Photography in the times of the #fotografi@ (part one)

For many of us who have still touched analogue photography, processing all that has been involved in the convulsive road to this digital era, exhausting in many respects, has left a somewhat bittersweet taste in our mouths.

Sweet, no doubt, because of all the creative possibilities that technology has brought with it, and bitter, too, because, as the photographer Siqui Sánchez defined five years ago in that legendary piss-up, Apotheosis of Shitdography, when an artisan activity (because that is what we photographers were: artisans of the image) becomes a fast food product, the essence of that artisan act ends up being swallowed up by trivialisation and the absence of that intellectual complexity in the discourse, which is necessary in any creative or artistic process.

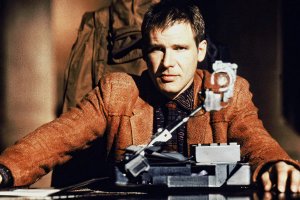

Harvey Keitel in one of the iconic scenes of Smoke (Wayne Wang 1995)

Contenido

Photography is not dead, it has evolved

Photography is not dead, it has evolved, and in what a way, but it must be recognised that since it has become “democratised”, its use in social networks has something of, and I quote Siqui again, “behavioural pathology”.

And now comes the warning for navigators. Photography revealed to me one of the pillars of my beliefs, and that is that objectivity does not exist, although pretending or aspiring to it are very laudable attitudes. I am one of those who believe that the act of photography is a totally subjective act, and the same concept applies to my perception of things, even when they do not pass through a camera. Therefore, what I write here is nothing more than the fruit of my own Instagram filters.

Photography revealed to me one of the pillars of my beliefs, and that is that objectivity does not exist, although pretending or aspiring to it are very laudable attitudes.

30 autumns photographing

In my case, the analogue years and the (exclusively) digital years are now almost on a par, and together they add up to 30 autumns. I am not one of those who miss analogue, at least as far as image production processes are concerned, as it would be absurd to deny all that my conversion to digital has brought me, creatively and, above all, professionally since I first entered the subject in 1998, not only in the field of photography, but also in design (my other passion).

But I recognise, as a good experienced nostalgic, that sometimes, when I close my eyes and mentally transport myself to my first black and white years and relive the sensations of that photographic era, I feel a mood of complacency close to an overdose of Calm, that app that aspires to replace the consumption of valerian.

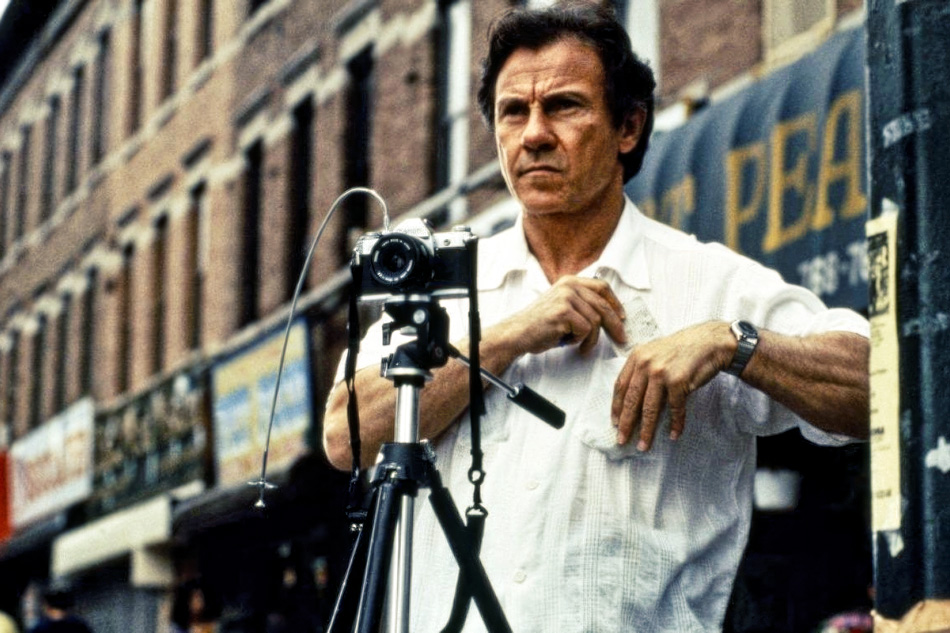

I suppose that, although I don’t miss the technical processes, I do miss the essence of the photographic act at the time, that of the observer carrying a camera and capturing interested fragments of what he sees, with which to create a visual discourse that, in many ways, in my case, was closer to the “inner world” than to any interest in showing the outside world from a realistic point of view.

Selfie among the stars (fragment). © Bernat Gutiérrez 2018

Because, dear millenials. There was a time not so long ago, in a galaxy not so far away, when megapixels didn’t exist in our lives, and Photoshop (this one did exist, I’m not that old either) was something that four luminaries handled and sounded like the onomatopoeia of a belly flopping in a pool full of water.

