Selfie

There is a debate on the Internet about the authorship of the first “selfie in history” (inverted commas, please) and the time frame in which it was taken. The debate, beyond breaking some millennial’s mind by placing the first action attributable to the Anglo-Saxon term selfie outside the 21st century and without an upload option on Instagram, involves another secondary debate (or perhaps it is the main one) about the correct definition of what a selfie is supposed to be.

Contenido

- The Byron Company selfie

- The pioneer

- Shall we take a selfie? Of course we can, guapi

- The self-portrait, then…

- Influencers

- Beyond the fourth wall

- Bonus Track

- Arcadina goes with you

- Robert Capa: the "American" who was there

- Photography in the times of the #photogr@phy (second part)

- The profession of photographer is not valued and these are the 6 main reasons for this

The Byron Company selfie

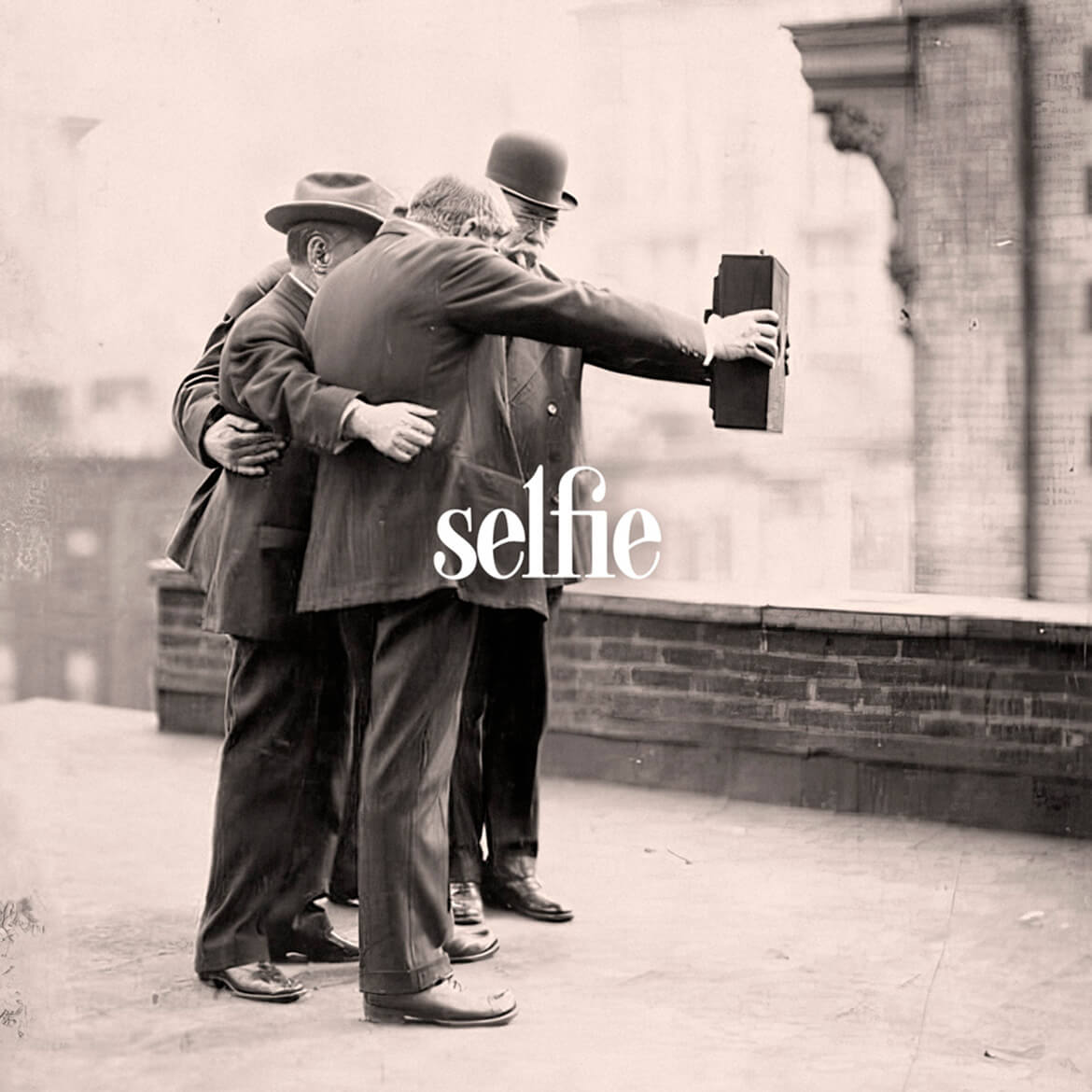

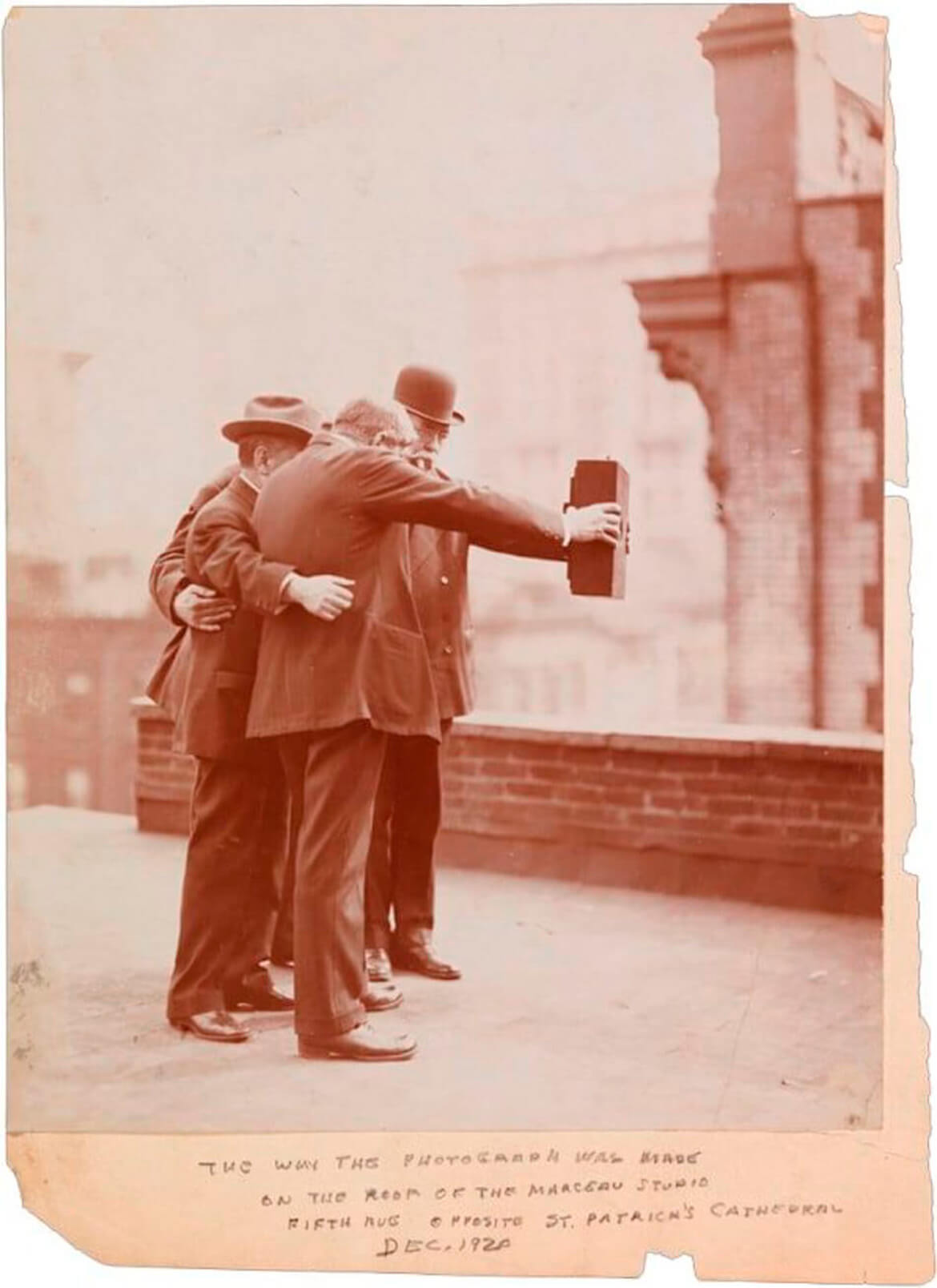

The best known story, and possibly the one most consistent with the current term, is that of the Byron Company photographers. These photographers, in December 1920, supposedly took a group selfie on a rooftop in New York holding a camera in their hand with the lens pointed at themselves. Just as we do today with any smartphone, but with the difference that they fit in the palm of one hand (some of them) and the camera used then was a much larger and more rudimentary device.

The alleged ‘first selfie in history’, taken by Joseph Byron and his team at the Byron Company in 1920.

