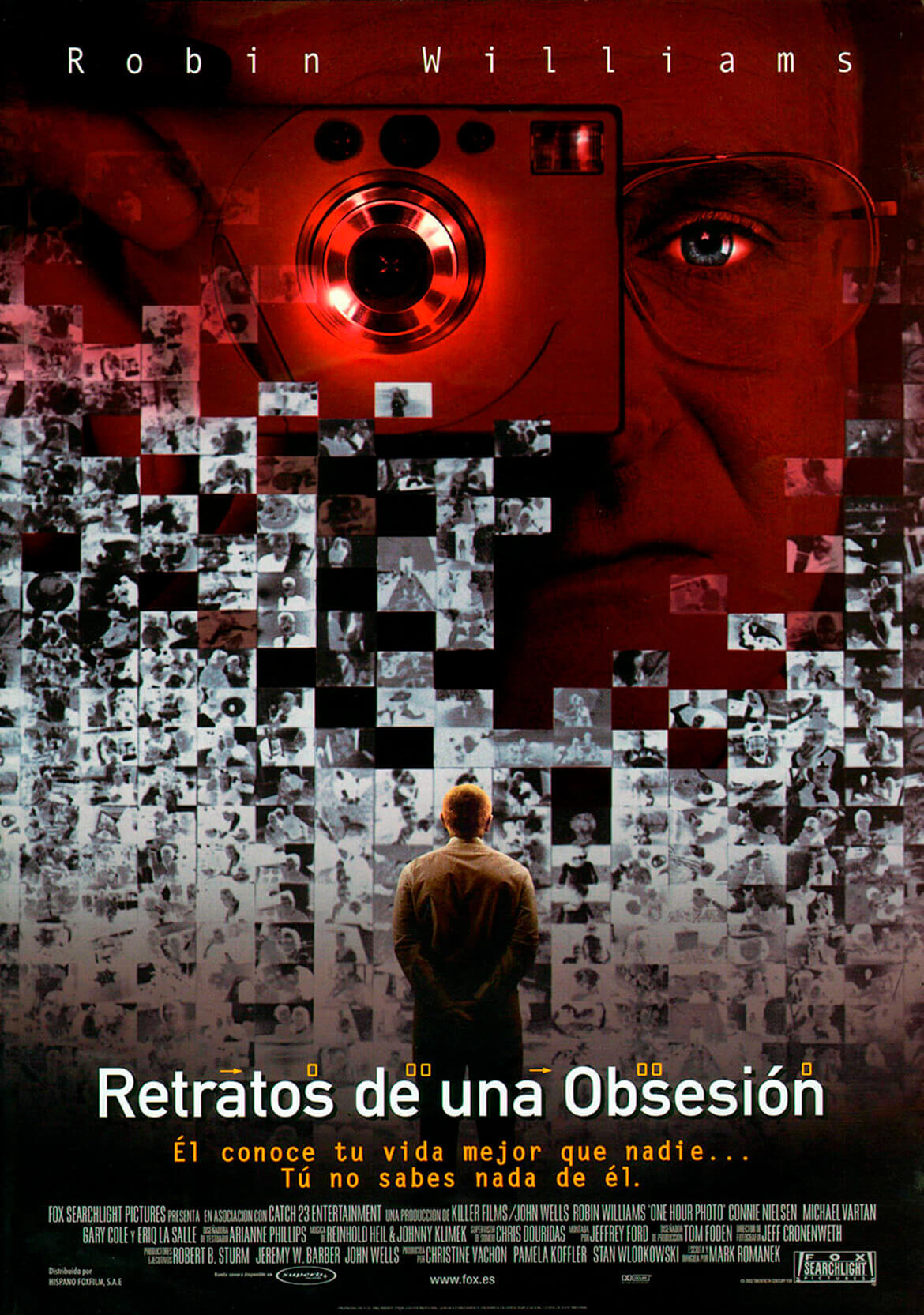

And we are not talking about a film that is very distant in time, because One Hour Photo (Mark Romanek) was released in 2002, a few years before the irruption of Facebook that brought with it the era of social networks and what will happen to you morena. And the fact is that, although it may seem incredible to many, in 2002 we were not yet ‘selling’ our lives (and data) compulsively through the Internet, and analogue photography still reigned, although it had little time left to be dethroned by digital, which was approaching at the speed of a howitzer.

In the early years of this 21st century, we were still taking our domestic photos to be developed in a specialised shop or in the 1-hour development services (remember?). In fact, the original title of this film is One Hour Photo, much less sensationalist than the English title.