Photography used to be no different than it is now

Photography wasn’t very different from what it is now, it was just that, back then, instead of capturing the image through sensors, we did it with rolls of photosensitive film. No LCD screens or silent mirrorless cameras; seeing the photo instantly was good science fiction (except for the Polaroid guys). And I swear I have even woken my father from his nap, in heart attack mode, with the click-clack of a medium format camera.

Because, dear millenials, there was a time not so long ago, in a galaxy not so far away, when megapixels didn’t exist in our lives, and Photoshop (it did exist, I’m not that old either) was something that four luminaries handled and sounded like the onomatopoeia of a belly flopping in a pool full of water.

Development, yes, it has evolved

Developing, now that’s evolved (holy cow!). Back then, the process of obtaining an image after it had been captured in camera was something, to say the least, rather damp and halfway between absolute darkness and the red light of a whorehouse in the cinematographic imagination.

For one thing, removing the film from a 35mm metal reel and inserting it into the spiral of the negative development tank had its paraphernalia, as this could only be done in total darkness (the negative was sensitive to all kinds of light), with dexterity in your hands and using the latest technology of the time, such as a bottle cap opener.

Fortunately, once the watertight tank was loaded, you could continue the process with the lights on, although I know of some who did not understand the methodology properly at the beginning and continued with the lights off until they took the developed negative… “It was an agonising 20 minutes”, one confessed to me.

Funny Face (Stanley Donen 1957)

Nothing more and nothing less than a chemical process

Yes, the process was chemical and consisted of a combination of times when the photographic support came into contact with water and small doses of 4 products that we called developer, stop bath, fixer and wetting agent.

We felt like scientists with our test tubes, our cuvettes with clamps, our timers to control the time of use of each liquid, our white coats… Well, the white coat was not necessary, but I admit that it gave one a certain air of respectability, even if the ideal working place, when you had no infrastructure, was the toilet of your house, with the window covered with black cardboard, and the space illuminated in garish red, to which the photographic paper (in black and white) was not sensitive during the printing process.

Seeing for the first time how a photo was emerging, as if by magic, on a paper submerged in liquid, amazed more than one, provoking a Stendhal Syndrome, although in many cases it was found that they had previously sucked, with force, in the bottle of the concentrated stop bath (those of you who know this know what I’m talking about). Laugh at Lightroom now.

Seeing for the first time how a photo emerged, as if by magic, on a piece of paper immersed in liquid, amazed more than one person, provoking a Stendhal Syndrome.

The evolution of photography in just over 20 years

Xennial xennial foppishness aside, and without going (for now) into more details about how these things were done not so long ago, the evolution of photography at a technological level, in little more than 20 years, is truly vertiginous if we compare it with the evolution during its 2 centuries of existence, year up, year down.

We are currently experiencing a veritable “fury of images”, as the great Joan Fontcuberta described so well, who, by the way, is the true architect of the word fotografi@, although I have allowed myself the licence to add the hashtag to it.

Many photography professionals have adapted to these changes, some reluctantly and others, as in my case, because we are real sponges eager to continue evolving. We live this fury with contradictory sensations.

On the one hand, with the expectation that technological advances have been contributing to this sort of creative infinity that has been presented to us as an almost endless accumulation of professional and artistic possibilities. And on the other hand, with the feeling that this massification of images and of capturers/producers/creators of these, together with an unleashed market of photographic products whose advances are already bordering on the obsessive (to see who can make the most enormous device), is nothing more than the prelude to a bubble that will end up, in truth, killing successful photography.

The education of the photographic eye

It is one thing to be a photographer and quite another to educate the photographic eye. Photography has never been simply a matter of pressing a button, nor is it now the exclusive preserve of networks such as Instagram or Photoshop as if there were no tomorrow. Photography goes beyond technical aspects and to understand it in its full dimension we cannot ignore the creative, social, cultural and, much less, those intrinsic to the condition of the 21st century photographer, not only as an observer, but also as a generator, creator, producer and manipulator of images.

Smoke (Wayne Wang 1995)

Arcadina has given me, through its blog, the opportunity to share with you not only experiences and perspectives, but also a necessary debate, not devoid of edges. About the past, the present, and the future of one of the most fascinating creative fields in existence, whose presence and influence in society goes far beyond the screen of a smartphone.

To be continued…

Music for this post:

Headache for your photography business? Take an Arcadina

Headache for your photography business? Take an Arcadina

Fulfil your dream of becoming a professional photographer with the help of our business solutions. Now you can create a website and business for free for 14 days with no commitment of permanence.

Thanks to Arcadina’s business solutions for photographers, your business headaches will disappear.

If you have any queries, our Customer Service Team is always ready to help you 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. We listen to you.