It is certainly not the photo itself, taken by the selfie camera, that gives this event a special relevance, but rather another photograph taken from a side angle in which the protagonists can be seen in the midst of their work.

This scene could also be considered the first “making of history” of a selfie. This second image is the one that complements and fills with transcendence what happened on that Manhattan rooftop in the 1920s. It shows, from a different perspective, how the selfie came about. Surely, without the protagonists being aware of being in front of a moment that would acquire such a relevant dimension 100 years later in a society with no more historical memory than what happened in a single era: that of social networks.

Making of the first selfie in history.

Making of the first selfie in history

These two photographs, together with another self-portrait of Joseph Byron himself (the one with the bowler hat in the foreground), photographer and founder of the Byron Company, which he took in the same way and which some even date to earlier years, are now in the Museum of the City of New York.

The pioneer

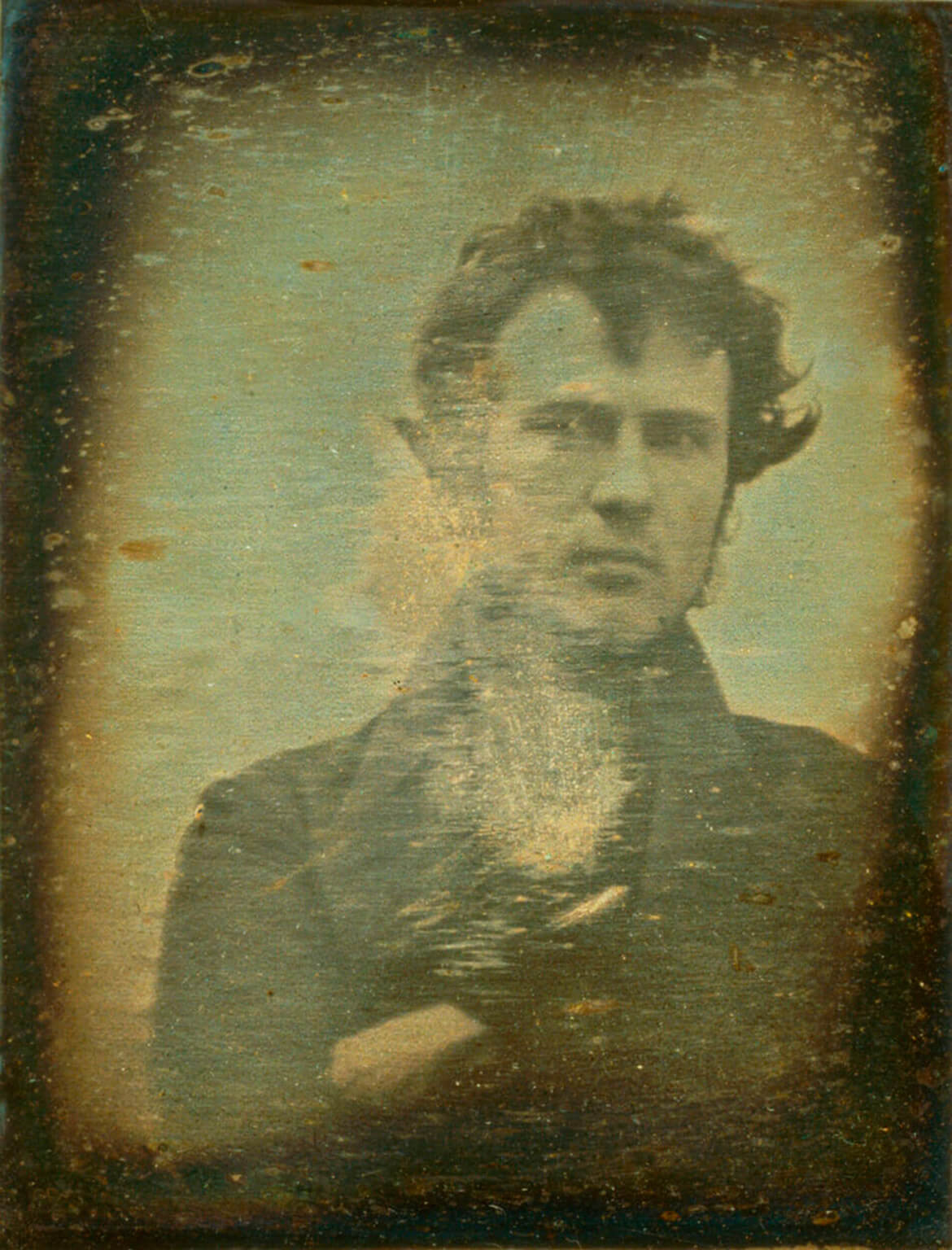

The other story in question is that of photographic pioneer Robert Cornelius and an image now jealously guarded by the US Library of Congress.

It is a self-portrait taken in 1839 (81 years before the Byron Company’s selfie), possibly taken with a dark box of his own making. This image was certainly not the first attempt at a time when photography was still a fledgling technique. It should be borne in mind that the processes for obtaining a photograph on a physical support (daguerreotype) were closer to scientific research than to the photographic act as we conceive it today, in any of its representations.

