Things are queer

I remember a review written after a photographic exhibition I did, more than 20 years ago now, in which the author of the exhibition called my images “black and white landscapes”. At that time I was much younger than I am now (xennial optimism) and as disenchantment had not yet hit me hard in the face, I still dreamed that, with time, I would make a respectable place for myself in the photographic Olympus.

It is true that at that time I still photographed exclusively in black and white, and it is also true that most of my photographs were taken outdoors. But I have never had, neither then nor now, any interest in the “realism” of the photographed space, neither at the time of seeing it, nor at the time of capturing it in a photograph. That “black and white landscape photography” thing felt a bit like a kick in the pants, more for the fact of thinking that, perhaps, my photographic style (if there was one back then) might be somewhat undefined, than for a review written by someone who, presumably, hadn’t quite understood what it was all about, probably as a consequence of the former.

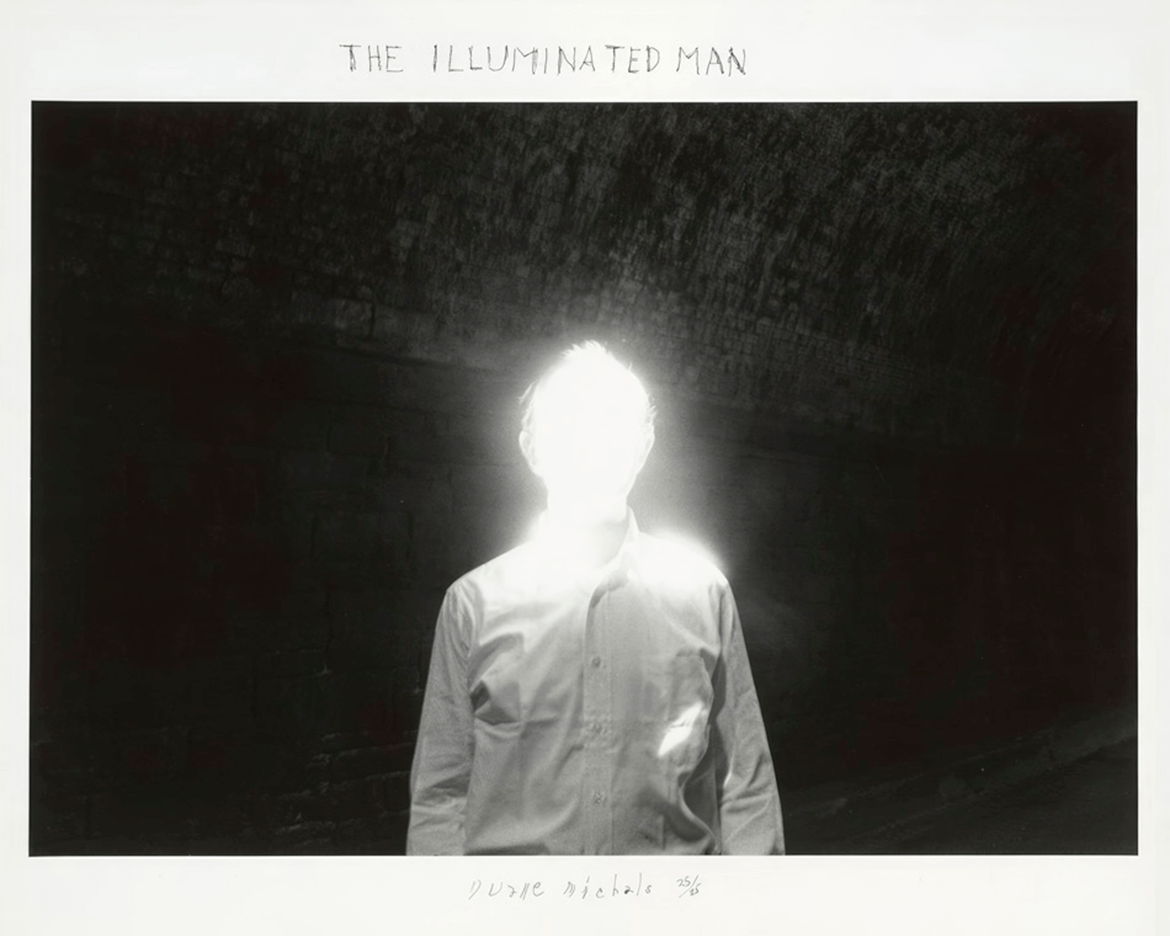

The Illuminated Man. © Duane Michals, 1968

Contenido

The photographs I take

The photographs I take for myself are the antithesis of everything I do in my work. They were before and they are now. When one becomes a multidisciplinary professional it is possibly because one has always had a certain tendency towards eclecticism. In my case, eclecticism is not something exclusive to my professional facet, but I think it came as standard in me from the beginning. In fact, if it hadn’t been for the motorbike crash I described in my previous article and the story that followed, I would probably have opted for music instead of photography.