One Hour Photo

In One Hour Photo, Robin Williams, who at the time wanted to give a twist to his typecast (and hard-won) role as a comedy actor, playing a couple of psychopaths in films (he would repeat the experience the same year in Christopher Nolan’s interesting Insomnia). He plays Seymour “Sy” Parris, a lonely, introverted clerk at a developing shop in a suburban Los Angeles supermarket, who develops a closer relationship with some customers, the Yorkins. A typical bourgeois American family, young and modern, who seem to exude happiness and perfection from all sides.

This relationship, which, as a rule, never goes beyond the stand from which Sy scrupulously attends to his clients, ends up becoming an obsession for him, who sees in the Yorkin family a perfection and a social status to which he undoubtedly wishes to aspire and be a part of.

But the interesting thing about One Hour Photo is that this perception of happiness and good feeling comes to Seymour, not especially in his dealings with the Yorkins, which are initially affable but do not go beyond the limits of cordiality, but through the photographs that they, and above all Jake, the youngest of the family, have been taking to be developed for years at the establishment where our protagonist works.

And it is that the “good” Seymour, not only limits himself to snooping in other people’s images, but, in the case of the Yorkin, he does not hesitate to take two copies of each photograph, one for delivery to his clients, and another for himself.

Seymour and the Yorkins

Seymour’s fixation with the Yorkins grows, reaching a point where he is no longer content simply to invade their privacy through his photographs, but also feels the desire to be part of their pristine and perfect ecosystem in some way. And the way in which the film resolves this aspect is curious, when the Yorkins take their photos to be developed without having completely finished the film and Seymour does not hesitate to photograph himself until the roll is finished and add these photographs to the paper copies delivered, as if he were another member of the family being photographed. This does not go unnoticed by the Yorkins, who begin to empathise with Sy, for whom they begin to feel a certain pity in seeing him as someone sad and lonely.

But things get twisted, if they weren’t twisted enough before, when Sy discovers, during one of his precise developing processes (at times he looks more like a scientist in gloves and a lab coat than a supermarket employee), some photographs that reveal the affair that William, the supposedly perfect father of the Yorkins, is having with his mistress. An act he interprets as a personal betrayal, since in his complex state of mind, Sy feels he is an undisputed member of his particular “adoptive family”.

A psychopath out of control

It is from here, unfortunately, that the plot of the film moves away from the interesting starting point and into a predictable tale of an out-of-control psychopath, with childhood trauma included that justifies everything. It manages to maintain interest thanks to the film’s carefully crafted visual finish and, above all, Robin Williams’ restrained and disturbing performance.

Plot solution aside, Portraits of an Obsession offers an interesting premonitory reflection on photography in the times we live in today.

Plot solution aside, One Hour Photo offers an interesting premonitory reflection on photography in the times we live in today. And the fact is that this proliferation of perfect lives, selfies brimming with happiness and profile pictures in which one never looks bad is part, 18 years after the film’s release, of everything we digest daily through the images published on social networks. With the difference that now there is no need to be a voyeur who secretly spies on the lives of others through their photographs, as we have reached the point of normalising the fact that we ourselves are the ones who publish and “sell” our supposedly “perfect life” on Instagram or Facebook. Making not only our acquaintances, but also others with whom we have never had any dealings in life beyond a screen, participants in our intimacy (the real and the prefabricated).

But just as Sy discovers that the family he feels part of is not as perfect as it seems, taking for granted that this subjective world born and nurtured on social networks is a reliable reflection of reality can lead us into a misperception and misinterpretation. Not only of the lives of others, but above all of ourselves if we end up believing ourselves to be the avatar behind which we hide, or think we hide.

It is disturbing to what extent, in one of the best scenes of One Hour Photo, from a still analogue photographic world, he manages to predict certain aspects of our current visual (and social) culture. Especially when he shows us Sy at home, alone, sitting in the middle of a room that makes up his particular feed, with hundreds and hundreds of images of his idolised Yorkin wallpapering a wall as if it were the perfect Instagram grid.

Portraits of an Obsession is available via Apple TV.

@bernatgu and photography as seen by cinema.

A couple of music for this post:

Arcadina goes with you

Fulfil your dreams and develop your career with us. We offer you to try our web service free for 14 days. And with no commitment of permanence.

Arcadina is much more than a website, it is business solutions for photographers.

If you have any queries, our Customer Service Team is always ready to help you 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. We listen to you.