But the fact is, and here lies the controversy, that Robert Cornelius’s selfie, unlike that of Joseph Byron and his contemporaries, was not taken holding the same camera with the lens pointed at oneself. Rather, it is an image obtained through the reflection of the subject in a mirror. To take this photograph, poor Cornelius had to remain unperturbed for 15 minutes due to the mechanism and exposure process of a dark box of the time.

Self-portrait of Robert Cornelius taken in 1839.

The first selfie in history

Currently, both the Byron Company’s photo and that of Robert Cornelius are competing on the Internet for the honour of being the first selfie in history. But perhaps, before reaching any conclusion, we should discuss what the concepts of selfie, selfie and self-portrait are and what they have (or do not have) in common. This debate is not as complicated as it seems, and the conclusion probably depends more on the interpretation of each word in popular culture than on establishing clear differences that delimit the use of each term.

We could say that both images are self-portraits, if we consider the fact of taking a photo of oneself. Moreover, there would be no doubt that the 2 photographs are also self-portraits.

A self-portrait was, without a doubt, the most common definition among photographers to describe this type of photographic pieces until the Internet made us so cool (briefing, branding, smoothie, coaching, feedback, trending topic… camonbeibelaikmayfalla…). But… are the 2 photos really a selfie?

Shall we take a selfie? Of course we can, guapi

If memory serves me correctly, it won’t be 10 years since I first heard this Anglo-Saxon word. At first I didn’t pay much attention to it, but it’s true that, as its use began to spread to describe the act of taking a selfie with a mobile phone, it started to touch me a bit on the soft underbelly.

All our lives we’ve been talking about ‘self-portrait’ to describe the act of taking a photograph of oneself and all of a sudden the latest trend in modernity is “shall we take a selfie? “Of course we can, beautiful!”

I even became vindictive and tried to eliminate any temptation to include the word selfie in my everyday vocabulary, until one day it was me who picked up his mobile phone and said, “Come on… shall we take a self-portrait? “. And after seeing the resulting photo, I was shocked to see the faces of the four people behind me because I thought they had all suffered a stroke at the same time.

And it is from this daily observatory in which you see how people’s habits and customs evolve, where it is not difficult to reach the conclusion that: a self-portrait is any image obtained or generated of oneself, whatever the technique.

With time, one becomes more flexible, especially if one observes one’s surroundings from an equidistant position before any judgement is made (another accursed word…). And it is from this daily observatory that you see how people’s habits and customs evolve.

What is a self-portrait?

At that point, it is not difficult to come to the conclusion that a self-portrait is any image obtained or generated of oneself. Whatever the technique used. And a selfie has the particularity that, being also a self-portrait, it has been obtained by holding the photographic device oneself, either by hand or through such practical inventions as a selfie stick with the lens pointing directly at the photographed self.

And this is when you say “You see, so much history to come to this”.

Well, the apparent simplicity of this conclusion is even more disturbing than everything I have told you so far in this article. Because in the end it corroborates one of the historical anecdotes put forward, but calls into question the other for not fitting the term correctly.

What is the first selfie in history?

If the question posed on the Internet is: what is the first selfie in history? Without a doubt, the correct choice is the famous selfie of the Byron Company (if no previous image with the same procedure is confirmed). This photo is the one that fits today’s conception of what a selfie is: a photographic self-portrait taken while holding the camera towards oneself.

The image of Robert Cornelius is therefore procedurally ruled out. At least he will have the honour of being considered the first self-portrait in history. Another of the attributions on the subject that swarm the Internet.

Yes? Are you sure? Let’s see.

From left to right: Self-portrait with cap and two chains by Rembrandt (1642-1643). Self-portrait by Goya (1815). La Meninas by Velázquez (1656) with Velázquez himself portrayed on the left of the painting.

Self-portrait outside photography

Well, it seems to me that poor Cornelius is not going to be the protagonist and author of the first self-portrait in history either, because if we were to consider him as such, we would be overlooking centuries and centuries in which the self-portrait has been a plastic exercise that has been used with total normality from artistic techniques much more widespread and practised over time than photography itself.

If it weren’t for that tendency to create headlines for quick consumption and that other tendency to “gobble up” content on the Internet at the speed of a tweet (which will have made more than one of us abandon this reading before the second paragraph). Everything would have been fairer for Robert Cornelius, who despite the fact that his photograph can by no means be considered the first self-portrait in history. He does have the honour, no less important, of being the creator of the first photographic self-portrait in history.

The self-portrait, then…

The self-portrait (and now let’s get down to business), differs from the selfie in other aspects of much greater significance than the mere process of obtaining the image.

And the fact is that the use of the selfie is currently more of a passing fad and behavioural pathology and – does anyone doubt it – quite a bit of narcissism.

Whereas the self-portrait, throughout the history of art, has always been linked to a creative and experimental discourse in which the author himself, in a clearly introspective act, (re)discovers or (re)defines himself through the recreation of his own image. As a general rule, the representation manifests itself with the same discourse, style and technique with which it does so in the rest of his artistic work.