It is possible that the perceived lack of definition of which I speak in the previous paragraph was the evident reflection of that eclecticism which, in time, was the key to being able to make a living from my work and, what’s more, to enjoy it. I also believe that it was precisely this eclecticism that sentenced my artistic career to anonymity, because there’s nothing that an aspiring artist playing so many different styles in a world in which everything has to be catalogued, pigeonholed, standardised and labelled… “What do you do? “Go that way!” “Well… I’m a performance artist…” “Come on, fuck, that’s something else…!”.

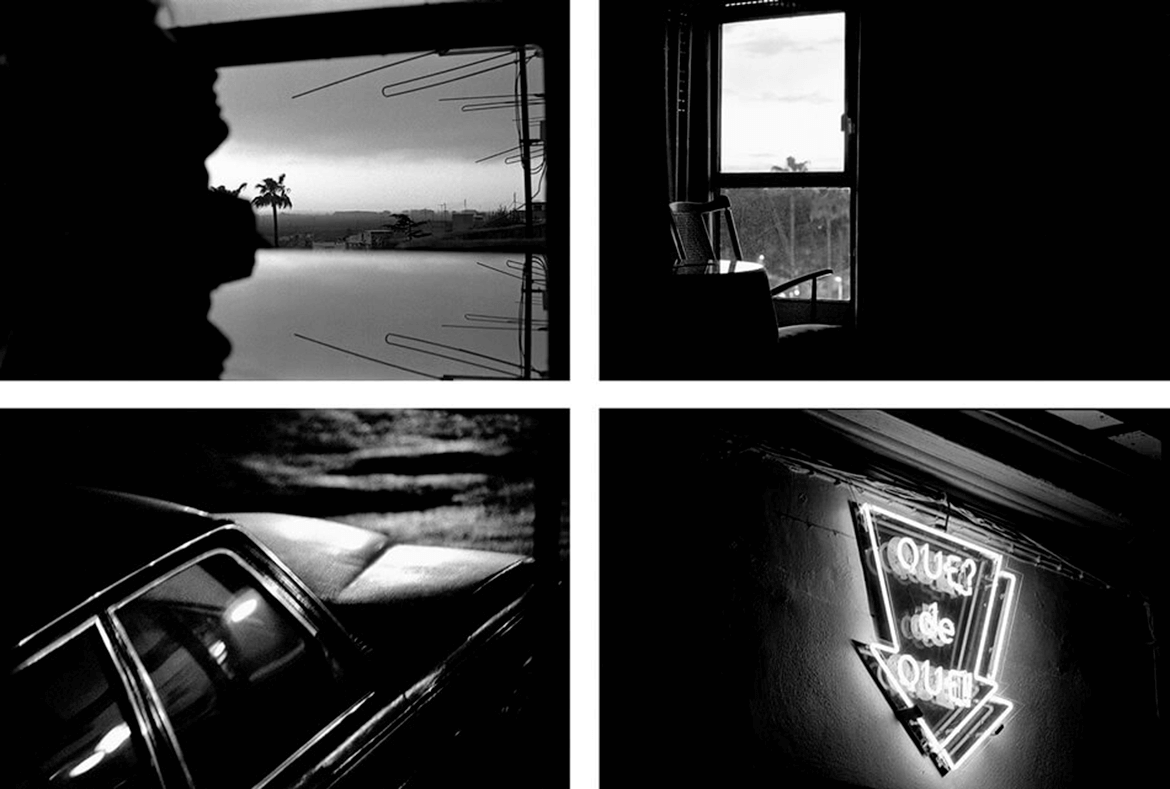

What is clear to me is that when I took the photographs I had no intention of creating a postcard image, but rather of an experimental exercise (which I still don’t know whether consciously) in which the photographed space is reinterpreted and filtered until it becomes a visual fragment stripped, as far as possible, of the attribute of reality.

Black and white” landscape photographs

I have always thought that those “landscape” photographs of my black and white period showed another type of landscape, that which is not seen but which is sensed: the interior landscape, directly linked to the states of mind and emotions, which is filtered to the exterior through a means of expression (photography, writing, sculpture, painting, etc…).

But to go into this area would imply a certain amount of human psychology, or good old-fashioned mandanga, and that is not the crux of the matter in this article. What is clear to me is that when I took the photographs I had no intention of creating a postcard image, but rather of an experimental exercise (which I still don’t know if it was consciously) in which the photographed space is reinterpreted and filtered until it becomes a visual fragment stripped, as far as possible, of the attribute of reality. Again, although I repeat myself like garlic, the subjective act of photographing.

From left to right: La palmera (1991), S/T (1990), S/T (1993), S/T (1991). © Bernat Gutiérrez

It’s all in the books

It is through some books on photography in essay form that I have found the tools to better order and define all these perceptions and questions derived from my interest in understanding photography over all these years.

There are some key ones, such as those written by the photographer and analyst Joan Fontcuberta El beso de Judas. Photography and truth (Gustavo Gili 1997), Pandora’s camera. La fotografía después de la fotografi@ (Gustavo Gili 2013) or La furia de las imágenes. Notas sobre la postfotografía (Galaxia Gutemberg 2016), also Visto y no visto by Peter Burke (Editorial Crítica 2001), La fotografía plástica by Dominique Baqué (Gustavo Gili 2003) and others that, although not exclusive to photographic art, are a perfect complement, and undoubtedly necessary, to better contextualise all this overdose of data and photographic analysis.