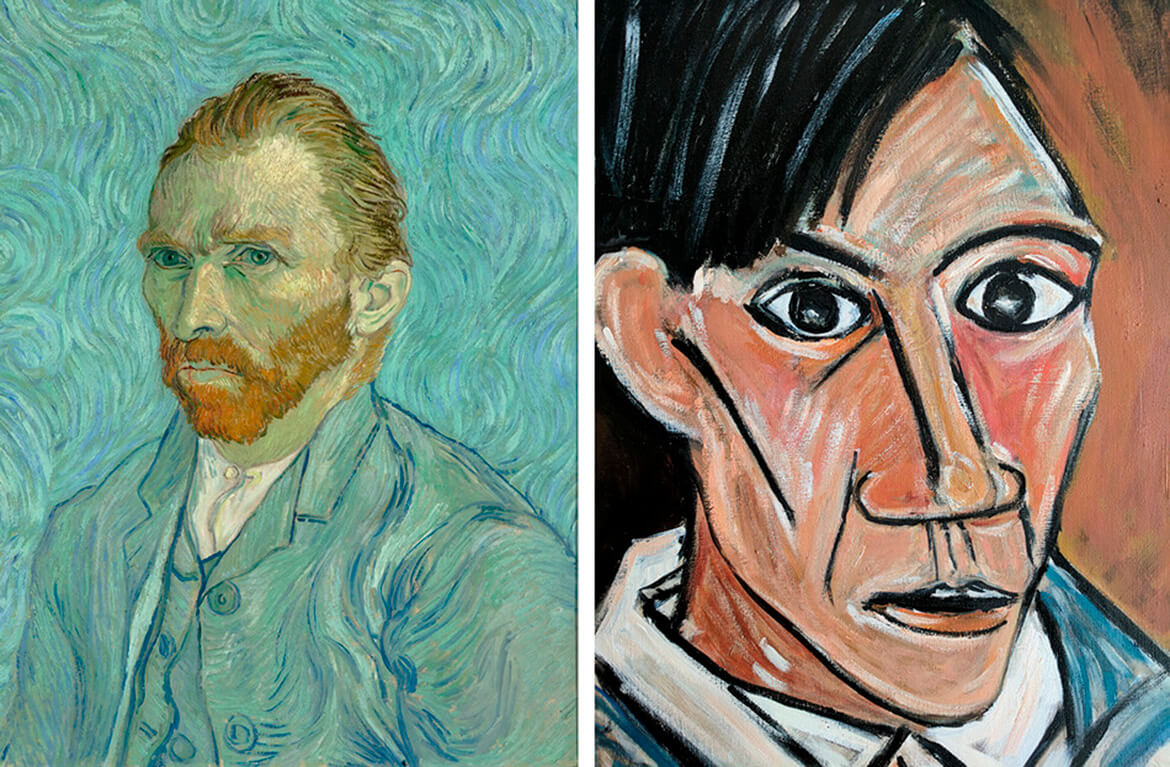

From left to right: Self-portrait of Van Gogh (1889). Self-portrait by Picasso (1907). Self-portrait with spherical mirror by M.C. Escher (1935). Self-portrait by Frida Kahlo (1940).

My self-portrait

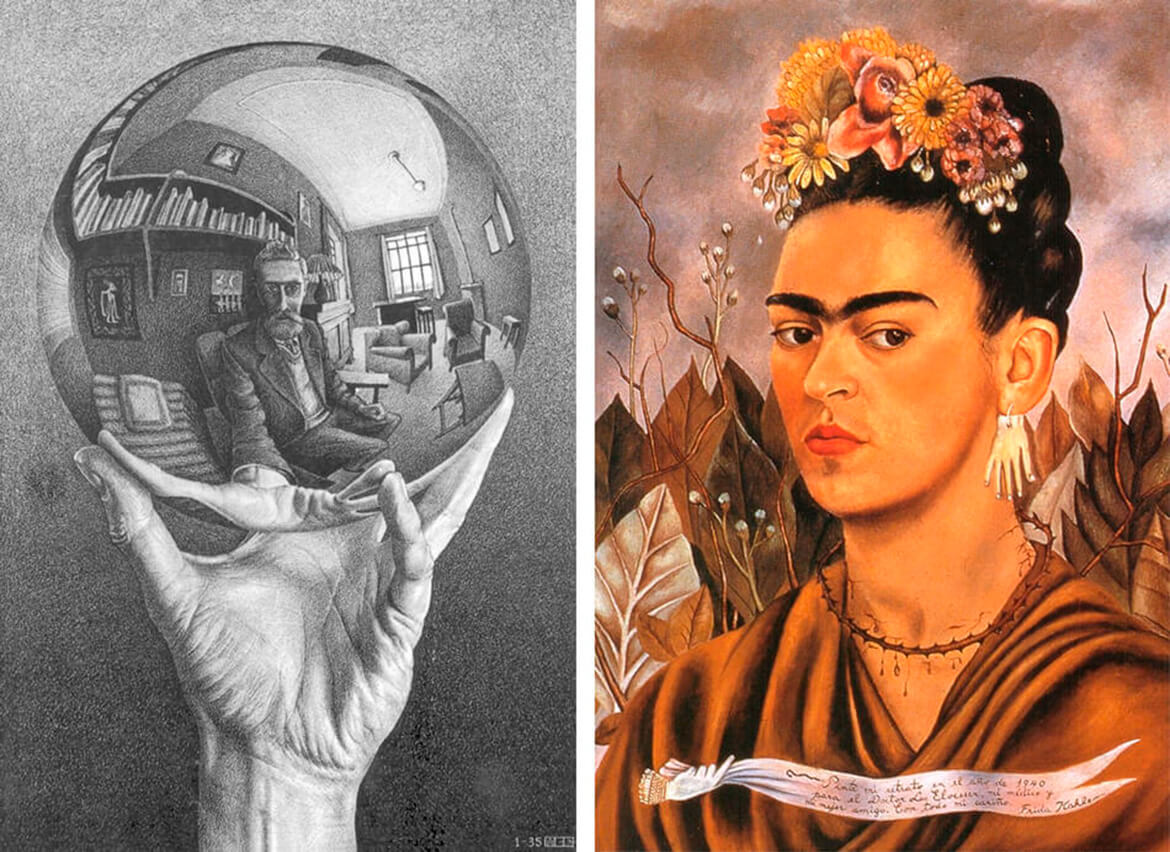

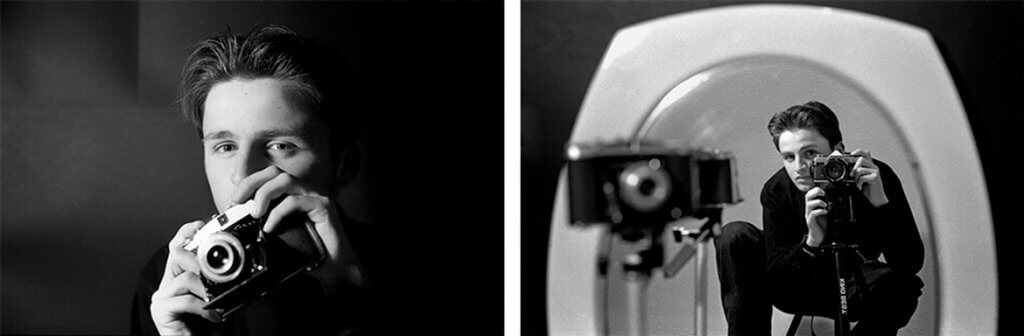

In my case, the self-portrait has always been present in my different photographic stages. From the first black and white ones, which were based on curiosity and the expectation of seeing oneself ‘from the outside’. To those in which, having overcome any innocence, they have ended up forming part of my own personal deconstruction processes in each creative period through which I have passed.

It is in the latter that the representation of oneself is closer to a subjective, and in some cases distorted, recreation than to the image that any encounter with a mirror can give you back.

In fact, the fewest have been self-portraits through a reflection. The most, undoubtedly, with the most widespread system. Thanks to the programmed trigger mechanism of any camera or imaging device, with a timer that allows you, after preparing the scene beforehand, to place yourself inside it and take a self-portrait.

From left to right: Self-portraits 1 and 2 (1991). The distortion of the habitat (2003). Hipnótico (2003) © Bernat Gutiérrez.

Influencers

Accepting then that Robert Cornelius’s photograph is the first photographic self-portrait in history. It must be acknowledged that since then photography has explored and exploited this format as an expressive medium to the point of satiety.

The use of the self-portrait has become an artistic explosion that has earned its own denomination of origin within the amalgam of currents and styles that populate the history of contemporary art.

It is impossible to include them all in this article, but here is a brief selection of photographic works that, due to their idiosyncrasy, form a good collection of the aesthetic, technical and creative possibilities explored through the self-portrait by some of my favourite photographers.

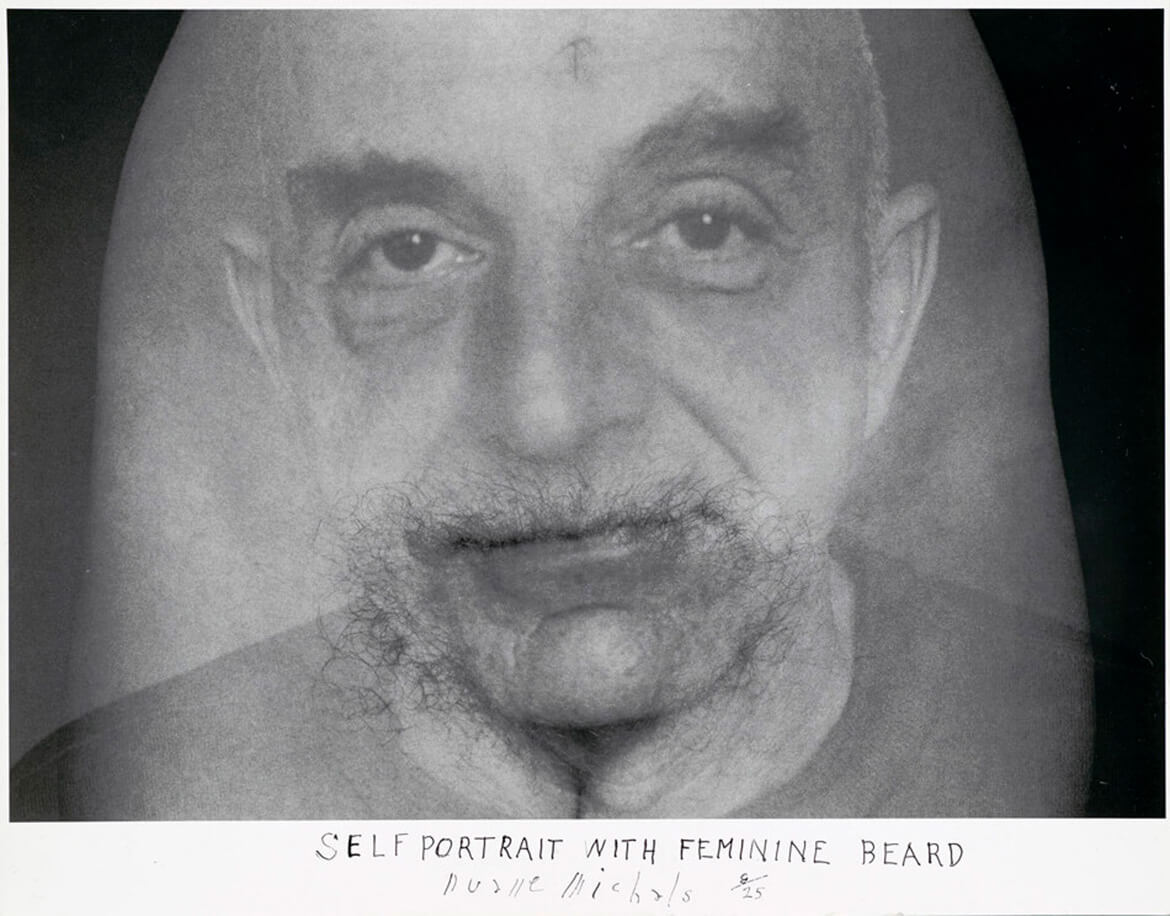

Duane Michals

Duane Michals, to whom I dedicated a large part of my previous article, Things are weird, has some of the funniest and most sarcastic self-portraits I have ever seen. Always with the simplicity and naturalness that characterises his photographic style.

After all, as I have already mentioned in a previous paragraph, the style and technique of any artist is reflected in the self-portraits, almost as much as the figure of the self-portraitist himself. The style and technique of any artist is reflected in self-portraits, almost as much as the figure of the self-portraitist himself.

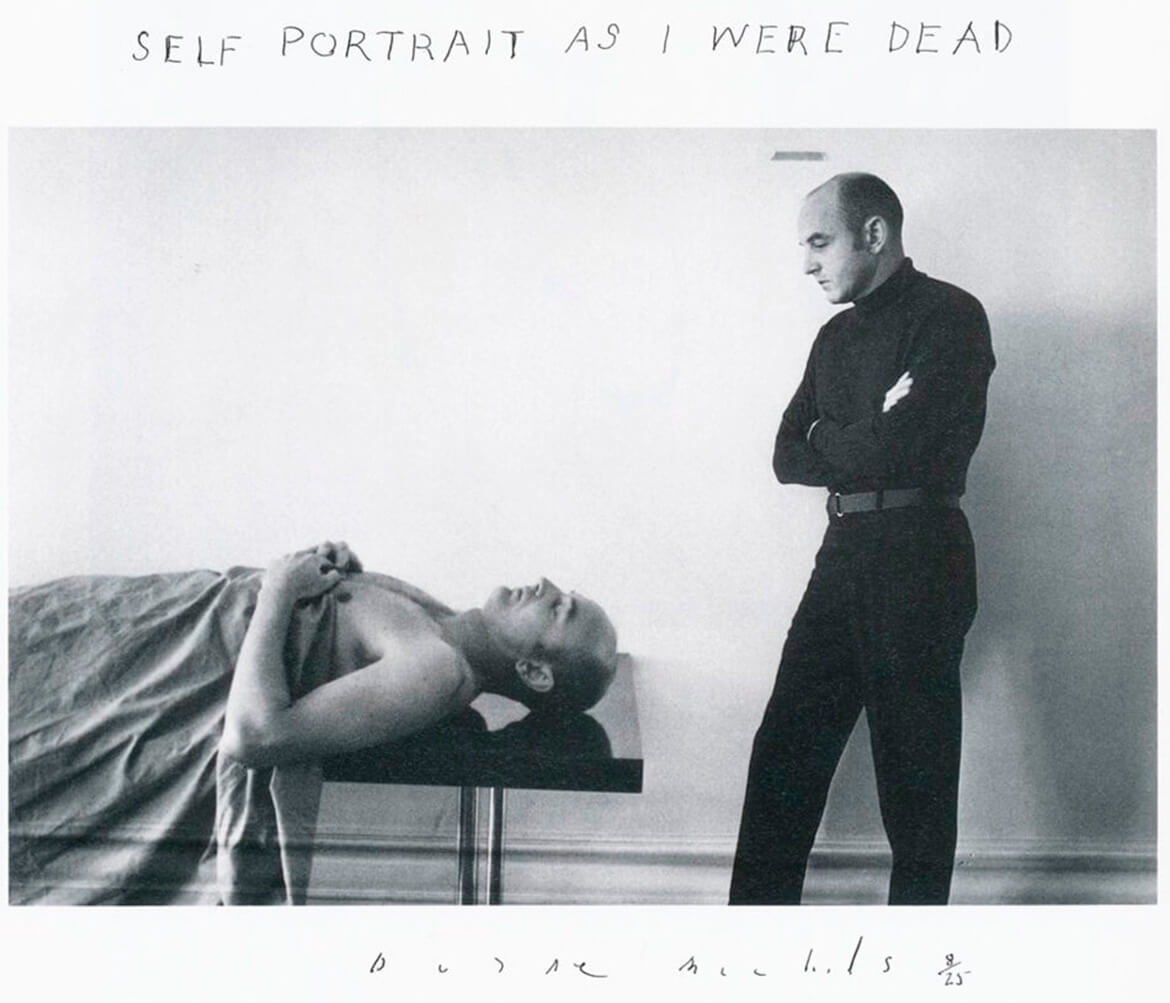

In the case of Michals, the reflections in most of his works are linked to the sense of humour he applies to others. Without stripping them, in any case, of the philosophical and human discourse that characterises his career. And always with that austere style that he imprints on all his images, both technically and scenographically.