The essential Of the Spiritual in the Art of Kandinsky (1952) and that cannelita en rama that is The Praise of the Shadow by Junichiro Tanizaki (1933). But without a doubt, if there is one book that helped me to find a much more suggestive and accurate definition of the photography I did and do for myself, it was Poetics of Space (Gustavo Gili 2002). A compilation of articles and writings on photography and photographed space by the photographer and historian Steve Yates, based on another essential book, La poétique de l’espace by the philosopher Gaston Bachelard.

And now is when you get to that point where, Homer Simpson-like, you say to yourself, I’m bored, the perfect moment to do a kit-kat between the lines and consider a little visual exercise. Take a (good) look at the following sequence of images.

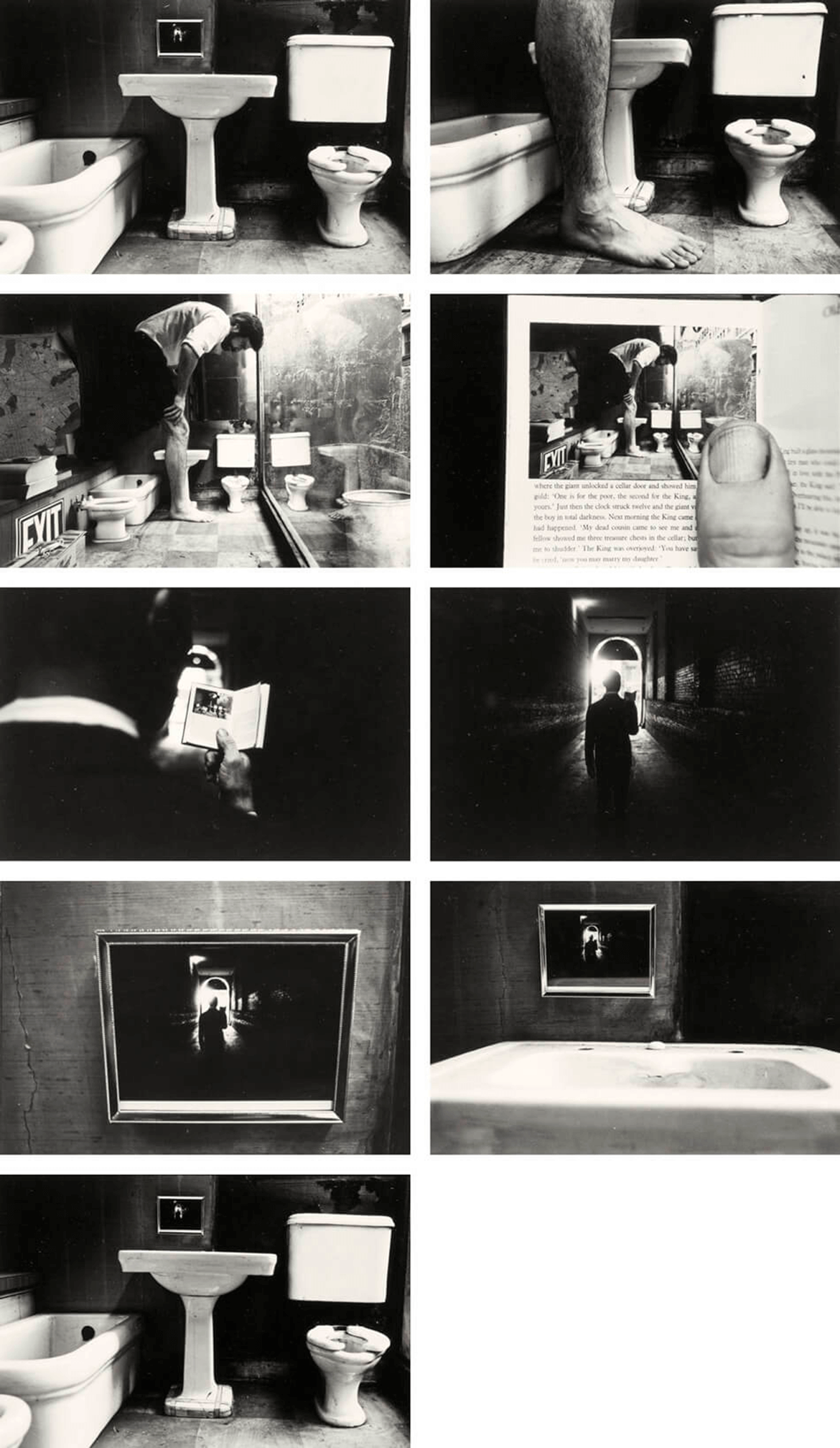

Things Are Queer. © Duane Michals, 1973

Duane Michals’ weird stuff

When I discovered the work of the American photographer Duane Michals (Pennsylvania, USA, 1932) I was a first-time photographer and a student of Image and Sound. Until then, learning photography outside my autodidacticism was limited to those classes in which, beyond the technical aspects, such as the use of a camera or the process of developing and chemical printing, we went into the basic concepts of fashion photography, advertising, press, etc…

Everything is very ready to turn us into workers rather than creatives. It is 1993.

But then along comes a young teacher, with the enthusiasm and vigour of someone who has not yet been hit in the face by discontent (sound familiar?), and he turns the syllabus upside down, no longer treating his students as mere aspirants to a degree, but instead encouraging critical thinking, creativity and the ability to overcome when tackling any photographic exercise.

And it is thanks to him that we discovered the work of Robert Mapplethorpe, Jan Saudek, Sandy Skoglund, Cindy Sherman, Joel Peter Witkin, Cristina García Rodero, Ouka Lele… and, in my case, straight to the potato like a missile: Duane Michals.

During the fifties and sixties of the last century, photographic excellence continued to be marked by documentary photography as a “reliable” representation of reality, captured at the “decisive instant”.

Not that there wasn‘t already, at that time, a more plastic or artistic photography, so to speak, but at a time when the photographic act was still linked to capturing the real moment at the right moment, the Olympus of photography was made up of names like Robert Capa, Robert Frank, Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson or the sacrosanct Magnum Agency.

The first photographs of Duane Michals

Duane Michals’ first known photographs date from 1958. A series of black-and-white street portraits taken during a trip to Russia which, although they could be included in the street photography that was already in vogue in those years, already showed the simplicity and naturalness that were to characterise his photographic style.

Even when it comes to visually representing the most complex aspects of the human condition (life, morality, sex, death…).