Self Portrait With Feminine Beard (1982) and Self Portrait As If I Were Dead (1968) are not only an amusing display of his ingenuity, but also have the particularity that both photos were taken using the double exposure technique, so typical of photography.

Self Portrait With Feminine Beard (Self PortraitWithFeminineBeard, 1982). © Duane Michals.

Self Portrait As If I Were Dead (Self Portrait As If I Were Dead, 1968). © Duane Michals.

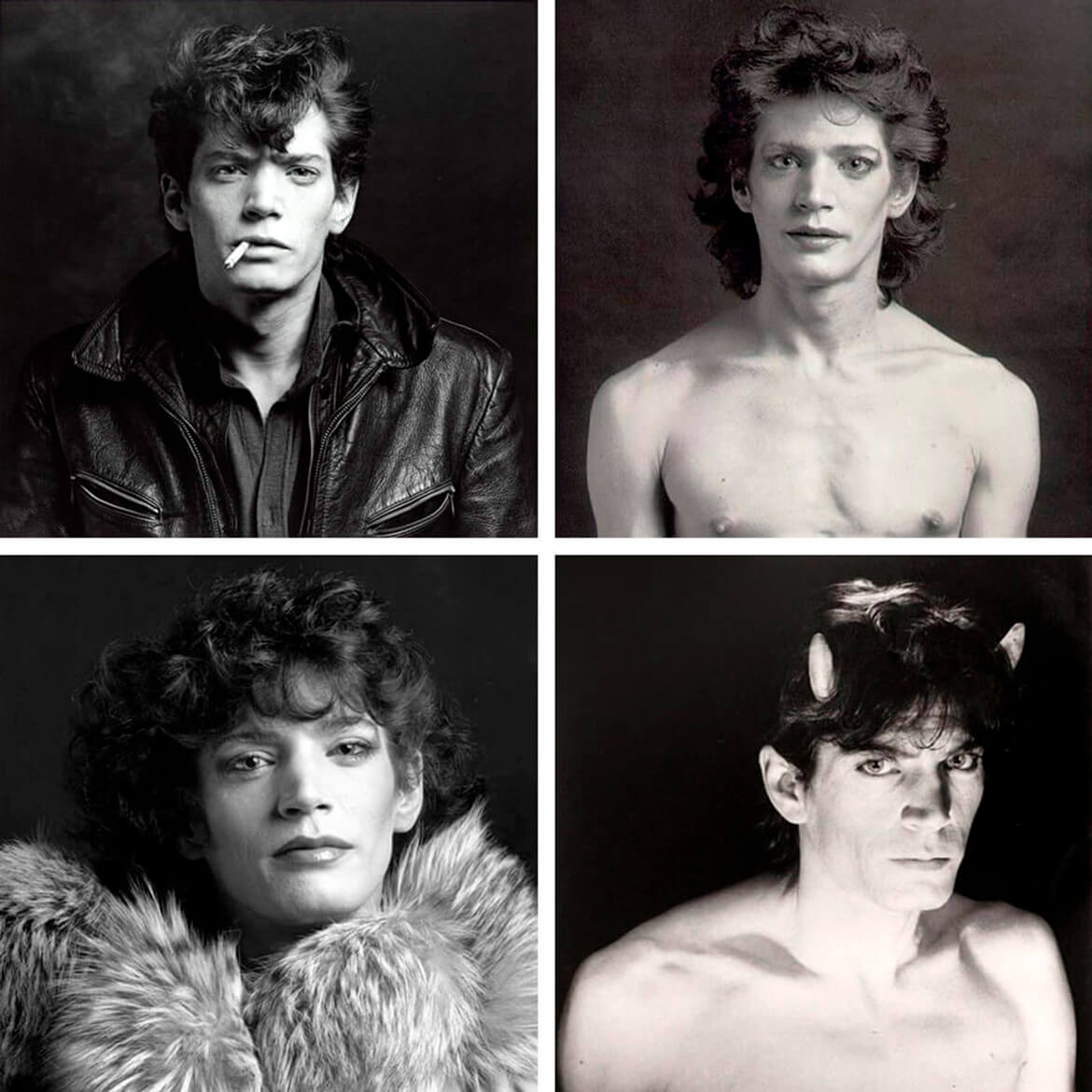

Robert Mapplethorpe

Another example worth knowing is that of the late American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who died in 1989 at the age of just 42. Despite his short career, he has undoubtedly earned his place in the recent history of photography.

Studio portraitist with a classic black and white style, also simple and sober. Celebrities such as Andy Warhol, Richard Gere, Peter Gabriel, Grace Jones, Sigourney Weaver, Isabella Rossellini and Patti Smith (with whom he maintained a complex and profound relationship, beyond their mutual artistic inspiration, until the day of his death) have passed through his camera.

But Robert Mapplethorpe has undoubtedly gone down in posterity for his controversial and explicit erotic portraits, for which he did not hesitate to make use of a visual language more akin to pornography and elements of sadomasochistic culture. Some of his works became important symbols of the LGTB culture of the 1970s and 1980s. Possibly his photographs in this facet would not pass the filter of today’s insufferable political correctness that takes everything out of context and that is not exactly characterised by seeing beyond a span of its enormous nostrils.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits are also an extension of his entire photographic oeuvre. The same simplicity, the same schemes of soft, uniform light on neutral backgrounds as the only backdrop. And, of course, the same ability to show through them, with total transparency, the soul of one of the most relevant photographers in contemporary culture.

Self-portraits. Robert Mapplethorpe.

Erwin Olaf

Another photographer who has explored the possibilities of the self-portrait as a means of artistic expression is the Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf.

I admit that I have a real weakness for Olaf’s work, which we will analyse in detail one day.

Technically sublime, in every aspect, with a style so refined that his images seem like aseptic packaging that repels any imperfection. His visual discourse is pioneering and has set trends that we can see reflected in the work of other interesting active photographers such as Gregory Crewdson or the publicist Jean Yves Lemoigne.

As well as in cinema, by the hand of one of today’s directors with a cinematographic language so stylised that it borders on obsession. I am referring to Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive, Only God Forgives, The Neon Demon).

Erwin Olaf’s images have a clear advertising and commercial code. A character that he not only imprints in his highly reputed professional projects for brands such as BMW, Nintendo or Microsoft. But also in his heterogeneous personal work, which in some aspects is reminiscent of Robert Mapplethorpe’s slender portraits and also of his more transgressive side.

In 1999 he was awarded the Silver Lion at the Cannes Advertising Festival for his photographic work for an international campaign for the Diesel textile brand. His work can currently be seen in publications such as The Sunday, Elle and The New York Times Magazine.

Self-portraits taken between 1985 and 2015. © Erwin Olaf.

Cindy Sherman

We cannot talk about self-portraiture without mentioning the peculiar work of the New York photographer Cindy Sherman. Another totem of modern photography whose images mainly feature an endless succession of versions of herself.

Through these images she channels and raises some of the most burning issues of contemporary society and the role and representation of women in it.

Curiously, Sherman does not consider her photographs to be self-portraits, since, according to her, her representations are characters with an entity of their own. The protagonist is not the author who, although he is the one who is incarnated in the figure depicted, it is the latter who finally acquires the capacity to convey a discourse in a totally autonomous manner.

Cindy Sherman’s recreations are authentic performances. Some of them are tremendously shocking and transgressive. In her transformations what is most surprising is her chameleon-like ability to mutate into her own characterisations, playing with visual codes typical of cinema, theatre, advertising or classical painting. This photographer takes female stereotypes almost to the point of paroxysm precisely in order to pillory them before the very society that has created them.

Self-portraits. © Cindy Sherman.

Beyond the fourth wall

If there is one thing that fascinates me about photography, it is its ability to break its fourth wall and forcefully shake the viewer’s perception, putting him or her in a conjecture about the verisimilitude of what is before his or her eyes.

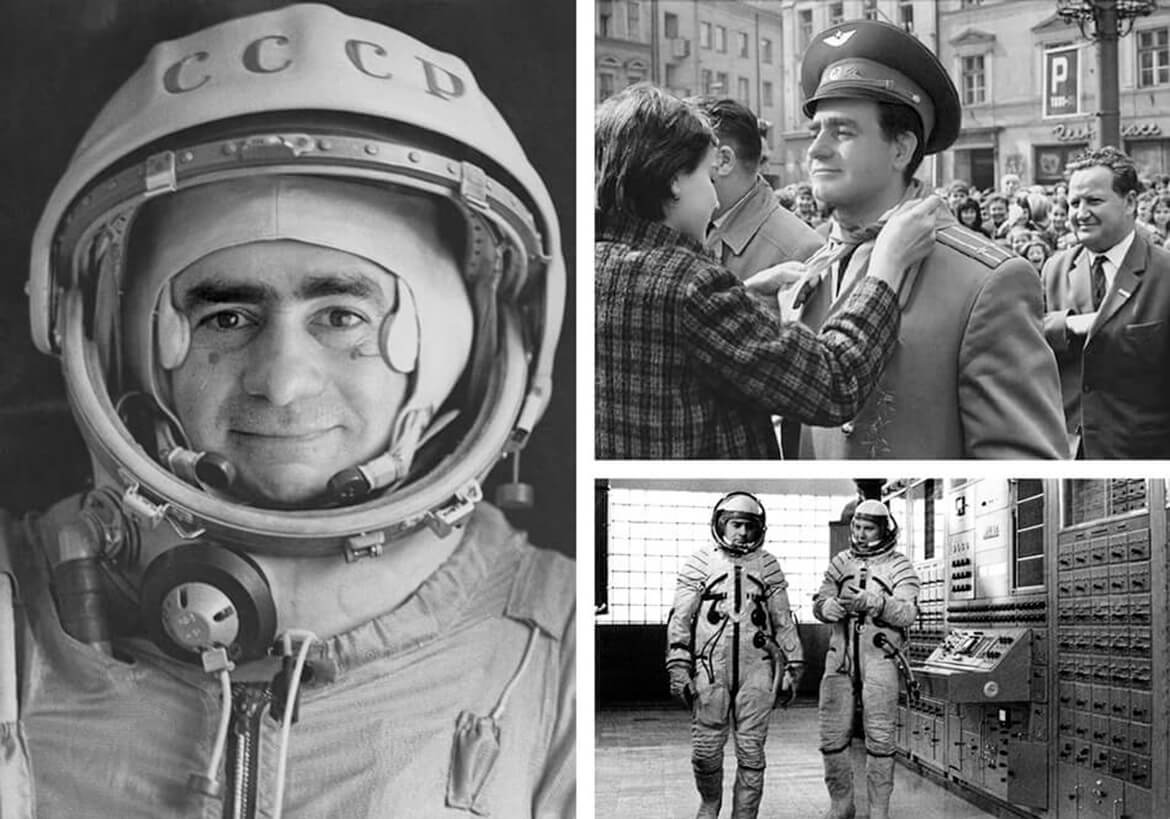

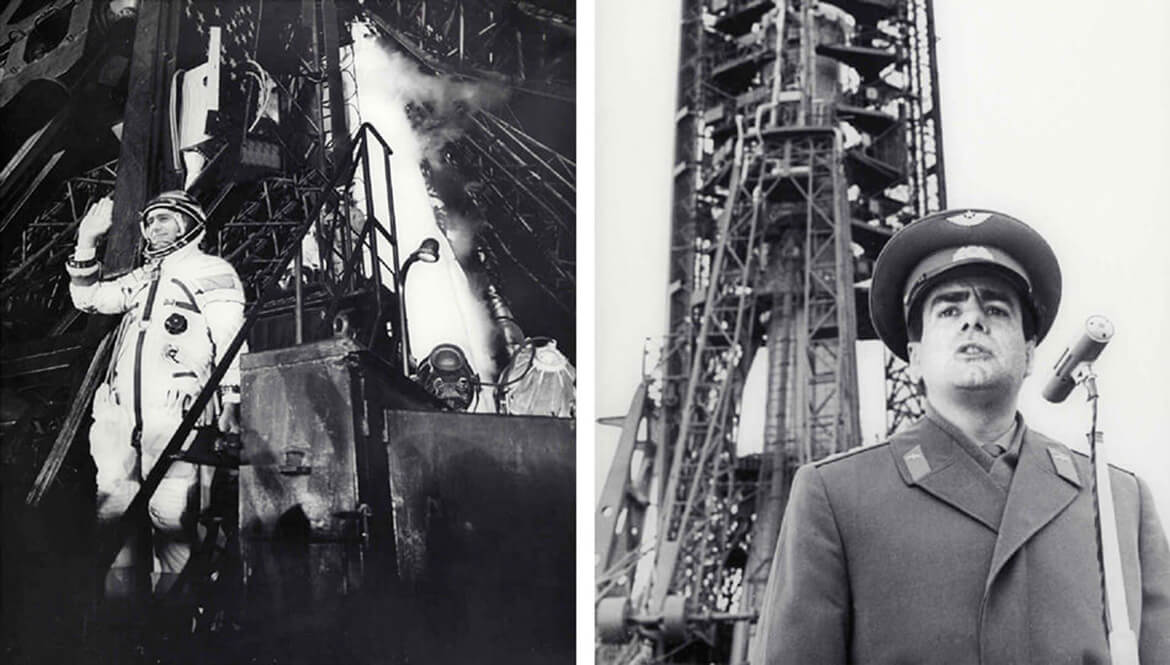

In 2006, the programme Cuarto Milenio, which at the time was broadcast on the TV channel Cuatro, discussed the case of the Russian cosmonaut Ivan Istochnikov. According to presenter Iker Jiménez and the alleged investigator of the case, Gerardo Peláez, he disappeared in 1968 on a space mission aboard Soyuz 2.