The Human Condition. Duane Michals, 1969

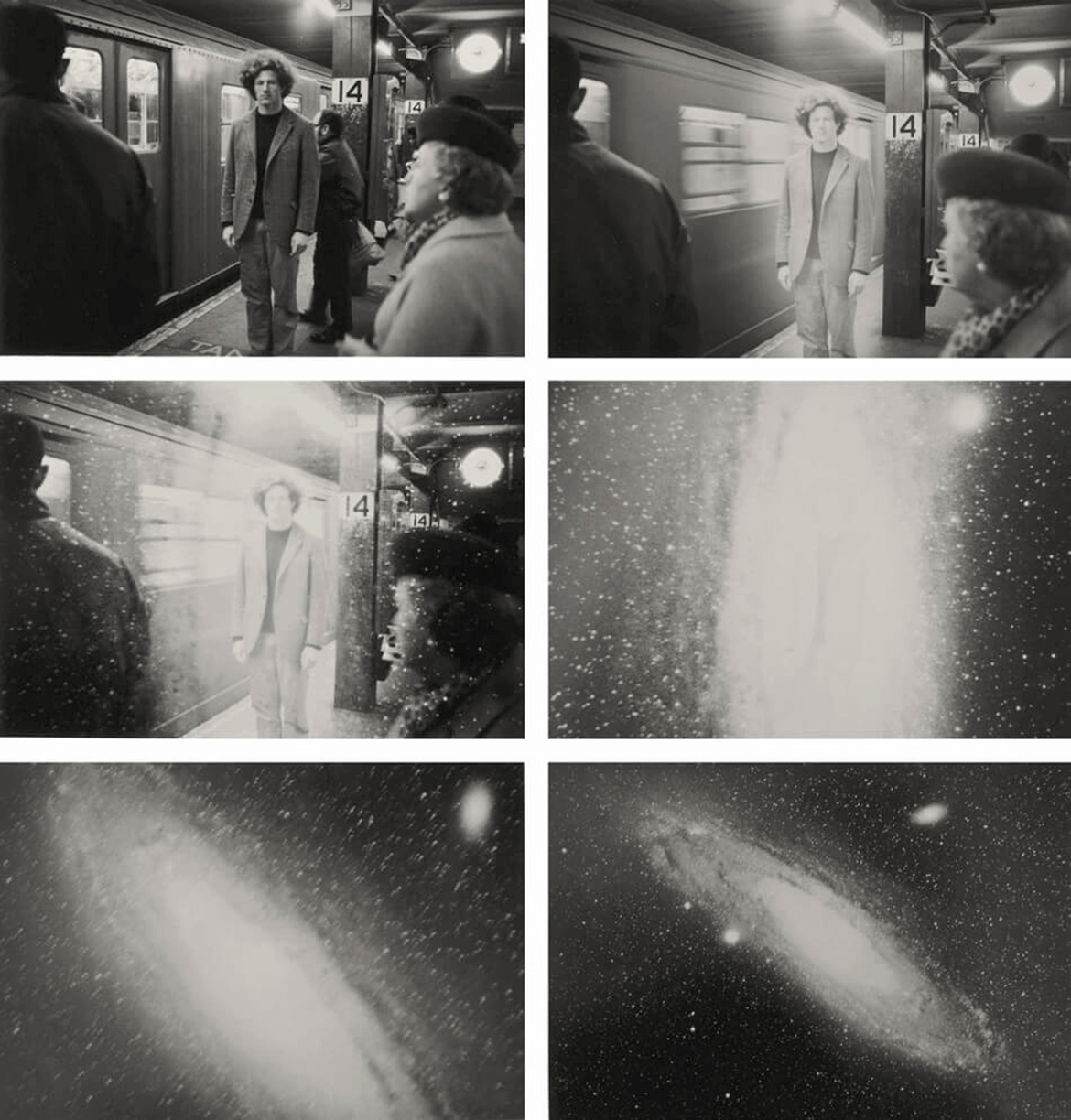

It was from the 1960s onwards that Duane Michals’ photography clearly broke with the established moulds and with the hegemony of documentary photography. Photography as a creative medium capable, not of showing reality, but of photographing that which is not seen.

Duane Michals’ photo sequences

This is where his first photo-sequences were born. This technique would end up being the most representative hallmark of a photographic style with clear influences of surrealism. Undoubtedly the fruit of his meeting and relationship with the painter René Magritte. But with a naturalness and a visual poetry (also written on the photographs themselves) that dispenses with practically all artifice. Making accessible to everyone’s understanding a way of photographing that is close to the conceptual and philosophical, without renouncing a splendid sense of humour.

Although it seems that this “understanding” did not quite take hold in the minds of some of the sacred cows of photography at the time. The anecdote of the American photographer Garry Winogrand, a pioneer of street photography, is well known. In 1963, after seeing Michals’ first exhibition in a gallery, he left the gallery in a huff, shouting “That’s not photography”.

The anecdote of the American photographer Garry Winogrand, a pioneer of street photography, is well known. In 1963, after seeing Michals’ first exhibition in a gallery, he left the gallery in a huff, shouting “That’s not photography”.

The Things Are Queer sequence

It is with the famous sequence Things Are Queer (1973), which opens this section, that Duane Michals blows up any realistic conception of the photographed space.

Nothing is what it seems. Each photograph in the series reveals the lie of the previous one and involves us in the resolution of a visual puzzle made up of 9 images that always leads us to the same starting point, or end, depending on how each one looks at it.

A fascinating imaginary (and imaginative) loop that tests, from the most overwhelming aesthetic simplicity, the viewer’s perception and interpretation of truth. Photography as reliable and accurate proof of reality? But what reality? What truth?

Chema Madoz, the extraordinary in the ordinary

I discovered the photographs of Chema Madoz a long time after those of Duane Michals, and once again I felt again that sensation of maximum empathy and connection with the creative work of an author, which only occurs on rare occasions.

The irrefutable proof, in my case, that something really hits me in the head, is that afterwards I can’t stop thinking about it and, in a way, it ends up becoming a stimulus for my creativity, so often dormant.

It’s not only with photography. With books, cinema and music I also have emotional connections with certain authors, directors and composers. But in the case of photography, without intending to, there seems to be something more selective when it comes to choosing my totems, which, as a general rule, tend to coincide with a certain simplicity and visual austerity but not for that reason lacking in creative complexity.

Seeing with a photographic eye

In the case of Michals and Madoz, seeing with a “photographic eye” borders on the privilege of having a gift.

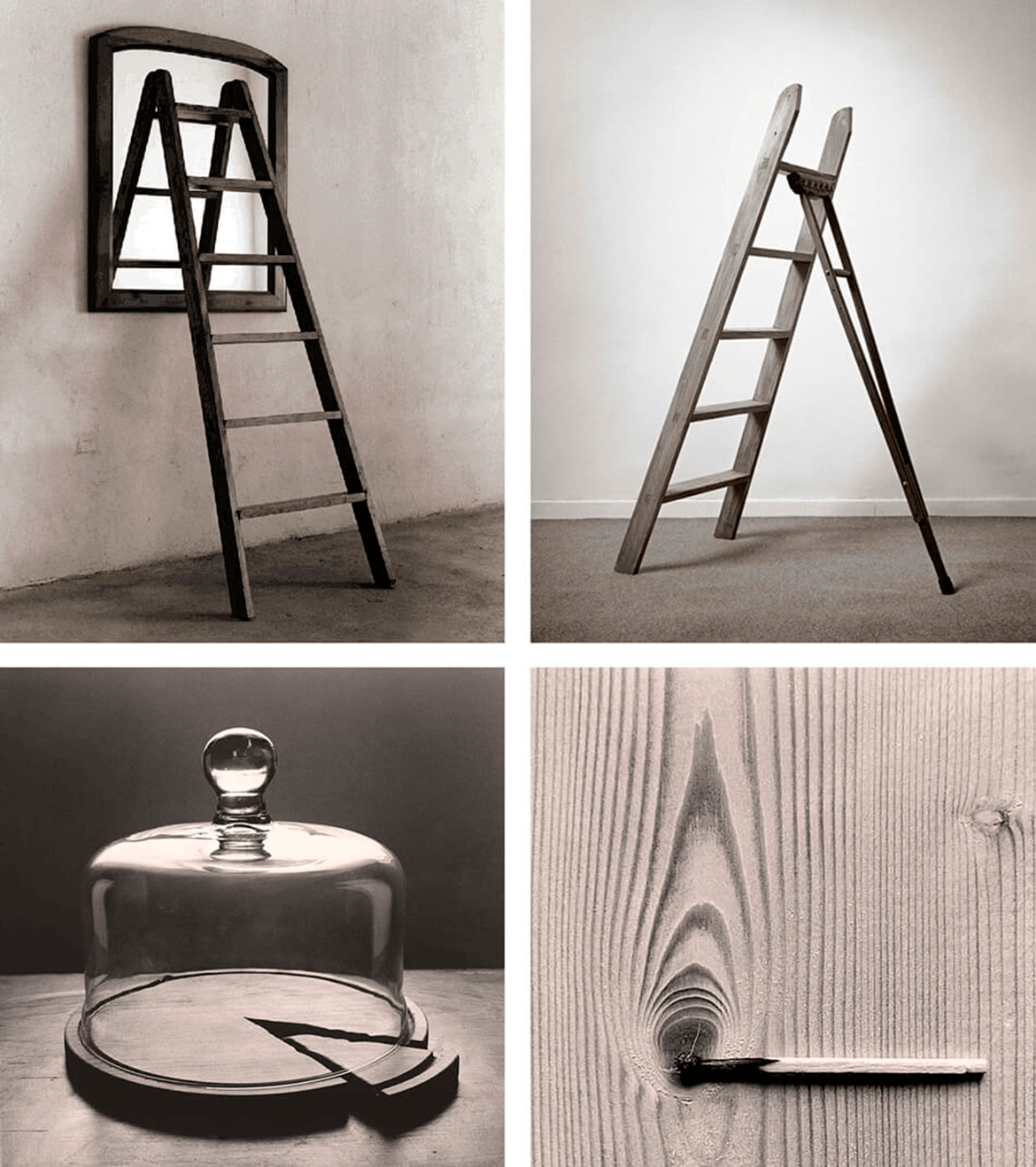

Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) began working with the human figure, but it was not until the 1990s that he developed the visual character that has marked his photographic career, in which everyday objects transcend. Not only their condition as simple inert things, but also the function for which they were created. Although this often has a certain connection or parallelism with Madoz’s reinvention of them.