After this resounding failure in the USSR’s space race, the Soviet leaders decided to erase any trace of Ivan Istochnikov’s existence and his connection with the Russian space programme. They even went so far as to erase his figure from official photographs of the time.

The Cold War and the competition between the US and the USSR to see which of the two superpowers would conquer space first was in full swing. The fiasco of the Istochnikov cosmonaut mission was something the Russians could not allow to be made public.

According to the programme, the case is uncovered three decades later at a New York auction where a journalist comes into possession of classified material from the former Soviet Union. Among the material is a photograph of this supposed ‘phantom cosmonaut’.

Based on these facts, Jiménez and Peláez (they sound like characters from Mortadelo y Filemón) unravel the true story of the cosmonaut Ivan Istochnikov in the programme with photographs and documentation.

Joan Fontucuberta

So far so good, were it not for the fact that the ‘true story’ of the cosmonaut Ivan Istochnikov was nothing more than the fruit of the imagination of the Catalan photographer and analyst Joan Fontucuberta. A specialist in playing with the supposed veracity of photography and that, on this occasion, to make matters worse, he played the leading role himself, incarnating the ill-fated Istochnikov in a succession of self-portraits manipulated in the format of a journalistic photograph.

Photographs from the Sputnik project (1997). © Joan Fontcuberta.

All this ‘lie’ created by Joan Fontcuberta formed part of the installation Sputnik, which he exhibited at the Fundación Telefónica in 1997. A performance project, made up of photographs, press clippings, supposed reports and classified documentation on the case of Ivan Istocknikov (including the Russian adaptation of the author’s own surname) that the editorial (and research?) team of Cuarto Milenio swallowed whole.

Until recently, the video of the programme in question could be found on Youtube, but Mediaset, citing its rights over the content, has erased any trace of it, in the same way that the USSR erased the story of the phantom cosmonaut Ivan Istocknikov.

Photographs from the Sputnik project (1997). © Joan Fontcuberta.

Bonus Track

I could not close this post without talking about a photographic experiment, which is not only an interesting creative project but also opens up a debate that is well worth another article on the evolution of the techniques and codes of photography in the 21st century.

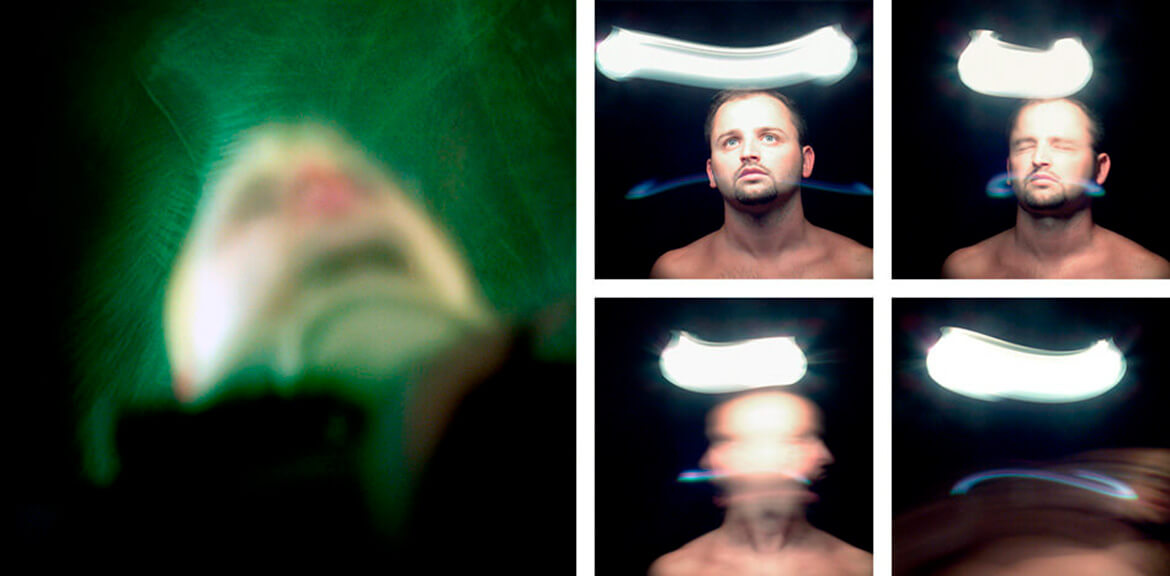

I am referring to the project Diseccionados by the Valencian photographer and teacher Lalo Martínez, who I referred to in my last article when I told you about my own experience as a student of Image and Sound and the change brought about by the arrival of a new teacher who turned the syllabus upside down.

Diseccionados is striking for the representation that Lalo Martínez makes of the different states of human emotions (rage, madness, pleasure, pain, etc…) based on images that show only the faces of those photographed as if they had been carefully separated from the skull and stretched until they were captured, end to end, in a single two-dimensional plane.

Among the pieces in Diseccionados there are some self-portraits, such as the work Pánico.

Panic (2002). © Lalo Martínez.

But to understand to what extent an experimental exercise like Dissected is relevant and to see how photography is reinventing itself in this digital era, it is necessary to understand the process of obtaining these images. Because once again we are faced with a case that implies rethinking some dogma of faith.

The imaging process

The “photographs” of Diseccionados (and this is when I put inverted commas around them) have not been taken by a camera, but by a scanner. The photos have been created from a laborious and complex scanning process in which Lalo Martínez has been turning the faces of his models (and his own) from side to side, in a rotational movement synchronised with the speed of the light beam of this type of device.

And this is where we open another melon on the evolution of the photographic act.

The camera in its different variants and techniques is no longer an exclusive medium for photographic imaging.

That of pressing a button, be it mechanical or digital, gives way to other processes that arise when, through experimentation, other devices and gadgets are stripped of the logical functions for which they were invented and manufactured.

Who said television would kill the radio star?

Arcadina goes with you

Creativity goes with you, offering you the best service goes with us

Fulfil your dreams and develop your professional career with us. We offer you to create a photography website for free for 14 days so that you can try our platform without any commitment of permanence.

Arcadina is much more than a website, it is business solutions for photographers.

If you have any queries, our Customer Service Team is always ready to help you 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. We listen to you.