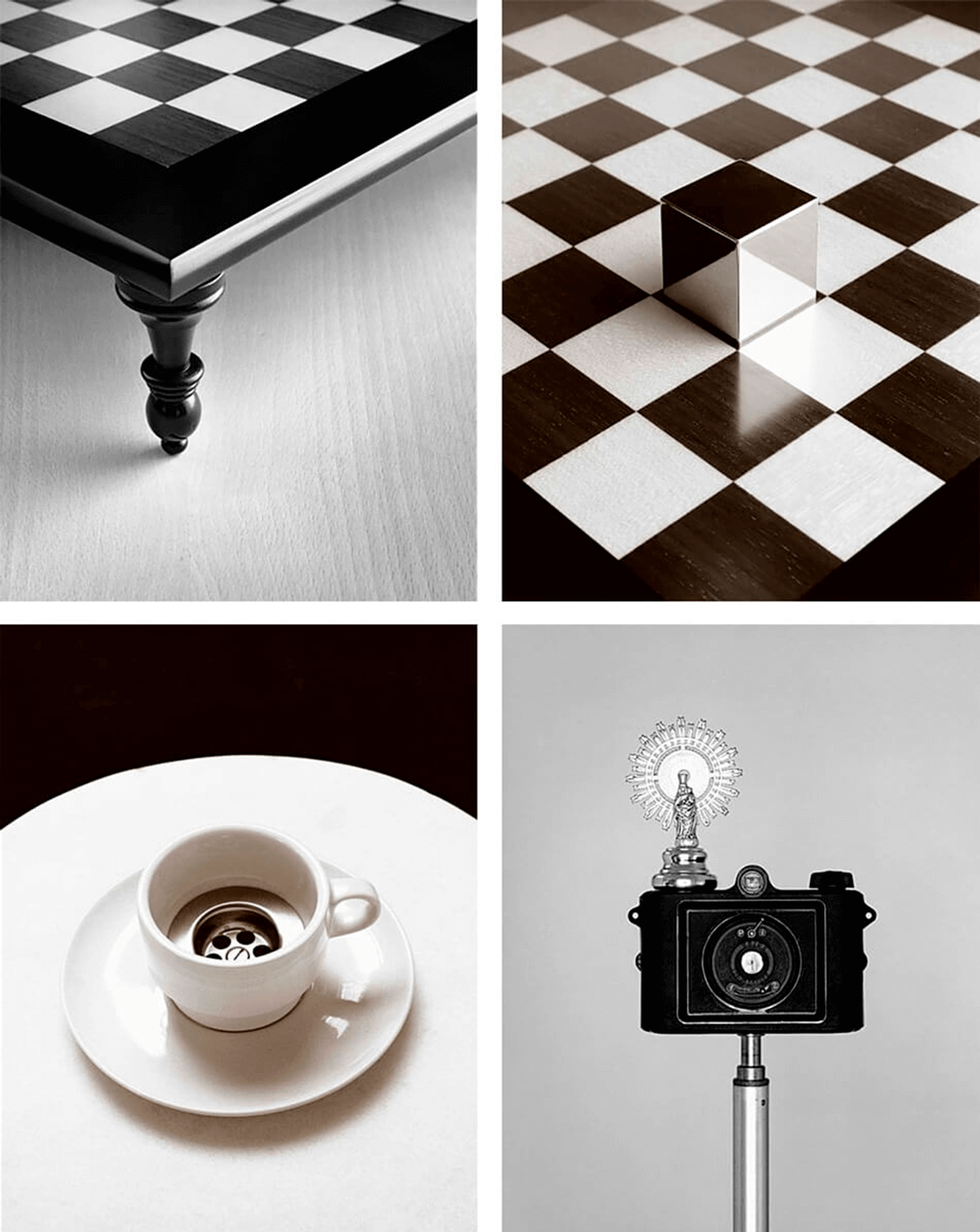

© Chema Madoz

Chema Madoz’s visual conception is even more austere and minimalist than that of Duane Michals. Something that I personally find a fascinating challenge and not at all easy to achieve, given the results.

If in the case of Duane Michals, this austerity is marked by simplicity, both in the translation into images of a more or less complex idea, and by the naturalness of the final framing and the simplicity of the photographic techniques used. In the case of Chema Madoz, it is pure and hard minimalism in which the (new) photographed object is the only protagonist element and there is nothing secondary beyond it and its (new) function that detracts the slightest bit of attention from it. In fact, there is nothing else in the frame. And I tell you, because it is something I have also aspired to achieve in my more personal projects, that to reach this degree of simplicity, both in the content and in what is communicated or transmitted, without any pretentiousness or artifice, is something that goes far beyond being, simply, a photographer.

Photography metamorphoses reality

Photography metamorphoses reality and therein lies its greatness and its deception. It is credible and accessible because it is what comes closest to our perception of reality. It is not a painting, it is not a sculpture, it is not a drawing… It is the “proof” that what it shows exists, even if it does not…

Do Chema Madoz’s objects exist? Yes, they exist, because none of them have been created using digital 3D moulding techniques. They are there or have been created by hand to be there, in this image… But does reality exist as Chema Madoz shows it to us through these objects and their function? It is from here that the photographed space becomes an enigma to be solved by the spectator himself… those interested, of course, in discovering the “1000 words” that lie behind an image… Those who are not, may remain happy and calm in their own inopia.

© Chema Madoz

For practical purposes

Going back to my own experiences, I stopped working in black and white many years ago. My immersion in graphic design led me to (re)discover colour and since then I find it quite difficult to conceive an image without it. It’s as if I were missing a part of the visual information that I didn’t need before. I had a stage in which I used to look using the Zone System and now I do it with a pantograph.

I had a period when I used to watch using the Zone System and now I watch using a pantograph.

Also the processes (and processing) then and now have changed a lot. In the past, the decision to shoot in black and white or colour was made at the first step, when choosing the film, because once you passed that line there was no turning back.

Now, the decision may ultimately be taken when the image has already been captured with a digital sensor which, as a rule, is not monochrome, and previously processed in colour. Even if the final result in black and white is so good as not to give away the origin, in my case, maniac that one is, I find this conversion a bit treacherous and it doesn’t make any sense if you haven’t fully enjoyed a processing conceived from the beginning in black and white.

Perhaps this comes as a bit of a shock coming from someone who philosophises so much about photographic “lying”, but it is one thing to “lie” to you, as viewers, and quite another to “lie” to myself by ignoring my, rather than my principles, experiences with photographic processes.

Keeping the essence

However, it seems that no matter how varied one’s journey through life has been, there are certain essences that are maintained and become noticeable, especially in those moments that arise with the naturalness of something that is not entirely premeditated.

In my case, there is a clear connection with the photographs of some of my current projects with that stage of “black and white landscaping” (in the end I will accept octopus as a companion animal). I still shy away from any postcard image and I don’t give a damn about the reality itself.

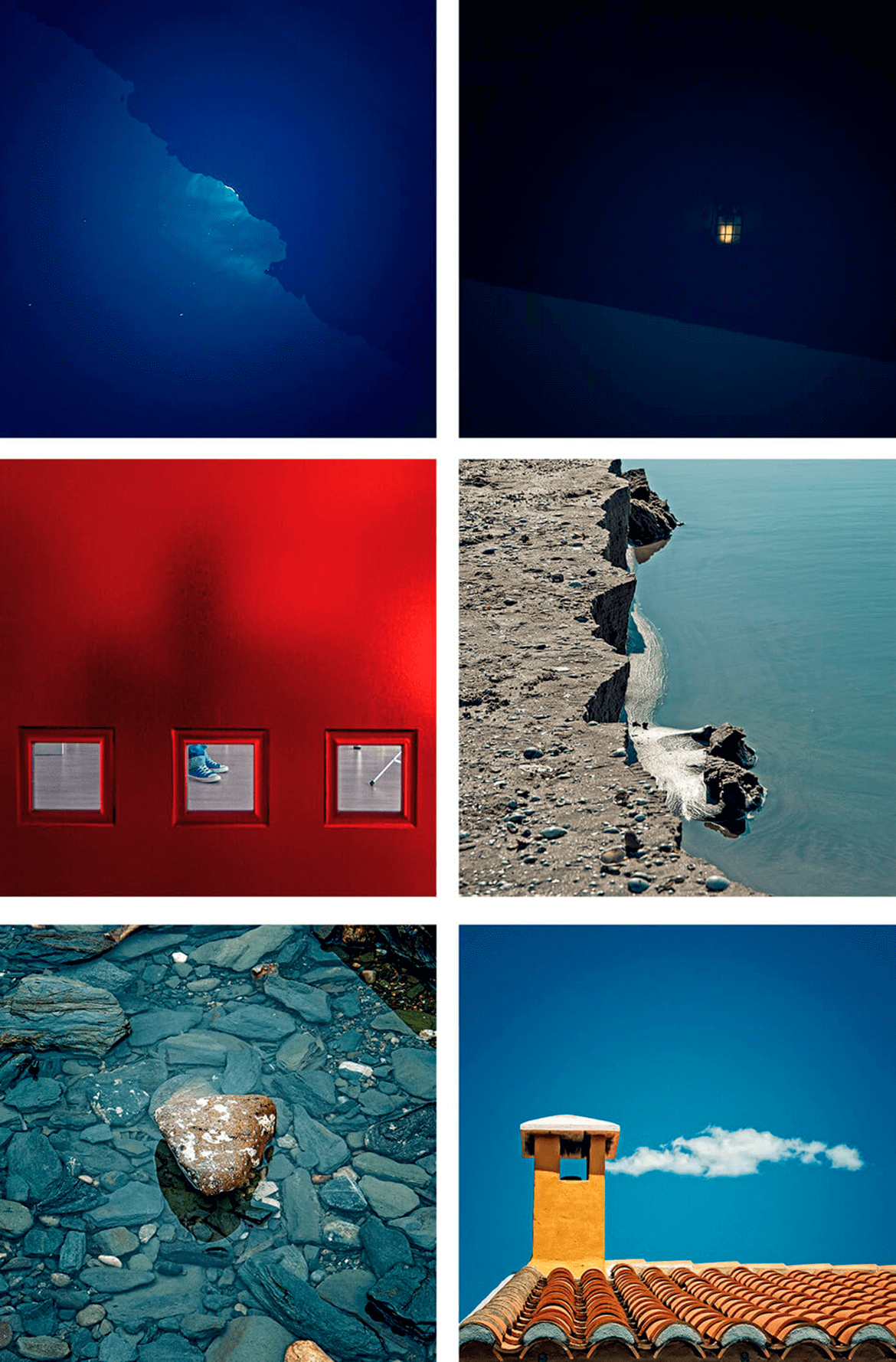

Now, moreover, I succumb to the obsession to minimise the space photographed, to the point of shooting or reframing my photographs in square format, discarding everything that I have too much of.

From left to right: Luz líquida (2013), S/T (2014), Quién te espera al otro lado (2015), Acantilados en miniatura (2008), La isla mínima (2013), Los ojos con los que miras (2014). © Bernat Gutiérrez

The photographer in me

Nowadays, in the midst of all this current technological Big Bang, I find the greatest pleasure in photography when I strip myself of everything that comes with being a multidisciplinary “I don’t know what” and I am left only with the photographer inside me. The one who observes and captures interested fragments of what he sees, immersing himself in his particular exploration of the poetics of space, freed from any previous visual preconception.

Simply letting oneself be carried away by that which flows inside (what makes us creative beings) and which we hardly understand. So much so that, many times, when you look at the photographs that emerge from that state, you are surprised by the result because you don’t quite know what mechanisms have been activated in your brain to get there.

I read on the back cover of the book Poetics of Space “the choice between representing space or dismantling the viewer’s understanding of it is an essential element of modern art”.

What’s more, it’s a fascinating game, as the works of Duane Michals and Chema Madoz demonstrate. And in my case, from the position of someone who is comfortable in a continuous learning process (the teachers are others), it is the way to exercise and test that ‘photographic eye’ which is, after all, the difference between taking photos and being a photographer.

I also read a poem by the Valencian writer Josep Franco:

If you try to touch

the real world

you will never be able to put

a saying to the sky.

(If you try to touch the real world you will never be able to put a finger in the sky).

I leave it there.

* This text accompanies the photographs by Valencian photographer Francesc Vera published in the WALZ catalogue.

Music for this post:

Arcadina goes with you

Fulfil your dreams and develop your career with us. We offer you to try our web service free for 14 days. And with no commitment of permanence.

Arcadina is much more than a website, it is business solutions for photographers.

If you have any queries, our Customer Service Team is always ready to help you 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. We listen to you.